SEOUL —

When Lee Jae-ik started on his path to Shohei Ohtani superfandom, his wife thought he was having a midlife crisis.

Maybe it was that her husband, a 48-year-old radio producer and on-air host at one of South Korea’s biggest broadcasters, had liquidated hundreds of thousands of dollars in stocks to turn his closet into a shrine to the Japanese baseball phenom.

Or that Lee, a high-achieving personality who is so protective of his time that his phone instructs callers to “just state your business,” was suddenly spending his hours after work buried in what he called “Ohtani study.”

In truth, according to Lee, his new obsession was more of an epiphany — one that led him to the airport Friday before dawn alongside the 40 or so members of the Ohtani fan club he founded.

Their aim was simple: to glimpse — and hopefully be glimpsed by — their north star, who late last year signed a $700-million deal with the Dodgers and now was coming to Seoul to play a two-game series against the Padres to start the 2024 Major League Baseball season.

Lee Jae-ik, president of the Ohtani fan club in South Korea, during an interview at home in Seoul.

(Jean Chung / For The Times)

By 2 p.m., shortly before the Dodgers were expected to land, the crowd on the arrivals floor of Incheon International Airport had grown to about 300 people. Television crews swarmed.

Lee waited behind a banner his club had prepared: a massive ribbon of blue and white featuring Ohtani in his new uniform.

“Ohtani is going to know about us after today,” Lee said. “I’m sure of it.”

: :

It all started in 2015 with an international baseball tournament known as the Premier 12. Ohtani, then 21, was mostly unknown outside dedicated baseball circles.

A casual fan, Lee had tuned in only because South Korea was playing. Commentators said that the young pitcher, whose cherubic good looks caught Lee’s eye, was becoming a sensation in Japan.

“Good luck,” Lee remembered thinking. “Too bad you don’t play baseball with your face.”

What followed was a beatdown. In the 13 innings Ohtani pitched for Japan over two matchups with South Korea, he struck out 21 batters and allowed just three hits.

Frozen by the 100-mph fastballs Ohtani was hurling at them, one South Korean batter reportedly returned to the dugout after being struck out and told a teammate: “This isn’t right. You just can’t hit it.”

Impressed, Lee began keeping an eye on his career.

In Japan, where Ohtani played for the Hokkaido Nippon-Ham Fighters, he had been making a name for himself as a two-way wonderboy, defying conventional wisdom that it was impossible for players to excel at both hitting and pitching in modern professional baseball. But could he do it in the most competitive league in the world?

Ohtani’s promising MLB debut with the Los Angeles Angels in 2018, in which he won American League rookie of the year, was followed by two seasons of disappointing offensive production and injuries that shut down his pitching.

Then-Angel Shohei Ohtani talks to reporters in Japan in October 2022.

(Koji Ueda / Associated Press)

Lee prophesized, on an online sports forum, that Ohtani was going to end up a “neither-way player.”

Then in 2021, with 46 home runs and 156 strikeouts, Ohtani recorded what some regard as the greatest season the sport has ever seen, earning him his first American League MVP award and comparisons to Babe Ruth.

Lee was hooked.

: :

In the late 1990s, Lee was a young writer in Seoul blessed with early success, including an award-winning debut novel at 22. He entered a screenplay competition in 2001, winning that too.

At a mixer after the awards ceremony, Lee met one of the judges, a then-unknown film director named Bong Joon-ho. The director, who had been scouting some mountains for his upcoming movie, wore a soiled safari jacket and smelled of sweat.

He personified all the apprehensions that Lee had been feeling about his dream of a writing career. Lee wanted wealth and stability, not to scrabble around in obscurity hoping to beat impossibly long odds. And so when the opportunity to join the broadcaster SBS came along, he took it. Writing would be a sideline.

Angels pitcher Shoehei Ohtani throws a pitch against the A’s at Anaheim Stadium.

(Los Angeles Times)

A few years later, the film Bong had been making, “Memories of a Murder,” came out to great acclaim, leading to a career that included the Oscar-winning 2019 film “Parasite.”

Lee watched the film loathing himself for having been blind to such great talent. Still, he pressed on, becoming the host of a popular current affairs program. His life became a picture of upper-class success: nice cars, modern art, a ritzy apartment with a lofty view of Seoul’s Han River.

But doubts about the path he had chosen deepened into existential shame.

“I was always setting achievable goals so I could reap their rewards — the kind of person parents want their children to be: quick to attain success and averse to failure,” Lee said. “But I’d constantly ask myself, ‘Why am I so shrewd? Why am I so craven? Why do I always compromise with myself?’”

He thought about that when he started watching Ohtani. It reminded him that pure, unbending clarity of purpose existed, just not in himself.

In signing with the Angels in 2017, Ohtani had in effect forfeited around $200 million in potential earnings due to rules that limited international prospects under the age of 25 to league minimum salaries — all so he could test his mettle in the majors that much faster. And even though two-way play would continue to strain his body in ways that his injuries were already showing, Ohtani had held fast.

Lee Jae-ik goes through his baseball cards in the room he calls “the museum.”

(Jean Chung / For The Times)

“Once Ohtani came into my life, I surrendered to this feeling, sort of in the way you would a religion,” Lee said. “I felt at ease. I could just go on with my life, accepting that I wasn’t made for that. I could be content just rooting for Ohtani and the great things he is achieving.”

: :

After Ohtani’s stunning 2021 season, Lee made a vow to himself that he would study, record and collect the many elements of Ohtani’s life. The effort so far has cost him around $380,000.

Deokjil — a term for fervent displays of passion for a hobby or celebrity — offered a welcome escape.

His son had gone off to college, leaving behind stretches of emptiness once filled with rides to school. At work, Lee was kicked off his current affairs show after a song he played triggered accusations of partisan politicking during a tense election year.

His sneakers are now New Balance, his suits Hugo Boss — both Ohtani sponsors.

After seeing Ohtani modeling a Porsche Taycan, Lee bought one in the same color. When he realized Ohtani’s day-to-day vehicle was a Porsche Cayenne, he bought one of those too. Then he started taking the bus to work — where he remained a producer and host of a music program — so he could watch Ohtani videos on his phone during his commute.

Of the 300 or so collectibles, which include jerseys, signed balls, Japanese magazines and reams of baseball cards, Lee’s favorite is an autographed 2018 rookie card featuring Ohtani in red splashed against a chrome blue background, now worth around $20,000.

“There is something very majestic about this one,” Lee said. “His gaze is looking far into the distance, like he’s about to leap forward.”

He wrote a book about his conversion to Ohtani fandom, selling around 3,000 copies.

“I used to mostly write novels, but now that time has been halved,” he said. “All my time and passion shifted over.”

: :

There is a well-known sports adage in South Korea that goes: “We can’t lose to Japan, even in a game of rock, paper, scissors.” It is a nod to unresolved animus over Japan’s colonization of Korea from 1910 to 1945.

In the summer of 2022, as Lee debated whether to start an Ohtani fan club, tensions between the two countries were particularly high amid fallout from a South Korean Supreme Court ruling that Japanese companies should compensate victims of wartime forced labor. Japan launched a trade war, and South Korean consumers responded with a boycott of Japanese goods.

In online sports communities, Ohtani was frequently the target of anti-Japanese sentiment. Lee decided to form his club anyway. He called it Shotime Korea.

Soon Lee began to notice a tone shift when it came to the superstar.

After last year’s World Baseball Classic, Ohtani said he hoped Japan’s victory would lift up baseball in Taiwan, China and South Korea too, affirming what many like Lee saw when they watched him: The most sensational Asian athlete the world had ever seen transcended nationality and dominated the most American of sports in a way that kicked aside the usual racial stereotypes — workhorse, technician, genetic anomaly.

“It’s nothing that we’ve seen before,” said Daniel Kim, a South Korea-based baseball commentator for ESPN and a former scout for the Cleveland Guardians. “He’s got very loyal fans here in Korea and that usually doesn’t happen with a Japanese athlete, so it’s very refreshing to see.”

The fan club slowly grew.

1

2

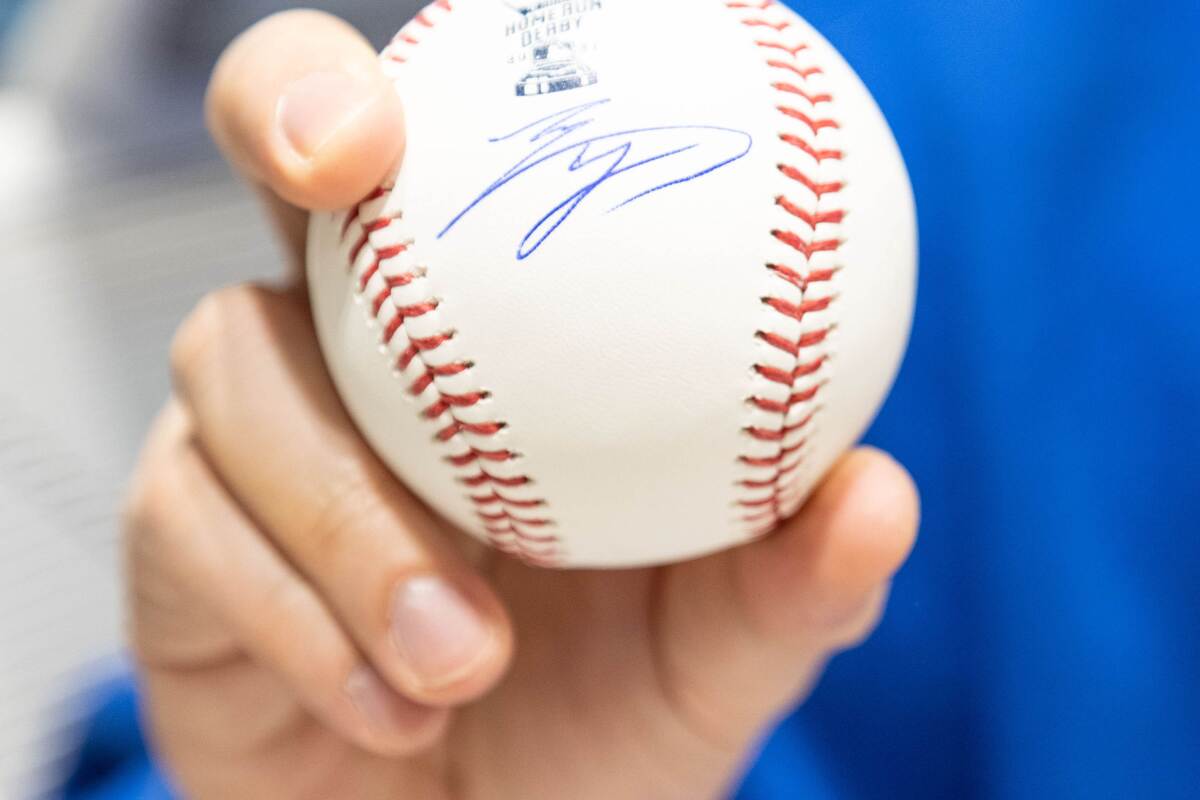

1. A ball signed by Ohtani. 2. An Ohtani bobblehead. (Jean Chung / For The Times)

Members were captivated by Ohtani’s monastic self-discipline, the lore of how he lived in a team dormitory while making $2 million a year in Japan, or how he gave his entire salary to his parents to manage, living off a monthly $1,000 allowance. He picks up trash on the field. He doesn’t hock loogies. He is intensely competitive but without any of the suffocating self-seriousness or egotism of so many superstars.

One moment in particular sticks out for Lee.

It’s Sept. 29, 2022, and Ohtani has almost pitched a no-hitter against the Oakland Athletics. But in the eighth inning, with just four outs left, Angels shortstop Liván Soto fumbles a grounder hit by Conner Capel. Soto, who was just promoted to the majors, looks crushed. But Ohtani playfully consoles him, without a trace of frustration on his face.

“Watching Ohtani live with such a strong sense of who he is reminds me of the regrets I’ve had in my life,” said Heo Jeong-koo, a 53-year-old bus driver and fan club member.

Lee Jae-ik bought a Porsche Cayenne after reading that Shohei Ohtani drove one.

(Jean Chung / For The Times)

He wished he hadn’t spent so much of his youth trying to live up to an ideal of aggressive masculinity imposed on his generation. He wished that he had been gentler with his sons.

“I treated them harshly because I bought into certain ideas about how men should behave and I know that hurt them,” Heo said. “But Ohtani isn’t like that. He was a good kid. He shows you that losing your temper doesn’t help anything, and he made his own success by being that way. I love that about him.”

Heo walks around decked out in Ohtani gear, proselytizing to anyone who will listen. He studies Ohtani’s habits from high school, applying them to his own life. His friends have told him: “Watch out, Jeong-koo, this is going to turn into a religion if you’re not careful.”

: :

The fan club now has around 500 members, but Lee expects many more after the season openers.

Apart from buying some ad space in a subway station last year, he has avoided aggressively promoting the group.

“I want people to seek it out organically,” he said. “I don’t want people looking for free stuff from the giveaways.”

Lee Jae-ik, third from right, waits to greet Ohtani at Incheon International Airport on Friday.

(Jean Chung / For The Times)

The club has had two offline meetings, the second one at a rented conference room where Lee, in his blue Dodgers hoodie and cap, paced around by the white board emceeing an Ohtani trivia game, reviewing the details for the airport welcoming party and moderating a half-hour conversation about Ohtani’s new wife.

“Do men also have this feeling? This sense of loss?” one of the female attendees asked.

“Yeah, we do,” Lee said. “I have no idea why I’m so interested in someone else’s spouse. But maybe it’s good that he got married. No distractions to his baseball.”

Even in person, the members refer to one another by their online handles. Lee’s translates to “the museum director” on account of his vast collection of Ohtani memorabilia.

Some have crossed over from K-pop fandom, including one woman who had managed to buy three tickets for the season openers, despite seats having been sold out in minutes.

“The trick is to go to a PC cafe with a good internet connection and have everything set up so you can pull the trigger immediately,” she explained.

“I have experience from doing this as a BTS fan.”

: :

There is a part of Lee that acknowledges all of this was a calculated effort angled toward one day meeting Ohtani. His greatest wish is to interview him.

At the airport, Lee held a signed copy of his book, which he inscribed: “I wrote this book for you.”

He and the other fans had been waiting for hours now, and the initial bustle had died down to a drowsy murmur. The banner, in the afternoon sunlight, almost looked radiant.

Shohei Ohtani arrives to the greetings of fans at Incheon International Airport on Friday.

(Jean Chung / For The Times)

Lee checked the flight tracker on his phone. “They’re close,” he reported.

At 2:47 p.m., Ohtani was the first of the Dodgers to appear, a head taller than the rest of his entourage. His eyes cast about the roaring scene before him before landing on the banner. Lee is adamant their gazes met, and for a second, it looked as though he were walking straight at them.

Then Ohtani smiled, waved and disappeared through the door.

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : LA Times – https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2024-03-18/how-a-south-korean-radio-producer-came-to-worship-dodger-superstar-shohei-ohtani