GAZA STRIP —

Life in Gaza is a numbers game these days, where you try to calculate the odds of surviving even the most mundane tasks.

Do you risk going out to find drinkable water, despite word of Israeli tanks up the road? How long can you stand in line outside a bakery before the drone circling overhead drops a missile nearby? Which neighborhood has shelter for you and your family, doesn’t have a Hamas member or tunnel nearby, and could possibly be spared the relentless bombing?

Since the the Gaza-based militant group Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack inside Israel spurred the bombardment inside the Palestinian territory, such calculations have become crucial.

Through voice recordings, messaging apps and phone calls over several weeks, our correspondent worked with Times staff writer Nabih Bulos to give a personal account of living in a place where nowhere feels safe. To protect our correspondent, The Times is not publishing their name.

An oasis in a desert of death

For the first days of the war, we didn’t leave home. We have a generator and solar panels, so we could power the fridge and charge phones. But the bombing started getting closer. And when the Israelis issued the order to evacuate on Oct. 13, we (seven family members) left for the south of the strip.

Conditions, though, were so bad, it was bahdala — a humiliating mess. None of the shelters had water, electricity, hygiene. It was overcrowded, and there were strikes on the area anyway, so we decided it was better to come back to our home in Gaza City. That was Monday, Oct. 16. We stayed for two days, left again to the south, then came back home once more that Friday, a week after the evacuation order.

The neighborhood was a ghost town. There’s the Arab Orthodox Cultural and Social Center, which had 150 displaced people, young and old. It was the only place with life in it. For my family, it was like an oasis in the middle of a desert of death. We went during the day to our apartment but we decided to sleep at the center at night.

When we got there, they gave us two mattresses — it was two per family, it didn’t matter how many family members you had. (They told us it was the first day they had received mattresses and pillows.)

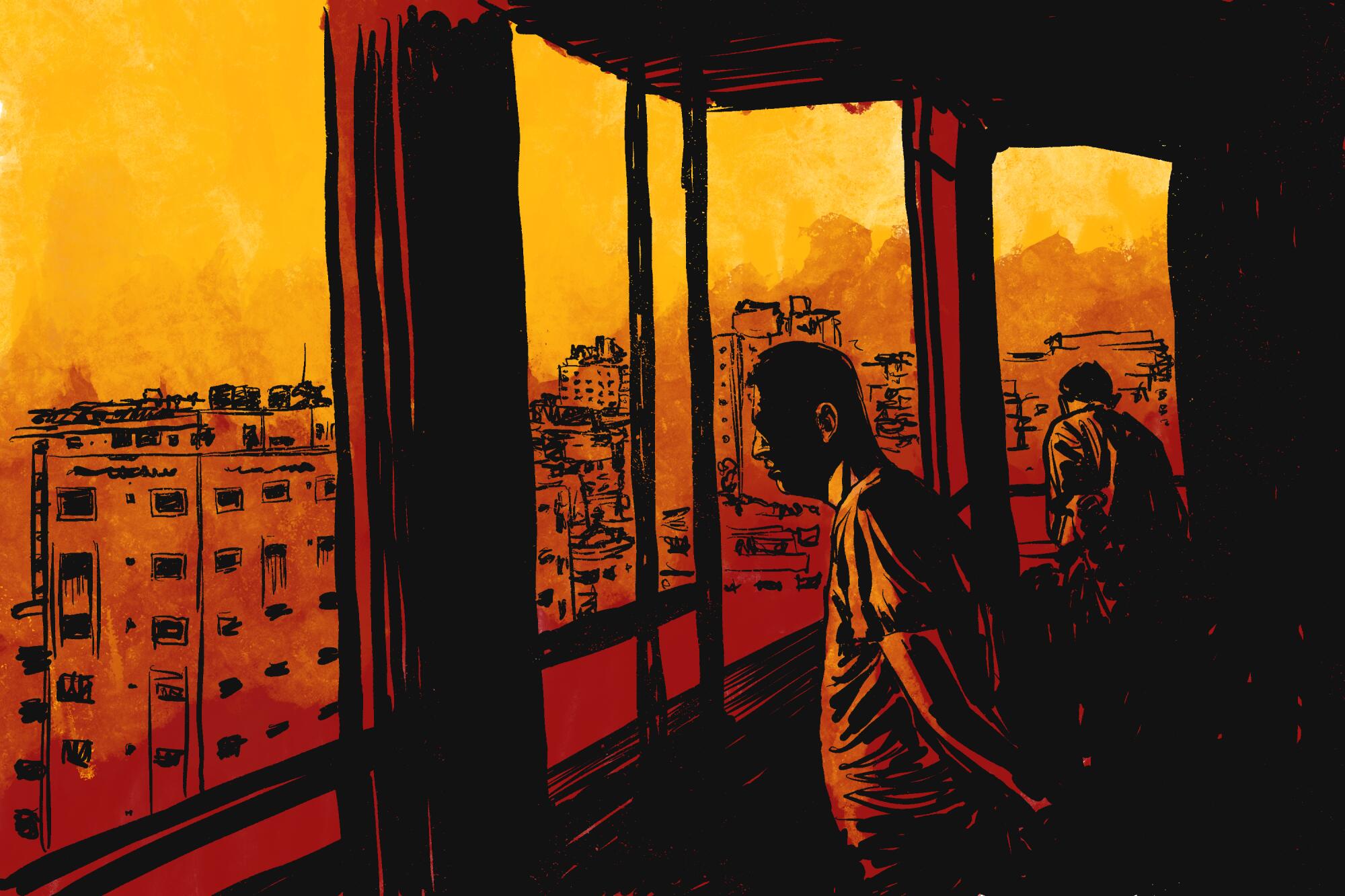

The whole sky turned to fire

(Illustration by Jim Cooke / Los Angeles Times)

At around 11 p.m., the bombing began. We were on the second floor. It was like something out of a movie — the windows had no curtains so we could see — and it was horrific: The whole sky turned to fire and the ground shook.

We first went to the staircase, all of us lined up and praying because of the shrapnel flying everywhere and the place shaking. When part of the wall fell on the stairs, we ran down to the basement and sat on top of each other there.

When the strikes continued, things got even scarier. Debris was hitting people, and we could smell gas. There was a nurse who was sewing up a woman’s head after she got hit with a piece of cement from the walls. It was chaos. I forgot I was a journalist. I was crying, screaming, praying and terrified.

We knew the center shouldn’t be under threat. At that point it had no evacuation order, and the zanaanas — drones — could see the place was full of refugees. The strikes finally stopped at 3 a.m., only to start again from 7 to 8:30. That morning, we felt like we were given a new lease on life. (I found out the center was hit directly two days later, after it had received an evacuation order.)

After that intense night, I managed to find a brave driver who brought us to the south of Gaza. We didn’t even stop home to get anything because there was shelling nearby. In any case, people still in the area told us that, although our building wasn’t hit, belongings in the apartment are destroyed because of the attacks all around it.

Someone flipped the ground upside down

As were driving south, I had a chance to see the situation. It was as if someone just flipped the ground upside down: Everything was shattered, every building either rubble or had every window shattered and roofs destroyed.

In the south, I couldn’t find anything to rent. It’s not a matter of money or that Gaza is small — people are afraid to rent to strangers, because you don’t know who they might be working for. There have been airstrikes on displaced people from Hamas who were wanted by the Israelis — and others nearby weren’t involved and still got killed because the attack was near them. People don’t want trouble, so they have a tendency to not rent to anyone coming from Gaza City.

In the middle of all this, we were lucky to have friends who let us stay in a new building in Deir al Balah that’s still under construction. We’ve been there since.

It has three rooms, but all seven of us sleep together in one room because we are afraid. It’s not perfect, but it’s a safe place where we can at least wash our clothes and brush our teeth.

Going back home is a bad idea. We need to get our things — the other day, I was thinking of getting fall or winter clothes and blankets because the weather is changing — but the area is getting more and more dangerous. Our neighborhood, everything there is gone. All the bakeries, all the supermarkets, even Care4, which was the biggest in Gaza City. No one can take the risk and return there before the war ends.

In Deir al Balah, things aren’t as available. It’s more of a rural area. There hasn’t been electricity here since the beginning of the war. At 5 p.m., the shops close and no one stays in the street. It’s safer, but still, bombings happen here without warnings. And because the buildings here are structurally weaker, the number of the dead increases.

(Illustration by Jim Cooke / Los Angeles Times)

One major problem in Deir al Balah is that there is no water. The other day, I don’t know how, I saw one guy distributing water, and I was able to fill up tanks for washing and even to shower. I also found drinking water, only these tiny 200-milliliter (less than 7-ounce) plastic bottles, but I bought a few boxes of them and we’re bartering them with our neighbors for nondrinking water when we need it.

Another issue is that there aren’t many bakeries operating; many were in areas hit by numerous airstrikes. And even when UNRWA — the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East — or other organizations give out flour, it doesn’t improve the situation enough.

Our routine now is that my mother wakes up my two brothers at 5 a.m. and they go to the bakery, because the line takes three hours, and even then you only get two shekels worth of bread each. Now you find people making flatbread. They can bake it on mud ovens, not necessarily something that needs gas or electricity. It’s irregular-shaped. People from the north of Gaza or the city, they didn’t know it before, but it’s OK; it’s bread.

At 10 a.m., there’s a cafe that opens. It’s very crowded, so I give my brother my phone to charge. When that’s done, I give him my laptop so I can alternate.

We looked for a fuel canister, but didn’t find any. It costs 300 shekels (about $76), more than three times the price in peacetime. I finally called a farmer friend nearby and he brought me one. We were able to make a galayet bandora — tomato and garlic stew — and fried eggs for lunch.

Before, I was getting internet from the customer WiFi connection from the bank near our apartment. Now, we sometimes connect through our neighbor’s Wi-Fi. We talk to relatives abroad, or just sit with the neighbors and hear about the people around us. They had relatives under the rubble yesterday; some of them were killed.

Bread and tanks

Every day, supplies are dwindling and prices going up. You can’t get any transportation. People are using cooking oil to power engines now.

But it’s better than being in Gaza City.

(Illustration by Jim Cooke / Los Angeles Times)

All the friends who stayed there can’t sleep because of the strikes. It was just terrifying when we were there, like the airstrikes were in the middle of the living room rather than the street outside.

When they hit something, everything around it goes down because they’re using fire belts to hit the tunnels. (“Fire belts” are Gaza residents’ term for multiple strikes hitting the same area.) But it seems clear it’s not working, because the streets are destroyed, but we’re not seeing any crater revealing a tunnel, at least in the streets I’ve been on.

A few days ago, when we went out to get bread in the morning, drivers told us that there were tanks on Salah al Din Street — the main thoroughfare running through Gaza City. It was was like a thunderbolt. How and when did they reach Salah al Din Street?

Still, a lot of people almost want the Israelis to get in and be done with the ground offensive. They believe that when it ends that means the war will also end. Maybe not, but that’s what they think.

At this point, it’s very bad here. No one can go back to Gaza City, and anyway there are no cars or vehicles available.

We just feel we’re surrounded.

Illustrations by Jim Cooke, based on video from our special correspondent and archival photographs shot in Gaza by Times photographer Marcus Yam.

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : LA Times – https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2023-11-05/gaza-diary-what-life-is-like-under-daily-airstrikes-blackouts-scarcity