Elon Musk’s Tesla Roadster and Starman manikin shortly after launch on February 6, 2018. Photo: SpaceX

Being the space nerd that I am, I often imagine a museum filled with the most important objects ever sent to space. We couldn’t possibly build a place like this, but we can speculate as to which human artifacts deserve a place in our imaginary spaceflight museum.

Most things sent to space are utilitarian in nature and are now of little practical value, unless they’re still functioning. Our artifacts can be found orbiting the Earth and Sun, sitting on the surfaces of planets and moons, and even flying through interstellar space.

Some of these relics are more valuable than others, and by “valuable” I mean from a historic, nostalgic, or scientific perspective. To come up with this list, I reviewed my favorite moments in space history—and consulted with astronomer Jonathan McDowell for anything I may have missed.

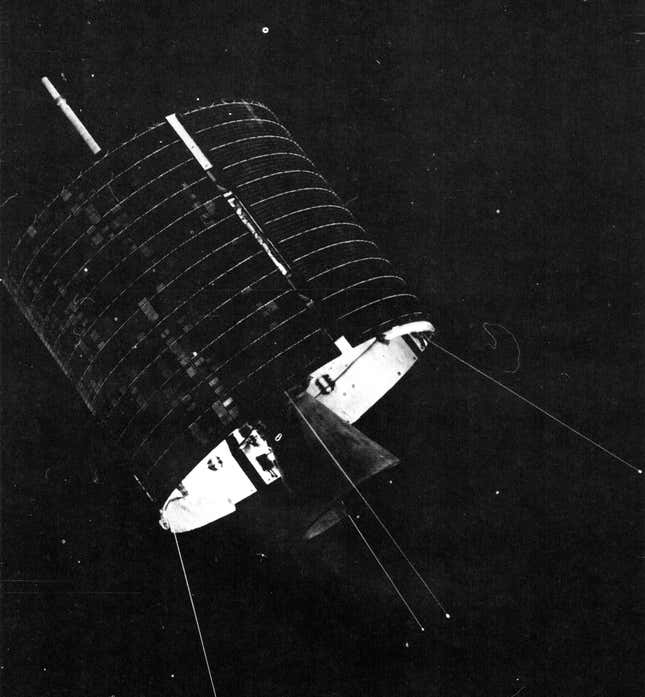

Photo of Vanguard 1.Photo: NASA

This spiky little guy would be a welcome addition to our museum. Launched on March 17, 1958, Vanguard 1 is the oldest satellite currently in Earth orbit, according to NASA. The batteries in the 3.21-pound, spherical spacecraft died several months after launch, but the satellite is expected to remain in orbit for another 175 years, as it was launched into an elongated 406 by 2,466 mile (654 by 3,969 km) orbit. The U.S. Department of Defense used Vanguard 1 to test a three-stage rocket and to analyze the effects of space on satellites (this was just the second satellite launched by the United States). It was also the first satellite to use solar cell power. It warms my heart to know that this old-timey satellite is still up there spinning around Earth.

Technicians working on the TIROS-1 satellite.Photo: NASA

The Television and InfraRed Observation Satellite, or TIROS-1, was the first weather satellite launched to space and NASA’s “first experimental step to determine if satellites could be useful in the study of the Earth,” according to the space agency. As such, it carries tremendous historical value, given our current dependence on weather satellites. The mission was a big success, providing the first space-based meteorological data used for weather forecasts (despite the satellite operating for just 78 days). TIROS-1 launched on April 1, 1960 into a high-altitude low Earth orbit, where it still resides today.

Artistic impression of the Luna 2 spacecraft. Image: NASA

Luna 1, built and operated by the USSR, is the first spacecraft to reach the Moon. Fitted with five antennas but no propulsion system, Luna 1 launched on January 2, 1959. They were hoping to intentionally crash the spacecraft onto the Moon, but it instead passed to within 3,725 miles (5,995 km) of the lunar surface and entered into an orbit around the Sun, also known as a heliocentric orbit, somewhere between the orbits of Earth and Mars. The subsequent mission, Luna 2, successfully crashed onto the Moon, becoming the first human-made object to reach the surface of another celestial body.

Scientist James Van Allen inspecting the cone-shaped Pioneer 4 probe prior to launch. Photo: NASA/JPL

Launched on March 3, 1959, NASA’s 13-pound Pioneer 4 probe passed by the Moon at a distance of 37,000 miles (60,000 km). It failed to photograph the Moon as planned, but Pioneer 4 became the first U.S.-built spacecraft to escape Earth’s gravity and enter into a heliocentric orbit, where it remains to this day. A fine addition to our spaceflight museum.

Photo: NASA/Bell Labs

Launched by NASA on July 10, 1962, Telstar was the first privately funded space-faring mission and the first commercially owned satellite to reach space. NASA explains its significance:

Although operational for only a few months and relaying television signals of a brief duration, Telstar immediately captured the imagination of the world. The first images, those of President John F. Kennedy and of singer Yves Montand from France, along with clips of sporting events, images of the American flag waving in the breeze and a still image of Mount Rushmore, were precursors of the global communications that today are mostly taken for granted.

And let’s not forget the song “Telstar” by one of my all-time favorite groups, The Ventures. Telstar is currently spinning around our planet in a medium Earth orbit. Its gigantic cultural influence, more than its technological contribution, earns it a place in our museum.

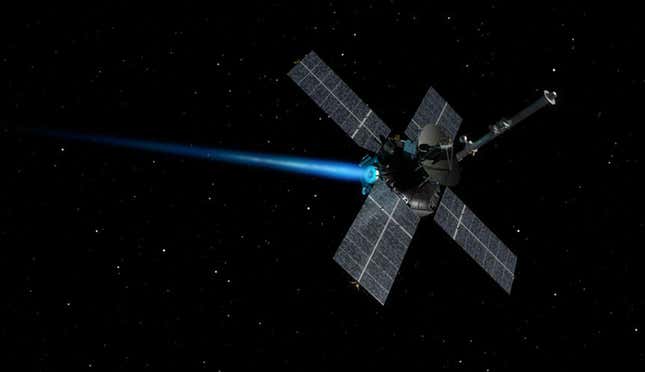

Rendering of Intelsat 1. Illustration: NASA

Intelsat 1 was the first commercial communications satellite sent to geosynchronous orbit, reaching this destination on April 6, 1965. Nicknamed “Early Bird,” it was built by the Hughes Spacecraft Company (now Boeing Satellite Systems) for the Communications Satellite Corporation (COMSAT) global telecommunications company. It’s historically significant in that it was the “first to provide direct and nearly instantaneous communications contact between Europe and North America,” as NASA explains. The 76-pound Early Bird worked for 18 months but was brought back online during the Apollo 11 mission. It’s no longer working, but it’s still up there, some 22,300 miles (35,890 km) above the equator.

Impression of Mariner 4 performing an engine burn. Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech

NASA’s Mariner 4 spacecraft is currently idle and in orbit around the Sun, but its historical legacy is secure. Mariner 4 flew past Mars on July 15, 1965, becoming the first spacecraft to take close-up photos of another planet. The probe was expected to survive for only eight months after its Mars encounter, but it managed to work for another three years while in solar orbit, “continuing long-term studies of the solar wind environment and making coordinated measurements with Mariner 5, a sister ship launched to Venus in 1967,” as NASA explains.

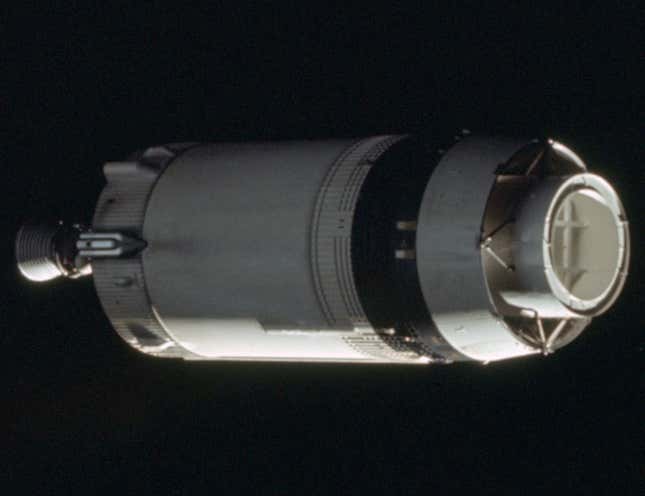

The Apollo 8 S-IVB shortly after separation. Photo: NASA

Five third stage boosters belonging to Saturn V rockets used during the Apollo missions are also lost in space. Formally known as the S-IVB (pronounced “S-four-B”), the third stage boosters sent the crewed command modules on their missions through cislunar space. The S-IVBs used in Apollo missions 8 through 12 are currently adrift in space, but those that followed (Apollo 13 to 17) were deliberately crashed onto the Moon for scientific purposes.

In 2002, astronomers spotted what they believe to be the S-IVB belonging to the Apollo 12 mission, giving it the designation J002E3. According to CNEOS, the object is easily detectable in asteroid surveys and is bright enough to be seen by amateur astronomers. J002E3, like the other S-IVBs, was in a heliocentric orbit, but it was captured by Earth’s gravity in April of 2002—so technically it’s now an artificial moon of Earth.

Replica of the gold olive branch deposited on the lunar surface during Apollo 11. Photo: NASA

During the Apollo 11 mission in July 1969, NASA astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin deposited a small gold olive branch—a symbol of peace—onto the lunar surface. This relic is of tremendous historic importance, and its meaning and promise is something that should be kept in mind as we head deeper into the new space race.

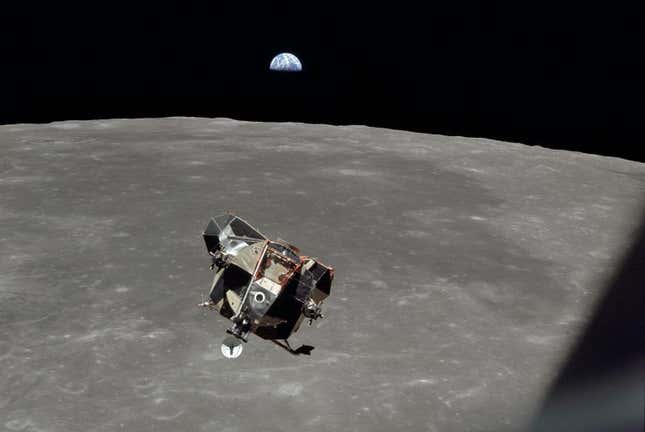

The Eagle ascent stage prior to rendezvous with the command module Columbia.Photo: NASA

The fate of the Apollo 11 Eagle ascent stage is unknown, but research from 2021 suggests it stayed in space and settled into a lunar orbit, where it remains to the present day. As a key component of the Eagle spacecraft and the first crewed landing on the Moon, the ascent stage has obvious sentimental value.

The Venera 7 probe.Photo: NASA

Venera 7 has been lying on the Venusian surface for over 50 years, so there might not be much left of the Soviet probe—the first to reach the surface of Earth’s evil twin. We know that Venera 7, with the help of parachutes, safely reached the ground in December 1970 because it managed to transmit signals for roughly 23 minutes before finally expiring. The probe’s sensors showed temperatures in excess of 475 degrees Celsius, so we can only imagine what Venera 7 looks like today.

One of two golf balls left on the lunar surface can be seen just below the discarded javelin. Photo: NASA

NASA maintains a jaw-dropping catalog of all human-made material left on the Moon, and it’s dauntingly huge (that said, it hasn’t been updated since 2012, so some items are missing, namely the remnants of the crashed Beresheet probe and Chandrayaan-2 Moon lander). NASA’s list contains a surprising assortment of items, including lens caps, hammers, tripods, nail clippers, and earplugs.

Among the more entertaining items are two golf balls and a javelin (a modified scoop handle), which NASA astronaut Alan Shepard brought to the Moon in 1971 during the Apollo 14 mission. As Shepard famously said after striking the second ball, it traveled “miles and miles and miles” owing to the low gravity. The balls and javelin are the most famous sporting goods in space, earning a place in our museum.

A waste bag and packaging materials left behind from the Apollo 11 mission. Photo: NASA

It’s my strong opinion that all Apollo landing sites should be left alone and treated as protected areas. That said, there are some items of scientific value that should be retrieved, including the human waste bags left behind by the astronauts. These bags, containing urine and poop, contain biological materials that scientists would very much like to study. Any microbes, such as bacteria, that once lived in these waste products are probably long dead, but biologists would like to prove that for certain, as it speaks to the potential for interplanetary microbial contamination.

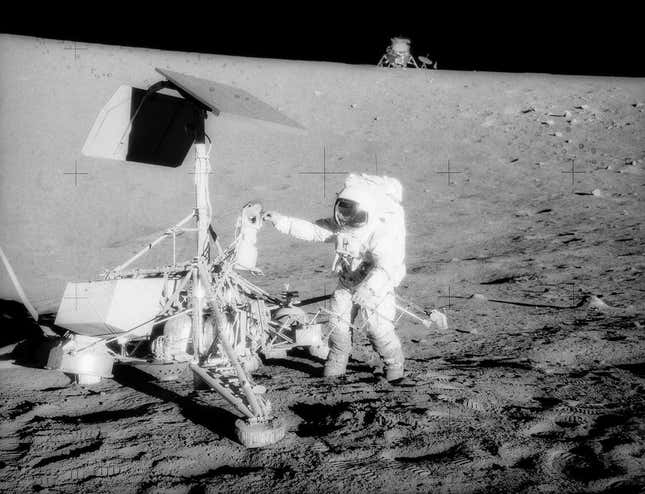

An Apollo 12 astronaut visiting Surveyor 3.Photo: NASA

NASA’s Surveyor 3 lander is the first and only human-built probe to be visited by humans on the surface of another celestial body. From 1966 to 1968, the space agency sent Surveyor 3, along with a batch of similar landers, to the Moon in advance of the Apollo missions. Five of the seven Surveyors sent to the Moon performed successful soft landings, but only Surveyor 3 was re-visited, a feat accomplished during Apollo 12. I’d very much like to see us reunited with the lander for a second time.

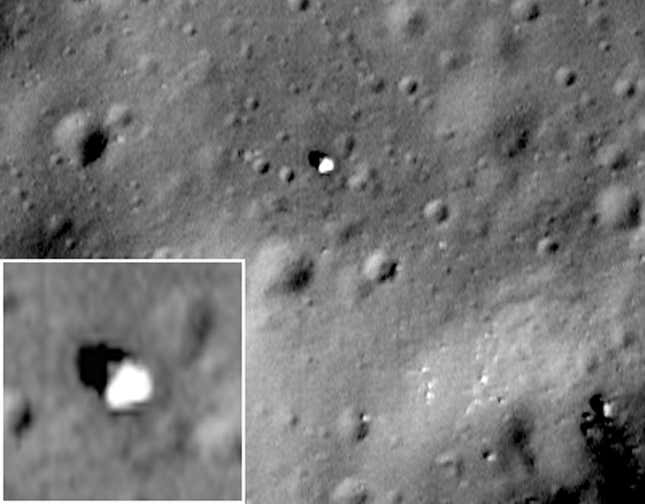

Image: NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

The first wheeled rover to reach the lunar surface did so on November 17, 1970. The eight-wheeled Soviet rover, named Lunokhod 1, sent back valuable information about the composition of the lunar regolith (soil) and the local topography, before finally expiring. The rover is currently collecting dust in Mare Imbrium, but its lander is clearly visible to lunar satellites passing overhead. We know where you are, Lunokhod 1.

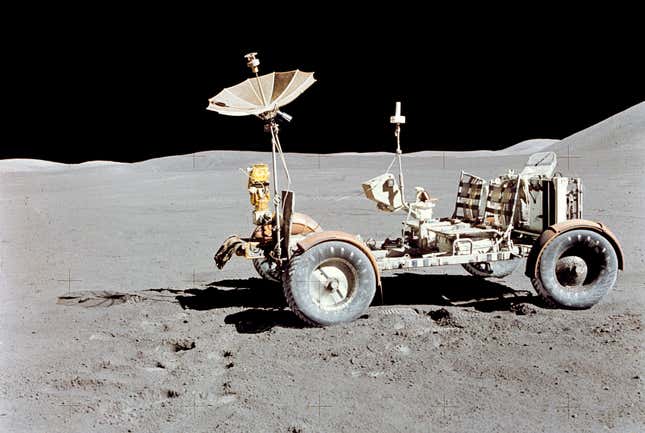

The Lunar Roving Vehicle from the Apollo 15 mission Photo: NASA

The Apollo astronauts left three Lunar Roving Vehicles, or LRVs, behind. These are the first cars to be driven on another celestial body—an accomplishment that still boggles my mind. These Moon buggies, as they were affectionately called, were amazingly reliable, transporting astronauts and cargo across dozens of miles during the course of the Apollo 15, 16, and 17 missions. Maybe we can make an exception to my “leave the Apollo artifacts alone” rule and retrieve one of these buggies for the spaceflight museum.

Artist’s conception of Pioneer 10 heading into interstellar space. Illustration: NASA/Ames

Launched on March 2, 1972, Pioneer 10 was NASA’s first mission to visit an outer planet, flying past Jupiter on December 4, 1973. The probe then crossed Saturn’s and Neptune’s orbit, as it ventured farther than any spacecraft before it. Pioneer 10’s final signal was received in January 2003, and it’s now heading out of the solar system in the direction of the red star Aldebaran. The probe would make for a fine museum installation, but it’s now way out of reach and likely lost to space forever. But that’s all good, as it contains an informative plaque should it eventually be intercepted by aliens.

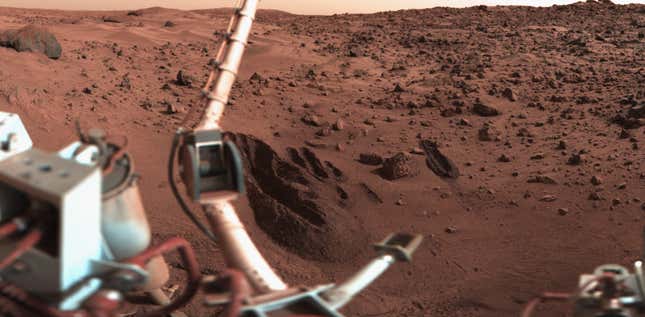

Trenches dug by the Viking 1 lander on Mars. Photo: NASA

NASA’s Viking 1 lander reached the surface of Mars on July 20, 1976, where it took exhilarating photos of the dusty and rock-strewn surface. The stationary probe worked for four years on the western slope of Chryse Planitia, gathering important chemical data about the Martian regolith. Viking 1, as the first lander to reach the Red Planet, certainly belongs in our imaginary museum, but the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum has already claimed ownership of the artifact. Yes, really. Humph.

Artist’s impression of the Spitzer Space Telescope. Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Two retired space-based telescopes, Spitzer and Kepler, would be a great fit for our museum. NASA’s infrared Spitzer worked from 2003 to 2020, collecting astronomical data about stellar nurseries, hot Jupiters, and distant stars, among other celestial phenomena. NASA’s Kepler, in operation from 2009 to 2018, was an intrepid planet hunter, helping astronomers to identify more than 2,600 exoplanets. Spitzer and Kepler remain in space, with the former trailing Earth along its orbit and the latter in orbit around the Sun.

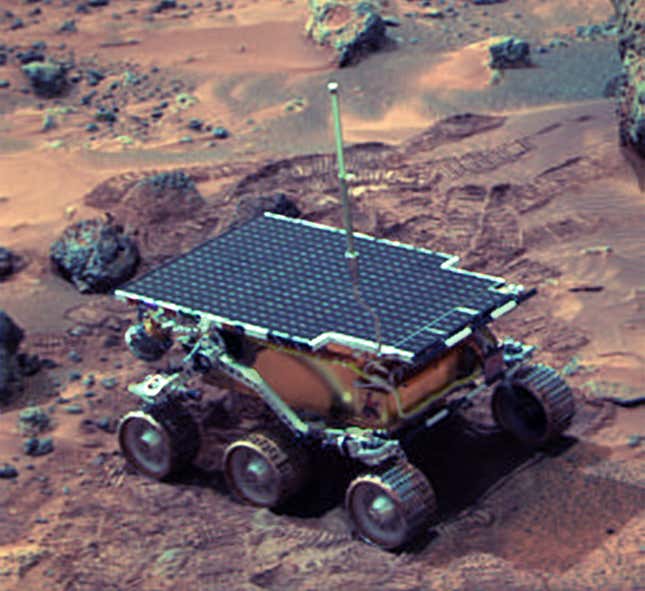

The Sojourner rover working on Mars. Image: NASA

NASA’s 25-pound Sojourner rover, in addition to being the most adorable robot ever sent to space, is the first wheeled vehicle to rove around the surface of another planet. As a key component of the 1997 Mars Pathfinder Mission, Sojourner spent 83 days exploring the Red Planet, taking photos and gathering chemical and atmospheric data. It’s still out there on the plains of Chryse Planitia, though likely covered in a thick layer of red Martian dust.

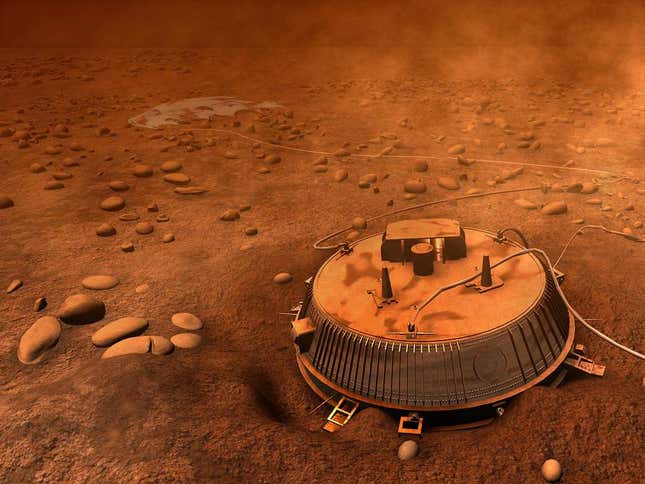

Artist’s impression of Huygens probe on Titan. Image: ESA

The European Space Agency’s pioneering Huygens probe is lying somewhere on the surface of Saturn’s moon Titan. Well, unless it got gobbled into Titan’s thick, oily seas. The probe landed on the murky moon on January 14, 2005 following a 27-minute parachute-assisted descent to the surface. The probe lived for just 72 minutes, but it’s the first and only landing to be successfully performed in the outer solar system, thereby earning a place in our museum.

The red Tesla Roadster and Starman manikin shortly after launch. Photo: SpaceX

It still blows my mind to know that a car—specifically Elon Musk’s Tesla Roadster—is currently in a heliocentric orbit beyond the orbit of Mars. The SpaceX CEO made it the dummy payload during the inaugural launch of the company’s Falcon Heavy rocket on February 2, 2018. A manikin named “Starman” went along for the ride, which, together with the Tesla Roadster, should also be considered for our improbable museum.

This article originally appeared in Gizmodo.

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : Quartz – https://qz.com/the-most-interesting-human-made-objects-ever-left-in-sp-1851112550