The history of extractivism in the Pan Amazon shows that environmental damage has been commonplace, only now there are new demands from the parent companies that influence all service providers involved.In this section, Killeen explains that any hydrocarbon project (whether oil or gas) entails a high risk of social conflict with the communities living next to exploration and exploitation areas.The governments of countries such as Ecuador, Peru, Colombia and Brazil must ensure that there is real environmental responsibility for the oil spills that are damaging ecosystems and the livelihoods of communities.

The petroleum industry has a long history of operational calamities, large and small, that has created an equally long history of efforts to manage the environmental and social liabilities that are an inherent outcome of their business model. This includes both corporate and governmental actions that seek to mitigate the impact of their day-to-day operations as well as to remediate damage caused by negligence, ageing infrastructure or acts of God.

The environmental policies of oil companies were grossly inadequate until about fifty years ago, when the nascent environmental movement demanded action following several high-profile disasters that wrought havoc on natural ecosystems and human communities. Both the scale of these environmental disasters and the inherent toxicity of crude oil forced a fundamental reform on the industry. Reform was first imposed upon the oil giants, and soon extended down through their supply chains to change the practices of their international service providers and state-owned partners in developing countries.

In 1990, the petroleum industry in the Pan Amazon was dominated by state-owned companies which had inherited the oil fields and pipeline systems from multinational companies that had pioneered the industry in the 1960s and 1970s. Unfortunately, most had maintained the pre-reform practices of their private sector progenitors. Change came in the unlikely form of the Washington Consensus, a controversial suite of policies imposed by multilateral agencies to foster economic growth via the private sector, which included the promotion of direct foreign investment in the hydrocarbon sector. The return of foreign (Western) oil companies in the 1990s changed how oil fields and pipelines were managed, because they also introduced the emerging concepts of sustainability into the hydrocarbon sector.

The criteria of sustainability concepts have evolved over time and now span six major themes that reflect the current emphasis on ESG investment. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, when the oil and gas boom was underway in the Pan Amazon, companies emphasized mitigating the impacts of operations on biodiversity and aquatic systems via avoidance and remediation (cleanup). Social programmes focused on engagement with local communities with the objective of avoiding opposition to their activities. To this end, these programmes sought to generate ‘goodwill’ by building schools, clinics and basic infrastructure. Companies were motivated by the imperatives of risk management. Projects in the Amazon always incorporate a relatively high element of risk because of the region’s notoriety and importance as a biodiversity and cultural hotspot. Social conflict, particularly involving an Indigenous group, can paralyze a project and render a multi-decade investment inviable.

Western oil companies obligated local service providers to embrace the sustainability philosophies as a prerequisite for winning a contract. Second-tier oil companies demanded the same level of compliance with environmental and social protocols, as, theoretically, did the state-owned companies from Russia and China.

Petrobras anticipated these reforms because its executives have long aspired to build a global company able to compete with the super-majors. By 2000, the state-owned companies in the Andean republics had likewise implemented environmental and social criteria into their business practices; nonetheless, they are frequently involved in controversies because their executives are obligated to execute policies dictated by elected officials that run counter to the principles of sustainability.

In addition to state-owned corporations that operate oil fields and pipelines, governments also have ministries that promote the development of the extractive sector, as well as regulatory entities that impose rules reflecting the principles of sustainability and good governance. Most of these agencies were established (or reformed) in the late 1990s by the same multilateral agencies charged with implementing and financing the Washington Consensus. The objective was to separate the policy-making ministries that implement initiatives sponsored by elected governments from the regulatory process that should, theoretically, protect society from malfeasance and negligence, while providing legal security for investors.

Drill baby drill – exploration and production

The hydrocarbon industry is based on the permanent need to discover and develop new sources of oil and gas. Exploration begins with a seismic survey, which in the Amazon will employ hundreds of unskilled workers who cut thousands of kilometers of transects and clear hundreds of hectares of forest to create campsites and helipads across tens of thousands of square kilometers of wilderness. Fortunately, the impacts are short-lived because the natural forest ecosystem remains intact and, within a couple of years, little evidence remains of the seismic crew’s presence. The risk is greater for Indigenous communities, particularly those living in voluntary isolation. In most cases, they will avoid contact, but even a brief encounter would be catastrophic for individuals that lack immunity to many common diseases (see Chapter 11). More ominously, the potential discovery of oil or gas is a powerful disincentive for establishing an indigenous reserve, which is essential for providing these groups with long-term security.

The number and extent of seismic surveys reached its peak between 1990 and 2010 and has decreased over the past decade. Nonetheless, geophysical studies continue to be programmed by the governments of Ecuador and Brazil, a clear signal that they intend to expand operations over the medium term, because seismic data is used to locate exploration wells. Typically, this involves drilling between five and ten wells within a concession that spans between 100,000 and 300,000 hectares. Unless they are located very close to an existing road system, river transport is used for heavy machinery, and helicopters and mid-sized aircraft for personnel. Roads may be built to connect drilling pads, but these are rarely connected to regional transportation systems, at least not until there is a discovery.

Each drilling pad requires a forest clearing of between two to ten hectares. Most are surrounded by a berm, which is constructed to contain crude oil that might be released accidentally during drilling operations. Each well must have a pond to contain ‘drilling muds’, highly toxic industrial chemicals, which are recycled during the operations but which must be disposed of when the well is decommissioned. Inadequate storage or disposal can contaminate both superficial and groundwater.

Unsuccessful wells (dry holes) are decommissioned and abandoned. If properly remediated, the drilling pad and mud pond will be reclaimed by the forest, but only if the compacted soil is scarified to promote natural regeneration. A successful exploration well will be converted into a production well, but will probably be capped until the development of a transportation system. In remote landscapes, this usually consists of some combination of road, barge or pipeline. Producers prefer pipelines because they are less expensive to operate and cause fewer oil spills. Gas wells can only become operational when they are connected to a pipeline.

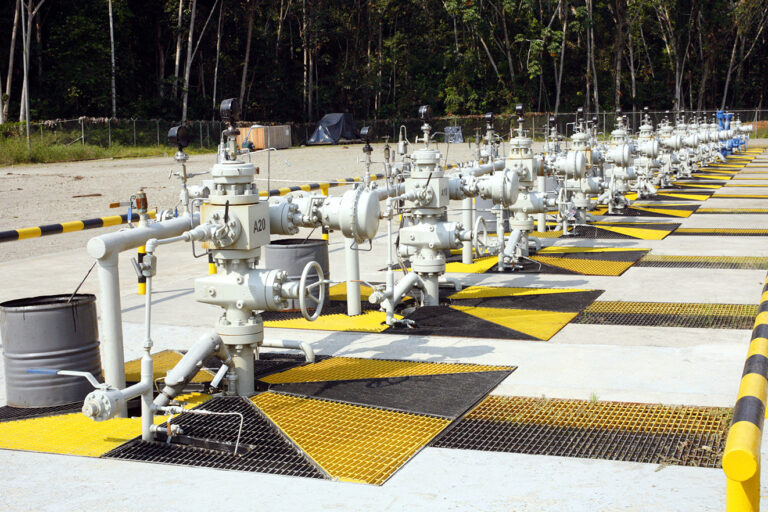

Operators will drill multiple production wells once the presence of commercial volumes of oil or gas has been verified. Prior to the 1990s, this consisted of multiple individual platforms with one or two wells established in close juxtaposition. After 2000, however, the adoption of directional drilling has allowed companies to place dozens of wells on a single platform. The ability to concentrate dozens of wells on a limited number of platforms is key to the Ecuadorian government’s strategy to exploit the reserves underneath Yasuní National Park where more than 300 wells are distributed across about 20 platforms.

Modern drilling platforms are a vast improvement over the wells established prior to the introduction of modern drilling technology and the adoption of comprehensive environmental and social criteria. The original companies (Texaco in Colombia and Ecuador and Occidental Petroleum in Peru) only made limited efforts to contain or remediate their operations. Drilling muds were dumped into unlined ponds and crude oil was used in inappropriate ways, practices that contaminated waterways and seriously impacted the health and wellbeing of Indigenous communities. These environmental liabilities have yet to be fully remediated, and Indigenous communities have been denied compensation due to the legal maneuvers of operating companies and the failure of state-owned oil companies to assume their share of the legal responsibility.

Natural gas wells are similar to, and different from, oil wells. The drilling technology is essentially the same, but oil must be pumped out of the ground while gas is simply harvested under pressure. This is particularly true in the Andean foothills where gas is trapped within super-pressurized formations. In Camisea, for example, only five platforms with 32 wells exploit the highly productive ‘megacampo’. More wells are needed to generate commercial flows from a conventional gas field, such as Urucú, which has a typical constellation of more than eighty platforms with 130 wells.

Most oil wells also produce gas, which is burnt (flared) if there are insufficient volumes to justify a gas pipeline. In Ecuador, there are reports of at least 447 separate flares and, presumably, smaller numbers in Colombia and Peru. This waste of energy is a major source of the industry’s internal greenhouse-gas emissions. Flaring is better than releasing methane into the atmosphere, but the gas can also be reinjected into wells or used locally to produce electricity. Most gas wells also produce gas-liquids, which share many of the toxic attributes of heavier forms of petroleum. At Urucú and Camisea, the separation plant that removes the gas-liquids is located in the field with parallel gas and liquid pipelines.

The average lifetime of an oil or gas well is approximately 30 years. Since the oldest fields in Colombia, Ecuador and Peru have been operating for more than 50 years, there are dozens of non-productive wells. Most are simply turned off without being fully retired, which creates a different type of environmental liability since many will leak small amounts of oil over years, if not decades, unless they are properly capped and decommissioned.

“A Perfect Storm in the Amazon” is a book by Timothy Killeen and contains the author’s viewpoints and analysis. The second edition was published by The White Horse in 2021, under the terms of a Creative Commons license (CC BY 4.0 license).

To read earlier chapters of the book, find Chapter One here, Chapter Two here, Chapter Three here and Chapter Four here.

Article published by Mayra

Amazon Mining, Environment, Gold Mining, Illegal Mining, Indigenous Communities, Indigenous Groups, Mining, Pollution

Brazil, Ecuador, Latin America, Peru, South America

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : MongaBay – https://news.mongabay.com/2024/04/the-environmental-mismanagement-of-enduring-oil-industry-impacts-in-the-pan-amazon/