Kyle Ellis was in a panic. Two FBI agents were at his Indiana apartment with alarming news: They said they had evidence that his best friend and roommate may have been involved in the mysterious disappearance and murder of a onetime girlfriend.

Days later, the agents made a proposal that was nearly as shocking: They wanted Ellis to confront his best friend with the evidence — and to wear a wire when he did it.

Ellis agreed, and his secret recording would play an important role in a case that had eluded authorities, helping convict Brodey Murbarger in the murder of Megan Nichols, 15, who vanished in 2014. Her remains were found three years later.

Murbarger, 27, who has denied the charge, was sentenced in January to 50 years in prison.

In Ellis’ first interview about the case, he told “Dateline” about his recorded confrontation and the dramatic end of a close friendship that he and Murbarger had spent years building in Fairfield, the small farming community where they grew up in southern Illinois.

Megan’s murder, he said, was the “ultimate betrayal.”

“He was being everything bad that we said we would never be,” said Ellis, 28.

Teenage drama in a small town

Ellis, who’s preparing to become a lawyer and lives in Fairfield, and Murbarger got close as high school freshmen. He said they were “very” similar — smart kids from a small, rural town who didn’t fit in with the farming families and wanted to get out.

Both earned straight A’s their senior year and were two of the students in a four-way tie for Fairfield Community High School’s 2014 valedictorian, Ellis said.

Murbarger had known Megan since grade school. She was outgoing and thoughtful — someone who thought of others first and wanted to make them laugh, her mother said.

Megan, who was a couple of years younger, reconnected with Murbarger in her eighth grade year and later in glee club — which Ellis said most likely magnified the animosity of what became a fraught relationship, because another girl whom Murbarger was seeing was also in the club.

Murbarger bragged about being with both girls, Ellis recalled.

The teenage drama that followed escalated when Murbarger — who had been spending more and more time with Megan — took the other girl to prom. When Megan’s mother, Kathy Jo Hutchcraft, forbade her daughter from seeing Murbarger, he showed up at their house anyway.

She told “Dateline” that he told her: “Look, you are way too controlling. You’re concerning me, and I think you need to be on medication.”

“I said: ‘Excuse me? She’s 15 years old. I can tell her that she can’t date you,’” Hutchcraft said.

Later, Hutchcraft said, Murbarger sent her a text message saying he had talked to a guidance counselor about her.

“They know what you’re doing to your child,” Hutchcraft said he wrote. “And I don’t want to get DCFS involved” — child protective services — “but I will if I have to.”

Hutchcraft said she didn’t respond.

Murbarger’s lawyer didn’t respond to requests for comment. His family declined to talk with “Dateline,” and the Wayne County Sheriff’s Office in Illinois declined to make Murbarger available for an interview after he was convicted.

Murbarger’s best friend, Ellis, said he wasn’t aware of the exchanges. To him, Murbarger had always been polite and respectful — “like a brother to me,” he said.

“My opinion of him at that time was that he was, at least deep down, a very logical person, a very smart person.”

Megan vanishes

In April 2014, Murbarger made a strange offer. He wanted to give Ellis all of his things — his guitars, video game consoles and motorcycle — in exchange for $3,000. Murbarger was sick of his family, he told Ellis, and he wanted to run away.

Murbarger could also be overly dramatic, Ellis said, and he didn’t believe his friend was serious. But the fantasy kept evolving, with Murbarger running away sometimes on his own and sometimes with Megan, Ellis said.

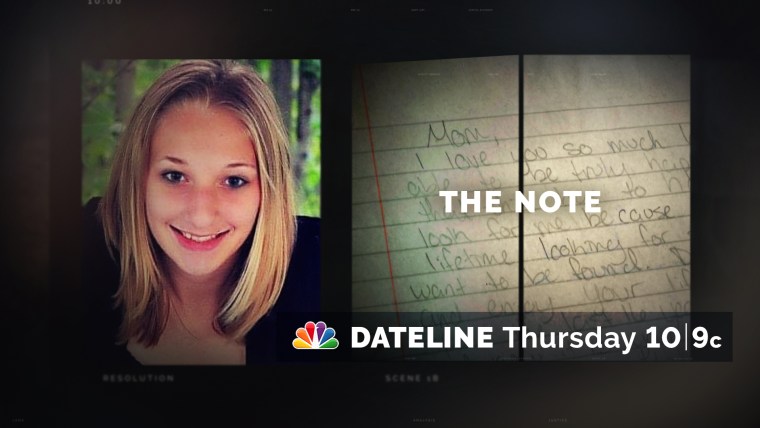

Three months later, on the night of July 3, Megan vanished. Authorities later discovered security video from two local banks showing her withdrawing cash from an ATM the day she disappeared. And her mother found ominous clues in her bedroom — a cellphone that had been wiped and a note telling her mother she loved her but not to look for her.

Ellis said that the next morning, when he learned the news, he immediately texted his friend — not to find out about what happened but to give him advice and see whether he was all right.

“I was concerned that he would be blamed unfairly for Megan’s disappearance,” Ellis said. “My advice to him was don’t talk to anybody without a lawyer.”

But Murbarger did, repeatedly, in the months and years that followed, providing an account of his whereabouts to the local police department and then, after the case was handed off a year later amid sluggish progress, to the Illinois State Police.

He told officials that he gave Megan an iPod the night she disappeared and that he drove around trying to find her after he learned she was missing, said Keith Colclasure, the Fairfield police chief who interviewed Murbarger days after Megan disappeared.

Ray Hart, the FBI agent who later investigated the case, said Murbarger’s account shifted over time, revealing inconsistencies and details that didn’t add up.

For instance, on the morning after Megan vanished, as her mother and grandmother frantically searched for her, they found Murbarger at home, washing his car.

“That’s a massive red flag,” Hart said, noting the strangeness of a 19-year-old’s cleaning his vehicle at 8 a.m. on July 4, hours after his girlfriend had vanished.

Murbarger told authorities he’d cleaned the car because he couldn’t sleep, Colclasure said. And when state police investigators field-tested a stain in its trunk, believing it could be blood, the results came back negative.

A key piece of evidence

The car — a 2009 Dodge Avenger — became key evidence after state police turned to the FBI for help.

In 2016, Murbarger wrecked it. Ellis — who by then was living with Murbarger in Evansville, where they attended the University of Southern Indiana — recalled his roommate saying he’d been involved in a single-car crash: He’d passed out while driving to his parents’ and veered into a tree.

He was floored when Hart, the FBI agent, showed up two years later with critical new information about the car.

A stroke of luck had allowed Hart to track down the Avenger. After the crash, it was sold to a salvage yard, which then sold it to a Missouri couple, who allowed the FBI to conduct more extensive testing on the trunk, Hart said. The couple agreed to the testing without a warrant, which wouldn’t have been possible to obtain because of how much time had passed since Megan disappeared.

The tests confirmed that the stain was Megan’s blood, Hart said.

“I’m sure the color just drained out of my face, and the only thing I was thinking, like, the whole time they were talking was ‘oh, s—!’” Ellis said, recalling his first meeting with the FBI.

Putting on the wire

Ellis said he didn’t sleep for days. Fearing what Murbarger might do to others — including a new girlfriend Murbarger was seeing — Ellis met with the FBI again and agreed to help. When Murbarger left town for a couple of weeks, Ellis moved out — and he later planned a get-together to explain why he’d left so suddenly.

The FBI would be listening as he did. It needed Ellis, Hart said, because Murbarger was no longer talking to authorities without a lawyer, and officials wanted to see how he’d respond to the new evidence.

“He was clearly nervous, but Kyle is certainly motivated by the right thing,” Hart said.

On July 2, 2018, Ellis made the case the FBI had made to him, telling Murbarger that the blood the agents had found was Megan’s, according to a transcript of the conversation obtained by “Dateline.”

“Why is her blood in your car?” Ellis asked.

“That’s a good question,” Murbarger replied. “I would like to know that, too.”

When Ellis pressed him, Murbarger again denied knowing anything about it. And when Ellis asked whether he’d killed her, Murbarger responded: “I did not kill Megan.”

Murbarger repeatedly denied having killed her during the conversation, but at one point he offered what Hart said was the closest thing to a confession he would be likely to give.

Ellis had asked about Megan’s autopsy. Her remains had been discovered a few months before, in a shallow grave in a rural area south of Fairfield, and authorities concluded she had most likely been strangled or suffocated, Hart said.

Murbarger said he wouldn’t have been able to carry out such an act. Then he began describing his state the day before Megan disappeared: He’d barely slept, his dog had died, he’d eaten little, and he’d accidentally backed into a woman’s car at Walmart.

“I probably couldn’t even have lifted my own body weight, much less strangled — if someone with anger issues found out about something and strangled her,” he said.

Ellis described the exchange as a “pin drop moment.”

Ellis had always known Murbarger to be a smart, polite person, but he had another side — one that seemed fueled by anger and control and that responded badly to disagreements, Ellis said.

Murbarger’s comment didn’t amount to a confession, Ellis said, “but it was pretty close.”

Investigators had suspected all along that Murbarger had strangled Megan in a fit of rage, and when his trial began last year, prosecutors presented the theory to a jury. As Ellis watched jurors deliver a guilty verdict, he was relieved that justice had been served. But he still finds himself dwelling on his onetime friend, evaluating day-to-day situations as Murbarger would have.

“I was around him for so long that he’s kind of a voice in my head,” Ellis said. “But I would like for him to not be anyone in my life now. I’d kind of like for him to not exist.”

Tim Stelloh

Tim Stelloh is a breaking news reporter for NBC News Digital.

Sergei Ivonin

Sergei Ivonin is a producer for NBC News.

Kimberly Flores Gaynor

contributed

.

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : NBC News – https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/illinois-teen-vanished-megan-nichols-brodey-murbarger-murder-rcna102611