The VBS Mutual Bank scandal that broke in 2018 hit the papers again this week with the news that auditor KPMG had signed a R500-million out-of-court settlement with the liquidator, Anoosh Rooplal.

Before Daily Maverick broke the quantum of the settlement (confirmed by a source close to the matter), Cosatu was scathing in its criticism of the “veil of secrecy”, saying it was a disservice to the countless workers and residents of municipalities who suffered because of the financial mismanagement and corruption at VBS, which KPMG, as the auditor, failed to prevent or expose.

Daily Maverick took a closer look at who was involved in the scandal that led to losses of more than R2-billion, and who has been held accountable in the six years since.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Confidential out-of-court settlement between VBS and KPMG was R500m: source

The bank was placed under curatorship in March 2018 and the first tranche of liquidation dividends was paid out early in 2022.

“A first liquidation dividend of seven cents in the rand is being paid to all proven concurrent creditors. This amounts to approximately R159-million, of which [about] R110-million will be paid to relevant municipalities,” said Rooplal.

Creditors who lodged valid claims included 13 municipalities, various business depositors, retail depositors and supplier creditors. However, retail depositors (the average person in the street) who had more than R100,000 of their money in VBS were paid up to R100,000 in 2021, from the South African Reserve Bank guarantee.

Of the original 18,300 deposit accounts, 17,750 were transferred to Nedbank at a value of R260-million, and 98% of the R260-million was activated and collected by depositors in terms of value. On 9 July 2018, the South African Reserve Bank announced that it would facilitate the repayment of all retail deposits up to R100,000 per retail depositor, starting from 13 July 2018 for the next three years.

Preferential creditors included former employees of VBS Mutual Bank. Rooplal said the 26 employees received a final settlement of up to R28,000 each.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Outcry after KPMG signs ‘confidential’ settlement with VBS Mutual Bank liquidators

Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) deputy president Floyd Shivambu during a media briefing on allegations that EFF and Shivambu benefitted from the VBS bank looting, 6 October 2018, Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Sowetan / Thulani Mbele)

Brian Shivambu. (Photo: X @BrianShivambu)

Where did the money go?

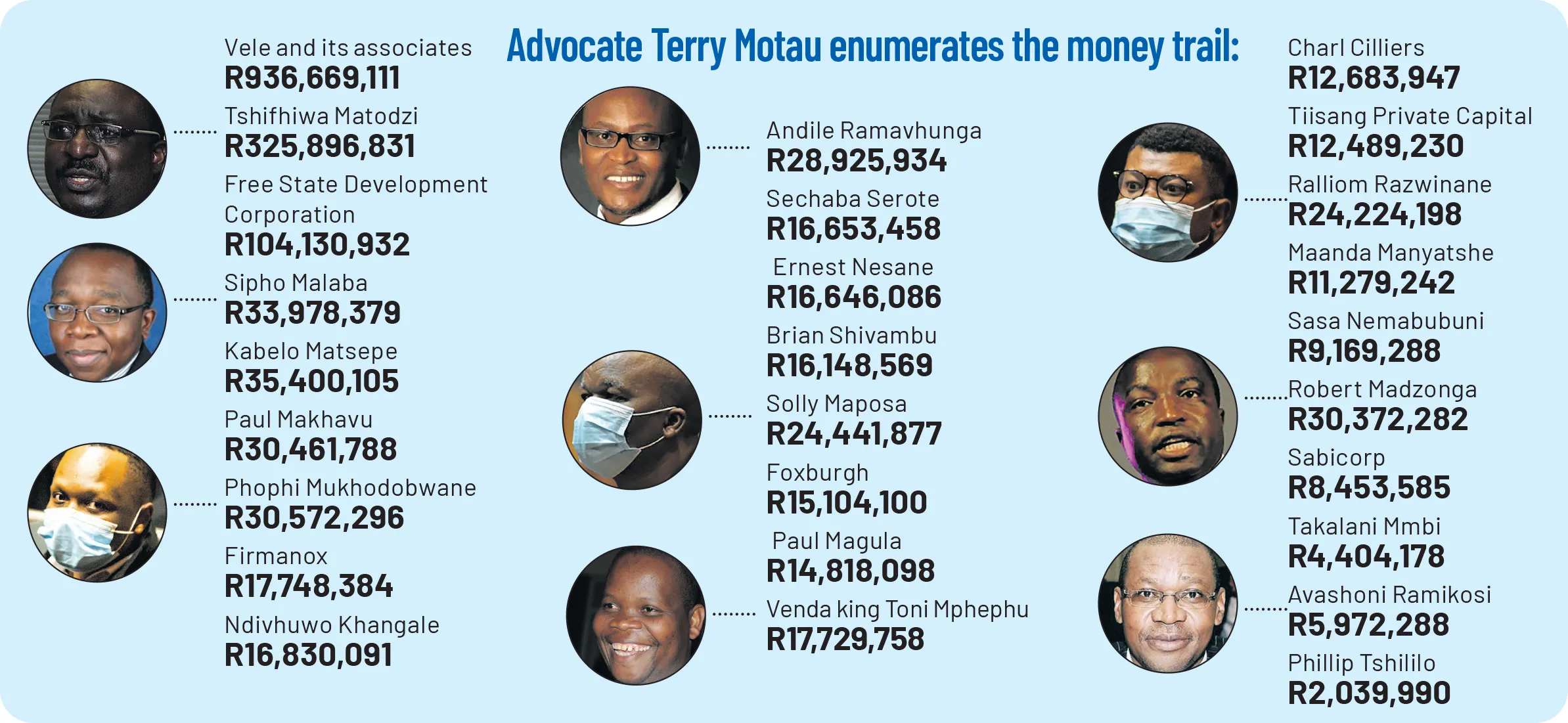

According to a report by Advocate Terry Motau and Werksmans Attorneys, compiled for the SA Reserve Bank from the forensic accountants’ report, R1,894,923,674 was gratuitously received from VBS by about 53 persons of interest, both natural and juristic, over the period 1 March 2015 to 17 June 2018.

EFF deputy president and MP Floyd Shivambu was found guilty of failing to declare a payment of R180,00o received from his brother, Brian Shivambu. Floyd was found guilty of breaching Parliament’s code of ethical conduct and was docked nine days’ salary.

Who was held to account?

By November last year, 32 people had been arrested. The most recent arrests late last year were those of Lepelle-Nkumpi Local Municipality’s former municipal manager, Thabo Ben Mothogoane; and its former chief financial officer, Rosina Mangaka Ngoveni; as well as Thapelo Molatlhegi, director of STG Financial Solutions.

Although at least 32 arrests were made by November last year, very few have been sentenced. The most high-profile sentence to date has been Phillip Truter, the former chief financial officer of VBS. He took a plea bargain of seven years’ imprisonment and agreed to turn state witness.

In July 2022, businessman Keaobaka Kgatitsoe was handed a five-year suspended sentence and ordered to pay R460,000 for money laundering linked to fictitious invoices submitted to VBS Mutual Bank.

In October last year, former Thulamela municipal manager Hlengani Maluleke was also handed a five-year suspended sentence for his role in the approval of an unlawful investment of municipal funds in VBS.

The Independent Regulatory Board for Auditors (Irba) fined Dumisani Tshuma R200,000 after it found he was guilty of misconduct for failing to disclose his interest in VBS.

Sipho Malaba, the partner at KPMG who approved and signed off on irregular financial reports, was suspended in 2018. He was arrested in 2020 and will appear before Irba for a disciplinary hearing later this year. In his report, Motau recommended that Malaba be criminally charged and revealed that VBS had given Malaba “soft” credit facilities of almost R30-million.

Ihawu Lesizwe was a company owned by Malaba’s wife, Jacqueline, and the company had several vehicle finance facilities, a mortgage bond and an overdraft facility on a classic business account with VBS. Malaba and his wife were signatories on all these facilities and their home in Fourways was financed by the VBS mortgage bond.

The VBS corruption trial that kicked off late in 2022 has yet to be concluded, with the next date set for 6 May. Justice may be a long time coming. Markus Jooste, the man at the centre of the Steinhoff scandal, has yet to see the inside of a courtroom more than six years later. Although he was up for two charges of fraud in Germany, he failed to show up in the German court in April last year.

Phillip Truter, the former chief financial officer of VBS. (Photo: VBS 2016 Annual Report)

Who suffered the most?

While the numerous officials involved in the massive VBS corruption were living large on their ill-gotten gains, the victims have a different story to tell.

Madambi Muvhulawa, who was one of the founding directors of VBS bank, feels betrayed by his colleagues, some of whom are now facing criminal charges for stealing money from the bank, which has now collapsed. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba / Mukurukuru Media)

Played for a fool

Madambi Muvhulawa doesn’t mince his words when expressing his feelings about the betrayal by fellow directors who are accused of playing a role in defrauding VBS Mutual Bank – eventually leading to its demise.

“It’s always in my mind [events leading to the bank’s collapse] that, you know, I was played for a fool while sitting in the very board with people that I could trust, not knowing they were doing certain things underground,” Muvhulawa said this week from his home in Makhado in Limpopo.

He carries the even greater burden of facing people who, for many years, invested in the bank because he had personally advised and recruited them.

“Facing our people, poor people, some of them have died, some have put all their pensions in the bank – even health-wise, I have been affected,” he said.

Muvhulawa joined VBS as a director when it was established as a building society by the Venda apartheid homeland in 1982. He has been fighting to save the bank and people’s money. He only learnt about the latest developments in the media.

At 86, he is too exhausted to run up and down trying to resolve the intricate issues of a bank that was once the pride and hope of his people, and that has now become a source of pain for many who lost their life savings.

Nyawasedza Raphunga holds up her VBS Mutual Bank savings book. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba / Mukurukuru Media)

According to the Public Investment Corporation, “the purpose of the investment in VBS was to support the provision of financing to sections of society who were historically disadvantaged and to achieve a high social impact”.

As a result of apartheid legislation, black people, especially those living in the homelands, had no title deeds to the land they occupied. This denied them an opportunity to provide surety when applying for loans and general financial assistance.

“We filled that gap,” said Muvhulawa.

Later, the building society was upgraded to a mutual bank, which meant it could provide more products and services. In the 2000s, the bank applied for a licence to trade as a commercial bank.

While the application was still under review, municipalities, allegedly under instructions from the ANC, invested billions of taxpayers’ money in VBS. However, this was against the Municipal Finance Management Act (MFMA), which prohibits state entities from investing in mutual banks.

Muvhulawa said new shareholders were introduced under the umbrella of Dyambeu Investments, which had the support of then Venda King Toni Mphephu Ramabulana.

The Government Employees’ Pension Fund held a 27.63% share in the bank, Vele Investments held a majority of 58.85%, Dyambeu Investments held 4.60% and 8.93% was in the hands of others.

“As it was growing, some young people were brought in through Dyambeu [Investments]. These young people came in and they hijacked the board through voting out the old existing board members.

“I was the only one left and had to work amongst them. I was not happy with the way they were operating … but there was nothing I could do,” he said.

As hundreds of millions flowed in from municipalities, Muvhulawa believes this is where things started to go wrong.

“I think these young guys now saw a chance of manipulating the transactions for their own benefit,” he said.

Muvhulawa said that, during the time when Dyambeu Investments introduced new products such as vehicle finance and business loans, he was worried that “some of the things that were approved there were not approved satisfactorily”.

He said loans involving large sums were approved without proper checks.

In April 2018, a parliamentary portfolio committee meeting heard that National Treasury had sent an email in August 2017 telling municipalities that the MFMA did not allow funds to be deposited with a mutual bank. Subsequently, it issued a directive that all municipalities needed to withdraw their funds from VBS. Muvhulawa said this was the beginning of the end for the bank.

After the bank’s liquidation, Muvhulawa and others formed a forum to try to save the institution and help depositors to recover their money. In the process, he became used to receiving calls from concerned investors.

“Criminal cases are taking too long. Justice delayed is justice denied…

“I’m part of those who suffered financial losses. I started investing in the bank when it started,” he said.

The killing of two unionists and an ANC councillor who called for justice in the VBS saga seems to have sent shivers through depositors. But Muvhulawa said he has no fear and all he wants is to see everyone who put money in the bank being paid out.

“[VBS] was the pride of Venda; it was my pride. We started something that had never happened in South Africa. This was my life. I feel a void.”

Robert Livhoyi started depositing his money into VBS in 1997. The bank helped him build his home in Dzanani through a loan and also helped to suport his business ventures, which included the development of a shopping centre. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba / Mukurukuru Media)

Collapse shook the faith of a trusting customer

Robert Livhoyi started investing a good portion of his earnings as an entrepreneur in VBS Mutual Bank in 1997. A year earlier, he had quit his job to run a printing company in Dzanani, about 35km from Makhado in Limpopo.

Among his investments in the bank was a monthly stop order of R10,000. Later, he invested in a VBS share scheme and also got a R600,000 loan to develop a business property. “That bank was powerful,” said Livhoyi, adding that he built “a very strong relationship” with it over time.

VBS was attractive to most depositors and investors because it was easily accessible to rural folk and catered for communal organisations such as stokvels and burial societies, among others.

“It was a very simple bank and easy to deal with,” said Livhoyi, who built his home in Dzanani with a R180,000 loan from VBS.

Later, it extended other loans to help him to set up and grow some of his business interests, including the construction of a shopping centre in Musina.

Livhoyi, the secretary of a forum that is trying to save the bank and help investors to claim back their money, said despite red flags something was amiss at VBS, he never believed he would lose his investments.

“It was like a dream. I was dismissing the stories. I was always positive,” he said.

A few years before VBS’s collapse in 2018, it went on an expansion spree and opened branches in other parts of South Africa.

“I thought the bank was growing,” Livhoyi said. Around the same time, he was approached by one of the board members now implicated in the criminal case against the bank’s directors to become a member of the board. But he refused.

“If I was there, I’m sure they would have killed me because I would have never allowed that [mismanagement and looting to happen],” he said.

Livhoyi only became convinced there was something amiss when he saw media reports of customers sleeping outside VBS’s branches in Sibasa, Limpopo, in an attempt to withdraw their money.

But even then, he didn’t join the scramble because he thought he would get his money back.

The businessman, who invested a substantial amount in VBS, lost most of it. He was paid R100,000 after its liquidation, like most depositors did. Although he won’t say how much he lost, he seems to have accepted his losses.

“Losing money affected my dream [of building a mall] in Musina, but money can’t destroy me. I believe in Jesus. My faith [helped me] through the loss,” he said.

“[The accused] going to jail is not going to bring back the money. What we want to see is the bank being revived.” – DM/Mukurukuru Media

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R29.

![]()

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : DailyMaverick – https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2024-02-03-vbs-mutual-bank-scandal-six-years-on-the-r2bn-fraud-the-r500m-settlement-and-the-plight-of-victims/