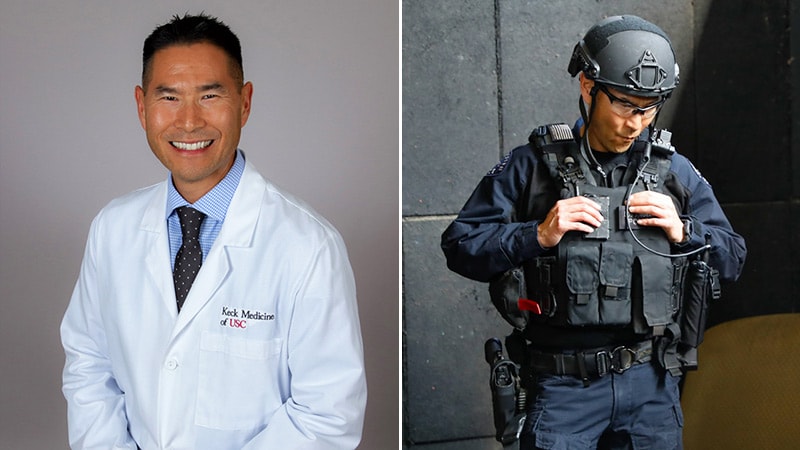

Physicians often wear a number of hats — specialist, academic, researcher, and clinician. But few wear different uniforms. Kenji Inaba, MD, FACS, FRCS, chief of the Division of Trauma, Emergency Surgery and Surgical Critical Care at the Keck School of Medicine at USC, Los Angeles (LA), California, routinely swaps his scrubs and white coat for black and blues. Yes, the top trauma surgeon at one of the nation’s busiest hospitals moonlights as a police officer with the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD).

You might wonder…how?

How can these two careers be compatible? How can a trauma surgeon and department head find the time (or desire) to train as a cop and patrol the streets of LA?

As unconventional as it sounds, Inaba has dedicated himself to making this marriage of medicine and policing work. His reason is simple: He grew up in a family that believes if you can help others, you should.

Not that simple means easy, of course.

A Journey Toward a Badge

The intersection of the LAPD and medicine dates back to the late 1880s. Then, a single Police Surgeon tended to police officers and crime-related victims in a two-room emergency unit in the back of the downtown Central Police Station. In 1927, the Georgia Street Receiving Hospital, Los Angeles, California, opened, providing LAPD officers with a full staff of doctors and nurses, including a chief surgeon. Over the years, that position shifted into the role of the LAPD medical director, who oversees a team of medical technicians and provides regular training to officers.

Inaba first became aware of the LAPD medical director opening early in his career at Los Angeles County Hospital, Los Angeles, California. He was interested in using his skills to support the officers and their families but couldn’t make the time commitment. “They wanted me to go through the training at the Academy and serve as a sworn police officer,” he recalled. “And to be honest, there was no way I could do it as new faculty.”

A decade later, after settling into his career as professor, researcher, consultant, and surgeon, Inaba felt ready to take on the challenge of the LAPD medical director position, as long as his partners were on board. Police Academy training takes place every weekend over the course of 18 months, which meant that Inaba’s partners would have to be willing to cover his weekend calls during that entire period. They were, and in 2016, Inaba completed his training and was sworn in as a reserve officer.

That was enough for Inaba to become the medical director, but he discovered that he deeply enjoyed the work. “I really gravitated toward it — the people, the job, being able to help people,” he said. So, he made the unprecedented move to complete a 400-hour probationary period to become a full-fledged LAPD patrol officer.

Upon completion, the then outgoing chief of police, Charlie Beck, reinstated the role of chief surgeon and appointed Inaba in June 2018, stating in a notice that he would “serve as the primary coordinator of emergency medical programs for officers injured in the line of duty and emergency medical and first aid training programs for LAPD personnel.”

From Family Medicine to Gunshot Wounds

Inaba describes his role in the department as an advisor to the chief of police and command staff on all things medical. “That can be policy-type issues,” he said, “but we have officers that get cancer or their kids get sick. We help our officers and their families negotiate critical illnesses. Sometimes it just helps to talk through what it is that they’re going through and take the time to explain the diagnosis and the treatment choices.”

Inaba also trains officers on how to best respond to medical emergencies, as they are often first on the scene. “They can operate in that ‘hot zone’ where traditional EMS partners cannot enter safely,” Inaba said. “We want the treatment to happen immediately at the point of injury, as soon as the situation is safe enough to proceed, even before our EMS partners arrive.”

This includes tending to fellow officers injured in the line of duty, which Inaba said, “happens all the time.”

“Without Kenji providing that training, I don’t know where I’m at,” said LAPD officer Steve Wills in an interview with KCAL News, a CBS News affiliate. In 2023, Wills was wounded in a shootout and struck in his left arm and right leg. Two officers pulled him to safety, and a team member began treating his leg wound by driving his knee into Wills’ upper thigh to stop the bleeding — a result of Inaba’s training. “I owe all of them my life,” Wills said. “That’s a level of gratitude I can’t verbalize and a debt I can never repay.”

When these tragedies strike, Inaba races to meet injured officers and their families at the hospital to provide any additional support they may need.

A Family Tradition of Service

For Inaba, the question of why he takes on this additional role is much easier to answer than how he does it.

“Growing up, the act of volunteering was very important in my family,” he said. Inaba’s father left Japan to come to the United States to earn his PhD in chemistry from Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, following World War II. Afterward, he relocated to Ottawa, Canada, where he spent a great deal of time advocating for the Japanese Canadian population. Inaba recalled that when his father was moved into a nursing home, things that commemorated the volunteerism he’d done over the years occupied all of his limited wall space.

“It’s an example he set,” Inaba said.

Inaba and his medical partners devote time to working with disadvantaged communities in LA — everything from providing basic healthcare to removing tattoos from former gang members. When devastating earthquakes hit Haiti in 2010 and Nepal in 2015, they rushed to provide medical support. A number of partners also traveled to Ukraine in 2023 to tend to the injured and provide tactical and emergency medical training. “It’s a really important part of our practice here at USC,” Inaba added.

And Now…the How

How Inaba manages his time and has the bandwidth to sustain two (three? four? five?) careers requires a complex planning system and a seemingly endless amount of energy.

He plans his calendar in 4-week increments. First, he inserts the three to five 24-hour calls as the base. Then he’ll fill in the hospital administrative requirements for his numerous roles. After that come the mandatory days for police officer training, such as firearm qualification days once every 4 weeks and mandatory emergency medical technician training days. “Then around that, I build anything else that’s required, which varies,” Inaba said.

In addition to 6-hour patrol shifts, Inaba encounters last-minute emergency tasks, like supervising the transportation of a high-risk, high-profile inmate from a West Coast hospital to an East Coast prison. “They need a physician who can work within that system, who can be armed and fly alongside this prisoner back into the federal system,” Inaba said. “There are very few people who can do that, so we have a whole task force.” These assignments can take up multiple days with little advance notice.

There’s also the essential time for Inaba’s family — a wife and son whom the department helps to keep private for security reasons. Together, they make time to travel and enjoy the outdoors, especially skiing and mountain biking north of the Canadian border, both of which Inaba used to race competitively. He also is a medical consultant for the popular TV series Grey’s Anatomy, proofreading every script for the past five or six seasons — in his “spare” time.

The Rewards — Medical and Personal

Inaba ultimately feels he gains as much as he gives, finding ways to use one experience to inform the other in meaningful ways. For instance, his LAPD field experience has helped to inform his academic research.

“One of the things that I’m very interested in is the situation of the active shooter in the hospital setting,” he said. Inaba was part of The New England Journal of Medicine article that addressed the topic of an active shooter inside a hospital and what can be done to prepare.

As a police officer interfacing with the Rampart Division of LA County that serves communities to the west of downtown LA, Inaba said he’s gained important insight on how people live. “It really gives me a deeper understanding of the social context that our patients are from,” he said. “As a surgeon, this really changed my approach to how I set people up to go home and when they’re ready to go home. Some things like packing a wound, for example, are just not possible. We may say, ‘Shower and pack this wound a few times a day’, but they might not have a shower or access to clean running water.”

He’s also gained a greater understanding of work-family relationships among police officers. “I love my medical partners. But I recall an incident when I was a very young probation officer, and my partner literally stepped in front of someone who had the potential to harm me. That’s a very interesting partnership/family,” Inaba said.

To most people, Inaba’s time management and energy may seem superhuman. But for him, it all comes down to everyone being willing to give what they can, when they can.

“It’s very important to me that everyone do something to use the skills that they have to help others without being compensated for it,” he said. “It’s something I tell my residents and fellows every single day. We can all afford the time to give something back to the community.”

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : Medscape – https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/wildest-side-gig-meet-trauma-surgeon-whos-also-cop-2024a1000crk