Claire Panosian Dunavan is a professor of medicine and infectious diseases at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and a past-president of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

Did you happen to read the recent report about six Americans who ate grilled kabobs containing coiled nematode larvae? Looking back, the ruddy barbeque served at a gathering of relatives from Arizona, Minnesota, and South Dakota came from a black bear harvested in Saskatchewan. Following its slaughter, the meat was frozen for 45 days. The bear meat was then inadvertently undercooked because “it was difficult for the family members to visually ascertain the level of doneness,” the CDC wrote.

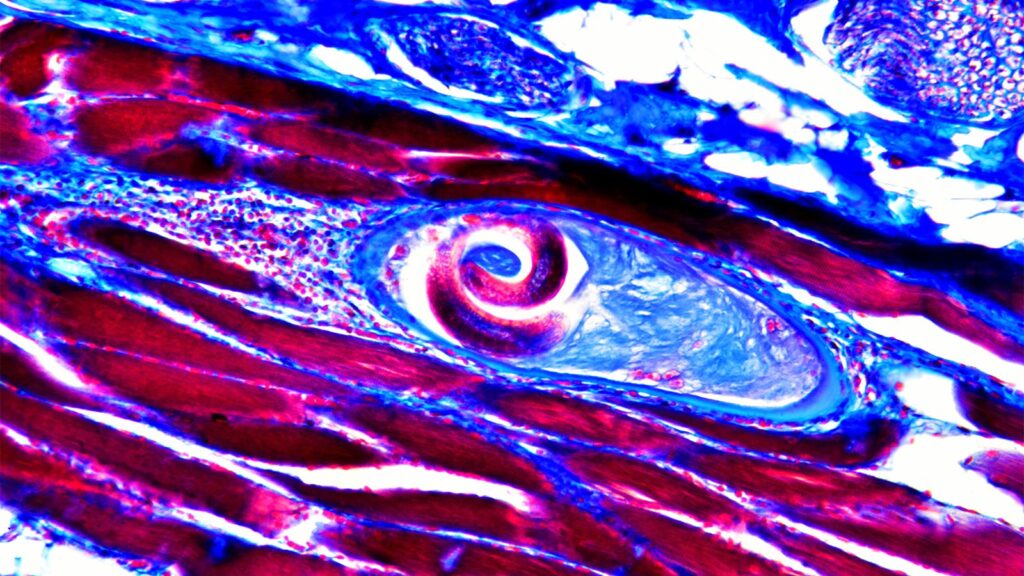

Studies of some still-frozen meat later revealed live, motile larvae. Meanwhile, molecular tests confirmed that the bear’s perp was Trichinella nativa, an arctic and sub-arctic species whose muscle-invading juveniles can survive sub-zero temperatures, sometimes for several years.

Now to the afflicted humans. The index case was a 29-year-old man who was twice hospitalized with classic features of trichinellosis: abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, myalgia, periorbital edema, and a high white blood cell count (in his case, it was 27,000/ml) along with Trichinella’s signature eosinophilia. Others who ate the meat were also ill enough to be hospitalized. And we can’t forget the two individuals who declined to eat the kabobs but consumed grilled vegetables — they were mildly symptomatic, likely due to cross-contamination during cooking.

The story scored media buzz, and it also underscores a disturbing fact: today, certain Americans’ appetite for exotic meats — bear in particular — is fueling flurries of an invasive, food-borne blight that was once mainly linked to pork.

“When opportunity knocks, go for it!” is a concept I like to embrace. Ergo, what better time than now to appreciate our country’s (largely) successful elimination of Trichinella from pork along with the parasite’s ongoing threat both here and abroad? But first, let’s give credit where credit is due.

“Sandy Diaphragms” Past and Present

As many readers know, Sir James Paget was an English pathologist who discovered an osseous disease in which fragile, misshapen bones produce pain, inflammation, and fractures.

But perhaps that’s not all he should be known for. In 1835, while still a medical student performing an anatomic dissection, Paget wondered why the cadaver’s diaphragm contained “an immense number of minute whitish specks.” He then excised a fragment of the muscle and, using a simple hand lens, noted a “peculiar animalcule” resembling an encapsulated worm within one of its many calcifications. Nonetheless, scholarly acclaim for scrutinizing what was then called a “sandy diaphragm” fell not to Paget but Richard Owen, an assistant curator at the Royal College of Surgeons who published a seminal report that barely mentioned the student.

Thirty years later, the omission led to a heated debate in The Lancet about Trichinella’s true discoverer, from which the then-eminent Paget wisely and graciously abstained.

What also came of Paget’s early scientific zeal was a new method of assessing prevailing rates of human trichinellosis. Between 1935 and 1941, for example, a survey of autopsied diaphragms from more than 5,000 deceased Americans found that one in six had at one time suffered the infection. In contrast, by the late 1960s, the percentage of Trichinella-positive diaphragms was down by a whopping 75%.

This brings us to further facts about the parasite and modern reforms in the care and feeding of pigs that led to declining rates of infection.

Trichinella’s Principal Culprit

The genus Trichinella (formerly Trichina, from thrix, the Greek word for hair) is now known to include 10 distinct species of tissue-invading roundworms that favor carnivores ranging from bears to boars to cougars to walruses (all of which, as it happens, have produced recent infections in humans) in addition to dogs, horses, reptiles — you name it.

Nonetheless, Trichinella spiralis has always been the principal species plaguing swine, which, in turn, account for the vast majority of human infections. And since pigs are famously omnivorous, the real problem as recently as the mid-20th century was the lack of regulation around their consumption of other carnivores, including their own kin.

Today, we should be thankful that many countries, ours included, dictate far more stringent conditions for modern pork production: rat-free facilities (since rodents can also transmit Trichinella); garbage-cooking laws; pure, grain-based diets; and prohibitions against including animal waste in feed. Meat and slaughter inspections have also played a role, as well as newer breakthroughs such as pooled-sample testing of porcine tissue digested in acidified pepsin and serologic surveillance of pigs. Simply stated, government oversight plays an important role in guaranteeing that our pork is wholesome and safe.

At the same time, there’s no law against keeping and harvesting a backyard pig. Or hunting and eating boar or cooking up some bear chili. Or taking a chance on an enticing, high-risk dish in a far-away place. What else can I say? Sausage and larb lovers, please take note.

Consumer Takeaways

In recent years, what some might call adventurous eating has captured our imaginations. Many of us, myself included, are unabashedly intrigued by new, exotic tastes and fare from land and sea.

So the final challenge this poses, especially in light of our exponential growth in knowledge about foodborne infections, is to empower the public with better education that combines key facts and engaging stories.

Of course, it makes sense to stress proper cooking of meats (and using a thermometer, for God’s sake) to assure items reach temperatures that will kill Trichinella larvae and other hidden invaders.

But what’s the point in preaching that if even seasoned professionals don’t always follow the advice or at least share their own (potential) misadventures? I too have a vignette that may surprise you. At a party a few years back, my husband and I enjoyed some deliciously seasoned boar-burgers served up by a long-time medical friend who is also a serious hunter.

“Boar?” you may be asking yourself now. “Can’t they carry Trichinella parasites due to their natural habits of cannibalism and predation?” Well, yes. But, in this case, I reasoned, the mixture was definitely well-cooked and, prior to that, had been frozen. Which brings us back to the barbecued bear fiasco…

A key difference here: unlike Trichinella nativa, Trichinella spiralis and other Trichinella species that sometimes infect boar are not freeze-resistant. So, needless to say, no one eating our pal’s burgers got sick.

Sometimes when making decisions about what’s safe to eat, those little bits of knowledge make all the difference.

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : MedPageToday – https://www.medpagetoday.com/opinion/parasites-and-plagues/111178