Bugesera, Rwanda — When the Rwandan genocide began in 1994, Laurence Niyonagire fled her village eight months pregnant, carrying her two-year-old toddler on her back. Over the next hundred days, the Hutu ethnic majority killed 800,000 Tutsis, including Niyonagire’s parents and six siblings, as the international community stood by. After the massacres stopped, Niyonagire finally returned to her village two months later but couldn’t sleep, her mind trapped in a vicious cycle, replaying past horrors. “I walked into the road hoping a car would hit me, so I could die and pass away like the others,” she says.

Every Rwandan over age 30 has a genocide story, haunted by extreme physical and psychological violence. But in 1994, there were no mental health nurses, psychologists, psychiatrists, or any real healthcare system, according to Darius Gishoma, mental health division manager at the Rwanda Biomedical Center. Today, however, Rwanda’s mental health system is internationally acclaimed, a model for decentralizing services and integrating community-based solutions.

The United States isn’t recovering from a genocide, but its mental health landscape is nonetheless dire, with one in five adults living with mental illness. Still, most Americans struggle to access care, since the U.S. only has 25,000 psychiatrists but needs 65,000 more, per a December 2023 report. And for those left out by the healthcare system, there’s limited community-based resources to find support, or prevent minor mental health conditions from spiraling out of control.

With its innovative, ground-up approach, Rwanda offers an instructive case study for how to address the American mental health epidemic, doing more with less.

Decentralizing mental health services

Rwanda is the size of Massachusetts but much more rural, with 82 percent of its population living outside urban centers. So, for the past 30 years, the government has sought to not only build up the mental health workforce but also decentralize this care—from the country’s five national hospitals to its more than 500 primary health centers.

Currently, mental health professionals staff 80 percent of these 500 centers, which ultimately helps improve access to care and patient outcomes, says Augustin Mulindabigwi, mental health director for Rwanda’s chapter of Partners in Health, a nonprofit providing healthcare in the poorest parts of the world. And for patients who still slip through the cracks, the Rwandan government and Partners in Health trained community health workers to identify mental illness symptoms and refer cases to these health centers, so far reaching 28 of Rwanda’s 30 districts, according to Gishoma.

Still, Rwanda doesn’t have enough specialists to meet the country’s burden of mental disorders, affecting over 20 percent of the general population and more than half of genocide survivors, according to a 2018 survey published in BMC Public Health.

“For instance, psychiatrists—we have only 16 in the country, which means basically one psychiatrist for 900,000 population,” Gishoma says.

As such, since 2012, Rwanda has trained primary care nurses and other frontline providers to deliver basic mental health care—a program called Mentoring and Enhanced Supervision at Health Centers (MESH). Specifically, experienced psychologists and psychiatric nurses run a five-day program for frontline providers, training them to provide basic psychiatric medications, therapy, and follow-up care, with weekly supervised visits for a year.

“Medicine is an apprenticeship, but people don’t have enough support to actually learn clinical skills,” says Stephanie Smith, a global health expert and psychiatrist at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, referring to the MESH program’s approach. “It’s not rocket science to have these very basic implementation strategies on how you actually deliver mental health care.”

Partners in Health rolled out the MESH program to three Rwandan districts by 2019, but last year, they trained healthcare providers from 46 new sites, with the goal of scaling up services across all of Rwanda’s primary health centers.

A similar kind of decentralization could be useful in the U.S., given that more than half of Americans live in regions designated as Mental Health Professional Shortage Areas. Turning mental health specialists into public health professionals offers a viable solution, Smith says. “How do you use these individuals to support a broader swath of the population,” she asks—instead of the model of the psychiatrist sitting in the hospital, “woe to anybody who can’t get in.”

This work has already begun in Massachusetts, where the Blue Cross Blue Shield Foundation funded five community-based organizations to have staff deliver therapy, following the same training model and psychological intervention originally deployed in Rwanda, says Smith.

Audrey Shelto, CEO of the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Foundation, has described how the state’s dire mental health crisis underscored the need for new options.

This pilot program aims to reimagine the role that less specialized individuals “can play in meeting the basic mental health needs of communities,” Shelto stated in a press release last year. “I’m not saying we can just farm out complex psychiatric problems to community health workers because that’s wrong and can’t happen in resource-limited settings either,” Smith continues. “But you can figure out what are the things you can address at the community level and really build that system.”

Emphasizing community-based healing

Mental illness, however, can’t be addressed through medical management alone, partially due to stigma, access concerns, and institutional distrust.

“When a person is being followed for mental health conditions, people think that person is useless, is a fool, is mad,” says Mulindabigwi. “They think this condition is not for modern medicine; let’s go to religious healers.”

Rwanda has thus sought to provide mental health support outside clinical settings, largely through a network of non-governmental organizations, says Gishoma.

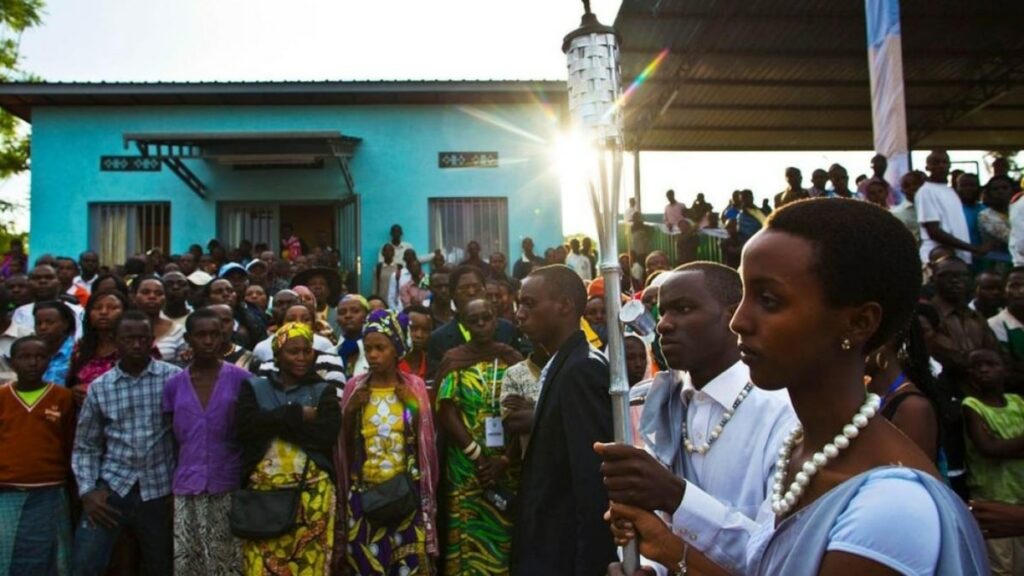

For example, GAERG is a genocide survivor’s organization that seeks to promote healing and resilience, from grouping members into “families” with a father, mother, and children, to hosting more than 600 community healing groups. “They need a safe space, whereby each and every one can hear the other and find solace without any judgment,” says Fidele Nsengiyaremye, GAERG’s Executive Director.

One such GAERG group meets at the Aheza Healing and Career Center, a few minutes away from the Ntamara Church, where 5,000 people were shot, bombed, and hacked to death.

“We had lost our culture; our minds were lost too,” says genocide survivor Munyankore Baptiste. “Among the support they gave us, the first was talking about our stories to ensure mental well-being. They brought back our light.”

Thirty years ago, Baptiste lost his wife and three kids but never went to the hospital to seek help, despite his depression, flashbacks, and nightmares. Aheza has provided Baptiste with a community to share stories and learn from other survivor’s coping strategies. He also loves the weekly yoga sessions. “I’m now 85 years old, yet I am still very strong—through yoga,” he says. “Those who used to walk slumped over are now standing straight.”

Similarly at the community level, the Rwanda Prison Fellowship runs a series of reconciliation villages, where genocide survivors and perpetrators live together—promoting recovery through shared testimony and ultimately forgiveness.

“When they have opportunities to share their stories of the painful past, people can have time to get relief, express emotions, and slowly build resilience,” says Felix Bigabo, a psychologist who coordinates these villages.

Niyonagire has seen this work firsthand, having fled Bugesera District when she was 21 years old, but resettling in the MBYO Reconciliation Village 11 years later. Here, with her kids, she lives alongside Xavier Nemeye, the man who killed her mother and sisters, among other perpetrators.

“I used to always feel like I was going to die, like I had no hope for living,” Niyonagire says. “After telling them that I had forgiven them, I immediately started feeling a sense of peace in my heart,” and her PTSD and suicidality ultimately subsided.

Beyond these collective healing efforts, a big part of mental health recovery is reintegrating patients into their day-to-day lives and giving them a sense of purpose. Partners in Health thus offers psychosocial rehabilitation services, or self-help groups, as part of the MESH program. They train patients with mental illness to make small handicrafts, raise livestock, or farm crops like rice and sorghum, providing start-up resources and empowering them to create small cooperatives.

“Interacting with others, they no longer feel useless,” says Mulindabigwi. “They feel dignified because there is something they’re involved in, and they’re trying to contribute to the progress of their families.”

Future of mental health

The U.S. has a far higher density of mental health specialists than Rwanda, but patients still struggle to access care in the one-size-fits-all model, with little decentralization or community integration. As such, many patients seek help for mental health only when they are in a crisis, their conditions severely exacerbated and much more difficult to treat.

But in Rwanda, the country has developed a suite of tiered services to meet patients where they are, whether it’s Ndera Neuropsychiatric Hospital in the capital or the healing group just down the road.

These local support services can build trust within the community to triage severe cases to the hospital, while addressing other cases in their earliest stages.

“If we really want to reduce the burden of mental illness, then helping people who have that kind of moderate problems is really important,” says Smith. “How do you bring care closer to communities and where people are? I think we could learn a lot from that in the U.S.”

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : National Geographic – https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/rwanda-mental-health-30-years-genocide