By Jeremy Wilkinson, Open Justice reporter of

A Disputes Tribunal ruling has found a man sold fake coins did not have an avenue for redress against the auction house. (File photo).

Photo: 123rf

A small auction house has been accused of selling fake rare coins and bullions which has drawn the ire of numismatists (coin authenticators) throughout the country. However, a tribunal has ruled it cannot stop the auction house from selling fakes and that it’s up to the buyer to do their due diligence. Jeremy Wilkinson investigates.

The coin-collecting community is a small, tight-knit and passionate one in New Zealand so when someone starts selling fakes it quickly starts to make waves.

Lipscombe Auction House in Nelson sells hundreds of rare coins per year, specimens that would go for thousands if they were genuine.

But some of them are not real, as one buyer who spent nearly $8000 on various coins and supposedly silver bullions found out.

A Disputes Tribunal decision released early this year describes how one man paid $6000 for some coins and sent them away to get tested for silver content.

While he was waiting on the results he spent a further $1500 on coins and bullions from Lipscombe only for the results of the first batch to come back with a disappointing result.

They were all fakes.

The buyer refused to complete the pending sale of $1500. He contended the first lot he’d purchased and tested was essentially worthless so he believed it was likely the second lot was the same.

Lipscombe then took him to the tribunal and won, meaning the man has to complete the sale. The adjudicator also dismissed the buyer’s counterclaim for a refund of the first $6000.

It’s a move that’s got other auctioneers of rare goods and buyers of rare coins talking, but experts say the auction house is not doing anything illegal.

However, some of them believe it’s unethical and not the way they’d expect an auctioneer to behave.

The buyer purchased a number of ingots similar to the ones pictured.

Photo: Supplied/ Open Justice

Senior numismatist and expert coin authenticator Liam Jennings told NZME he believed it was an auctioneer’s ethical duty to verify that what they sell is genuine.

In his opinion, auctioneers who do not do that “ruin the trust in the collector market and make it harder for genuine people to do good trades”.

Jennings is employed full-time authenticating coins – known in the business as a numismatist – and bullions at Mowbrays Auction House on the Kāpiti Coast, the largest auction house for rare coins in the country.

Its policy is to authenticate everything that comes through its doors and it refuses to sell anything found to be a fake.

If on the off-chance an item slips through the cracks and a fake is sold as the genuine article, they refund it.

Jennings said people who sold fakes were “ripping people off for their good money”.

One of the country’s leading legal experts in consumer and intellectual property law, Ian Finch, said Lipscombe was not doing anything illegal.

“I can see where the adjudicator landed where they did, but at the same time on a different day with a different adjudicator it could just as easily have gone the other way,” he said.

Buyers needed to take the same precautions they should be taking when purchasing a car and do their due diligence about authenticating the product themselves, Finch said.

Having looked at Lipscombe’s terms and conditions as well as its auction descriptions, Finch said he believed the auction house was not “taking personal responsibility for the product”.

He said its wording was quite “glib”, which provided a legal out for the auctioneer in not making any promises about the authenticity of the product.

“They are basically face-value descriptions,” Finch said.

He said that if a buyer was willing to spend $8000 on coins they needed to be careful, and if an auction house started authenticating some things it would have to do that for everything it sold.

“Personally I’m not entirely sure where I sit on it, though I definitely have sympathy for the purchaser.”

Lipscombe Auction House changed ownership within the past 10 years and its new owner and auctioneer, Warwick Savage, told NZME the Disputes Tribunal decisions were private. However, the decision was published on the Ministry of Justice website, albeit with the names of those involved redacted.

NZME cross-referenced the auction dates and purchased goods with those listed in the decision.

“We have already had legal opinions, everything, even the Disputes Tribunal have gone on our side,” Savage said when contacted by NZME.

“We are trading completely legally and we’ve had confirmation of that through our lawyer, through everybody involved. We make it clear that we do not authenticate, so it’s buyer beware.

“We won at the Disputes Tribunal and as far as I’m concerned that’s the end of it.”

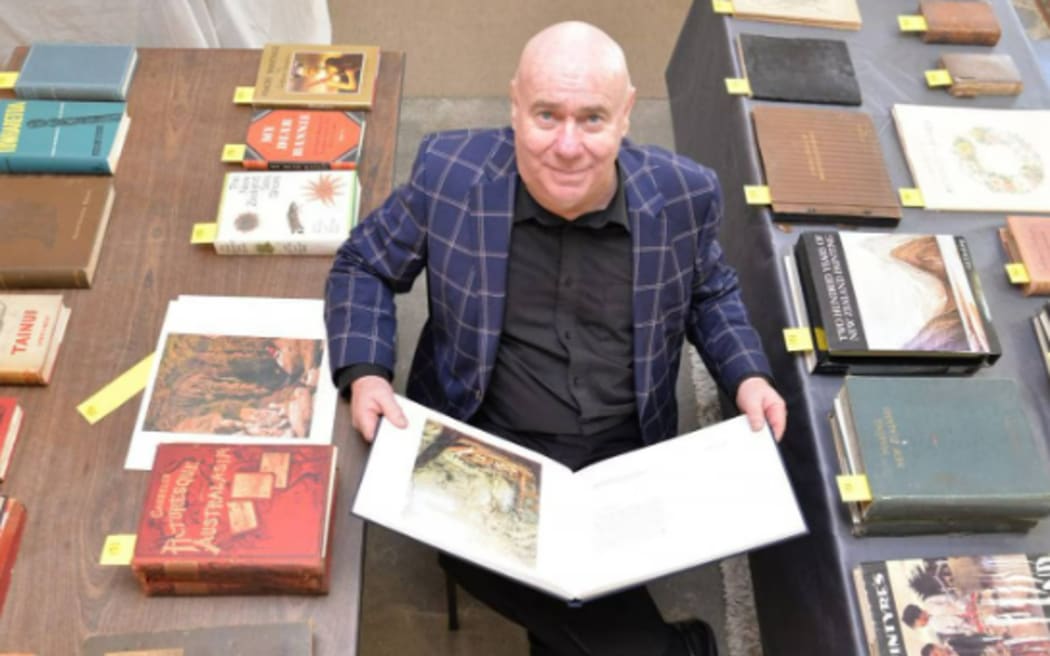

Lipscombe owner and auctioneer Warwick Savage said his auction house did absolutely nothing wrong.

Photo: Supplied/ Open Justice/ Nelson Weekly – Andrew Board

Savage did not respond to further questions posed by NZME.

Caveat emptor

The Latin phrase “caveat emptor” loosely translates to “buyer beware” and essentially places the burden on the buyer in any sale to reasonably examine property before they purchase it.

At times, the phrase “as is where is” is used at auctions, which is basically an informal statement of terms and conditions that if anything breaks or goes wrong it is up to whoever purchased it to check it over properly.

Lipscombe Auction House had its terms and conditions listed on its website which stated it was not liable for any error whatsoever to do with the “condition, state, size, quality or quantity” of anything it listed.

Its descriptions did not state any coin was genuine and were merely descriptions of the coins or what was written on them, such as: “USA Silver Coins x 4″ and “Australian 1937 Crown” and “1925 USA Half Dollar”, to name a few.

It was these descriptions that Disputes Tribunal adjudicator Dolly Brennan zeroed in on when she made her ruling that the buyer was obligated to complete the second purchase despite already having spent thousands on fakes.

Brennan ruled that many of the coins and ingots were not described specifically as having a silver content, though the word silver was used in the auction listing.

“Using the word ‘silver’ in this context is descriptive of the face of the item being described, rather than a representation that it is made of silver or regarding its quality or authenticity,” she said.

The buyer argued that using the word silver conveyed to a reasonable person that it would contain the precious metal rather than it simply being a description of how the item looked. Brennan disagreed.

The buyer also argued the descriptions of the coins denoted a specific year which was indicative of their being minted in a particular era. Brennan ruled that Lipscombe was merely describing what was written on the coin.

As well as the coins, the buyer purchased a series of silver ingots which were described as “.999 fine silver”. These turned out to be only silver-plated.

Ultimately Brennan ruled in favour of Lipscombe and ordered that the buyer complete the sale of $1500 worth of coins and bullions, despite the first lot of $6000 having been proved to be fake.

A lawyer acting on behalf of Lipscombe told the Disputes Tribunal all its auctions were “buyer beware” and the goods were sold “as is where is” and the risk of quality and authenticity lay solely with the purchaser.

The lawyer said Lipscombe had to run its auctions in such a way because its auctioneers did not have the skills nor resources to authenticate the items they sold.

The lawyer, who was not named in the decision, said Lipscombe did not dispute that the first lot of items sold to the buyer were fakes but they were sold in accordance with its terms and conditions. They argued that Lipscombe was not responsible for any losses the buyer incurred by purchasing a bulk lot of fake coins.

Brennan ruled that any potential bidders on any of Lipscombe’s online auctions must tick a box that confirmed they had read and understand the terms and conditions and were in turn bound by those terms.

She also ruled that according to Lipscombe’s terms and conditions, it would only grant a refund for a fake if they had specifically made a claim about the genuineness of the product.

Brennan acknowledged the buyer would be disappointed with her ruling and was “very upset” that Lipscombe appeared to be continuing to sell coins and ingots similar to the fakes he had purchased.

“However, the tribunal has no jurisdiction to prevent [Lipscombe] continuing to sell such items,” she said.

Normally when a buyer felt they had been wronged by an auctioneer they could approach the Auctioneers Association with a complaint.

However, Lipscombe was not a member and as such had no obligation to adhere to the association’s code of ethics.

Lipscombe Auction House, in Nelson.

Photo: Supplied/ Open Justice/ Tracy Neal

Association chairman John Mowbray said he had received as many as 10 complaints in recent years about Lipscombe, but there was not much he could do because the auction house was not a member.

“People have been contacting us because they simply don’t know what to do,” he said.

In Mowbray’s opinion, if a customer complained about the authenticity of a product they had purchased then the auctioneer was honour-bound to cancel the auction.

Mowbray believed what Lipscombe was doing was wrong ethically, but not illegal.

In his opinion, it was however a “complete variance” to how he would expect an auctioneer to behave.

It was also at odds with the way he said he runs his own business.

“While the onus isn’t technically on an auction house or seller to authenticate a product … it’s the right thing to do,” he said.

For his part, Mowbray said he had complained to the Registrar of Auctioneers about Lipscombe.

That registrar, Duncan Connor, is employed by the Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment and told NZME in an emailed statement that there were currently no active complaints against Lipscombe Auction House.

“The Registrar was made aware of one historic concern regarding Lipscombe Auction House that indicated a potential breach of the Auctioneers Act 2013. The matter was resolved before any further inquiries were conducted,” he said.

“Our advice to consumers when buying and selling at auctions is to exercise due diligence before placing a bid at an auction and read the terms of contract/sale carefully.”

Connor recommended anyone who thought an auctioneer had misled them should go to the Disputes Tribunal or the Commerce Commission. He said complaints involving forgery should be referred to the police.

For its part, the Commerce Commission said it had not investigated Lipscombe and could not specifically comment.

However, advice from the commission on its website in an advisory warning against an influx of counterfeit clothing for sale said that “selling counterfeit goods harms both the consumer and legitimate businesses”.

“Consumers should remember the golden rule – if it seems too good to be true, it probably is,” that advice said.

Too Good to be True

NZME was unable to locate the buyer in the Disputes Tribunal decision as their name was redacted, however there were multiple warnings in online reviews about the auction house and its practices.

British-based Ben Spavins purchased over $250 worth of coins from Lipscombe only to find out they were fake almost as soon as he got them out of the packet.

Spavins said he tried calling the auction house multiple times but was “fobbed-off”, and when he finally got through to the manager he would not apologise nor admit any wrongdoing.

“They were quite arrogant by email and kind of bragged about having won in the Disputes Tribunal before,” he said.

“When you see the auction description and it says ‘silver’ you think it’s going to be actual silver and when it says ‘USA’ you’d expect it to be legal currency.”

Spavins said “it’s a massive stretch to say that silver is just describing how it looks. I mean the New Zealand 50-cent piece looks silver, but everyone, including the general public, knows it’s not actually made of silver.”

Spavins said he had dealt with Lipscombe before the ownership change and they’d had a good reputation, which was why he did not think twice before bidding on the auctions.

“I suppose that’s why it’s especially disappointing, because they used to have such a good reputation.”

Lipscombe did actually refund Spavins but said in its email that it was not obligated to and was doing so out of good faith.

In numerous responses on social media to customers who had purchased fakes or commented warning others that Lipscombe did not authenticate its goods, the auction house repeatedly pointed out its terms and conditions: “We clearly state in our terms and conditions and all related material that we cannot guarantee or authenticate any items in the Auction, it is buyer beware. We do not have the expertise to make such calls and have received no specifics from the vendor on this coin,” was the auction house’s general response to these accusations.

The Royal Numismatic Society of New Zealand had hundreds of members who meet to discuss and trade rare coins.

The society’s president David Gault said it was a shame Lipscombe was selling coins it apparently knew to be fake.

“If you have a reputable dealer or auction house most people would expect them to stand behind what they’re selling,” he said.

“This is what most dealers in New Zealand would do at least, and most of them wouldn’t sell a replica unless it was clearly identified as such.”

Gault said there was an ethical onus on the auction house to satisfy itself that what it was selling was genuine and doing so was simply ethical trading.

“In my own view, there’s a moral obligation for the auctioneer to go further than simply buyer beware.”

– This story originally appeared in the NZ Herald.

Photo: Open Justice

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : RNZ – https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/500846/buyer-beware-lipscombe-auction-house-selling-fake-rare-coins-can-not-be-stopped