Singapore

CNA attached 12 trackers on recyclable items and placed them in blue bins around Singapore to see where they ended up.

CNA attached trackers to recyclable items and deposited them into recycling bins around Singapore. (Photo: CNA/Try Sutrisno Foo)

New: You can now listen to articles.

Sorry, the audio is unavailable right now.

Please try again later.

This audio is AI-generated.

SINGAPORE: Every week, housewife Veron Wong will gather up items that her family is done using, setting them aside to deal with in her free time.

The 54-year-old will then painstakingly separate the different materials – removing the cap from the milk carton for example – then rinse and dry off both.

Mrs Wong then lugs her week-long haul down to the void deck of her block in Punggol to place them into blue bins, or Bloobins, for recycling.

But just recently, she was confronted with a common scene – items jumbled in disarray, some of which were not suitable for recycling and some of which could contaminate items which could be recycled.

“I think we should give up on recycling, I look at the condition of the bin and how the items get mixed and drenched in the rain, I feel like I’m wasting my efforts,” the dismayed Mrs Wong said.

The recycling bin at the bottom of Mrs Veron Wong’s block in Punggol. (Photo: Veron Wong)

Mrs Wong is not alone. Others have been taking to social media to complain about the state of their recycling bins.

Earlier this month, someone posted photos on Facebook group Complaint Singapore of a recycling bin – apparently in Joo Seng Heights – that was full to the brim with junk. The garbage included Old Chang Kee food packaging and other items that belonged in the garbage bin. The person who shared the pictures said in photo captions that he felt his housing block’s residents were not ready for recycling.

Others who commented on the post described the mess as a common sight.

Such incidents also raise questions about how much of what is placed in the blue bins ends up being recycled.

A Facebook user posted photos of a junk-filled recycling bin to Facebook group Complaint Singapore on Mar 2, 2024. (Photo: Complaint Singapore/Chai Weilong)

For the environmentally conscious, knowing that the items placed in blue bins actually end up being recycled would go a long way to to instil confidence in the system and raise the recycling rate, those in the industry say.

Founder and CEO of green social enterprise Green Nudge Heng Li Seng said he is often asked about the fate of items placed in blue bins.

“They’re not very sure where the items really go to. And if they’re not very sure, they’re not likely to be convinced or willing to do the work (to recycle them).

“I think having a chance for consumers to continue to know where these items go and to feel assured that (they) continue to go to the right places does help to increase the willingness to do the work,” Mr Heng said.

National University of Singapore’s (NUS) Professor Tong Yen Wah went further to say that such reassurance is important so that people know it’s “not a waste of their time”.

With this in mind, CNA conducted an experiment to try to find out what happens to things that get placed in blue bins.

COMMINGLED SYSTEM FOR DECADES

For the past 20 or so years, households have been placing items that can be recycled into blue recycling bins without having to separate them by material.

Singapore’s three appointed public waste collectors – SembWaste, ALBA W&H Smart City and 800 Super Waste Management – then convey the items by truck to materials recovery facilities where they are separated. From there, suitable items are sent for further processing at recycling facilities.

The process has resulted in 60 per cent of items getting recycled, while the rest gets disposed of as they cannot be recycled or are recyclables that become contaminated, according to figures from the National Environment Agency (NEA).

Even so, domestic recycling rates have been on the decline – 12 per cent last year, the lowest in over a decade.

While figures for last year’s recycling rates are not yet available, NEA’s 2023 survey on household recycling found that 72 per cent of households recycle, up from 64 per cent in 2021.

It also found that a higher proportion of respondents are aware of common items that can be deposited into the recycling bins and chutes but that awareness has declined on things – such as unwanted fruit or vegetable parts and soiled plastic food containers – that should not be deposited into recycling bins or chutes.

An assortment of recyclables with trackers that have not yet been attached. (Photo: CNA/Try Sutrisno Foo)

TRACKING EXPERIMENT

Over a month or so, CNA put the household recycling process to the test by tracking recyclable items to see, as far as possible, where they end up after they are placed in blue bins at HDB void decks.

These items were: Four pieces of cardboard, four plastic bottles and four metal cans – all materials that are suitable for recycling. The items were cleaned beforehand.

To follow their movement, CNA secured a tracker to each item with tape which could be easily removed.

The 12 items were then split equally and deposited into six recycle bins in different locations across the island in December.

Two different items were placed into each of the six bins.

CNA ensured that the three public waste collectors were covered equally. That is, each public waste collector would collect from two bins with tracked items.

Over the course of the next few weeks, CNA then monitored the movement of the items on mobile tracking applications.

![]()

Tracked items placed around Singapore via an Android tracking app . (Screenshot: CNA/Koh Wan Ting)

Tracked items around Singapore via Apple’s Find My app. (Screenshot: CNA/Koh Wan Ting)

BREAKING DOWN THE RESULTS

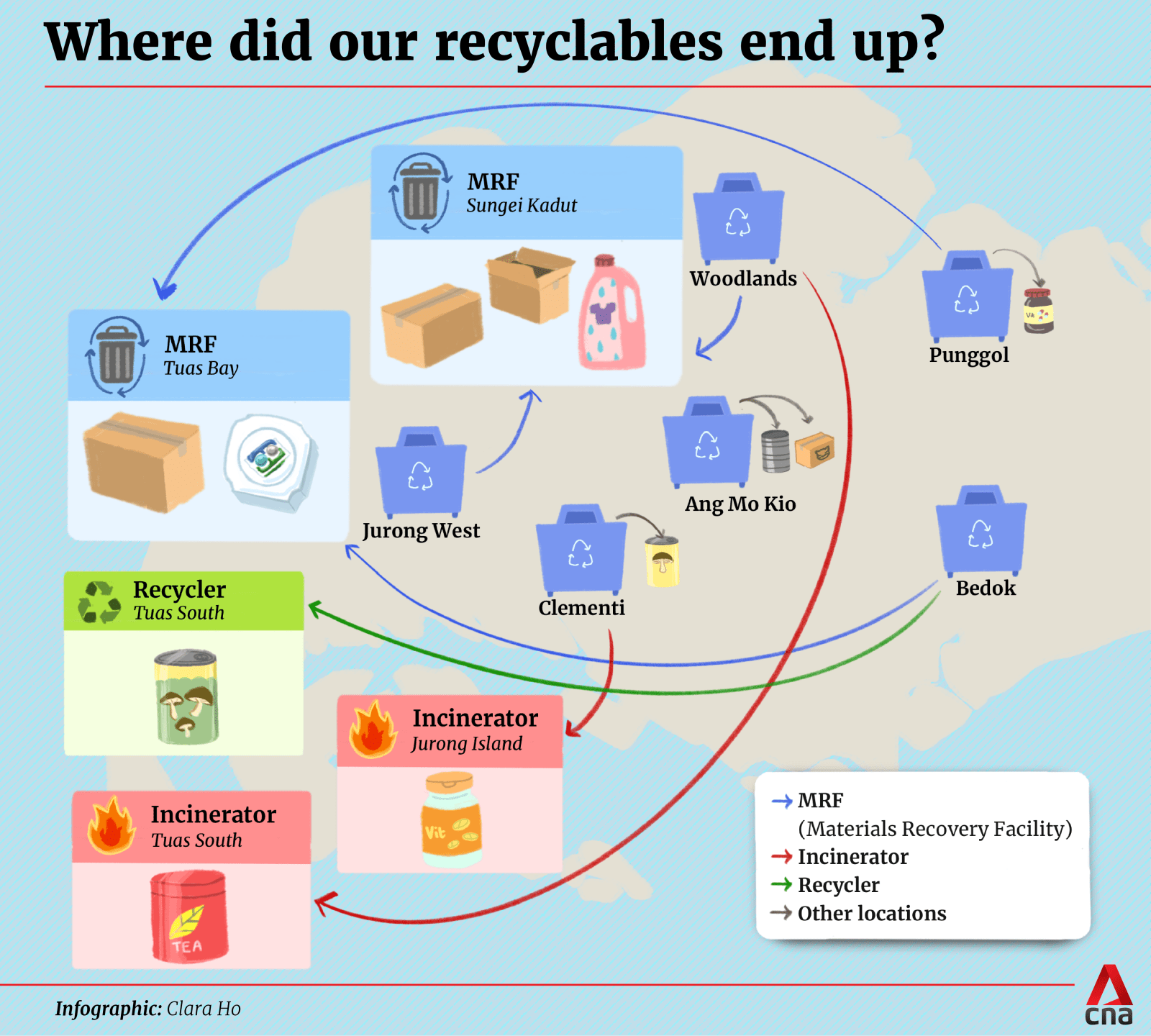

At the end of the experiment in mid-January, eight of the 12 items registered significant movement, while four appeared to have remained near their original locations.

CNA revisited the bins where items registered a small movement and saw that the contents had been refreshed. The four items – two metal cans, a piece of cardboard and a plastic bottle – may have been removed by people and their trackers possibly damaged or disposed of.

Of the eight items with significant movement, five were traced to materials recovery facilities, two to incinerators, and one to a metal recycler.

The five items that ended up in materials recovery facilities were three cardboard pieces and two plastic detergent bottles. The trackers did not register what happened to these items afterward.

The only item traced to a metal recycler – Esun International in Tuas – was a metal can that used to contain mushrooms. Esun International is where scrap metal is sorted and packed for resale, said NEA.

The two items that went to incinerators were a square can that use to contain packaged tea leaves and a plastic vitamin bottle, which went to Keppel Seghers Tuas Waste-to-Energy Plant and Sembcorp Energy from Waste plant in Jurong Island.

Except for Jurong Island, CNA visited the locations to verify the facilities by sight. The Jurong Island facility was confirmed by NEA, which said it was the Sembcorp Energy from Waste plant managed by Sembcorp Environment.

Rejected recyclables and waste from Sembcorp’s facility will be sent to the plant for incineration, NEA said.

CNA then approached the three public waste collectors on why the items may have ended up where they did.

ALBA W&H and SembWaste, which saw items in their bins get incinerated, said that contaminated items get sorted for incineration.

800 Super and ALBA W&H echoed statistics that place the household recycling rate at 60 per cent but the latter said that figures were skewed in the pandemic years.

“Due to more food delivery during COVID19, we have seen an increase in contamination in the blue bins in recent years as residents dispose of their food packaging (which contains food waste) in the blue bin,” a spokesperson said.

“Thankfully, more recently, we have seen a reversal of this trend as there has been a decrease in the contamination rate.”

SembWaste pointed out that attaching a tracker – an item of e-waste that does not belong in blue bins – would render a recyclable item unsuitable for recycling.

WHAT RESULTS SAY

CNA took the results of the experiment to experts and green activists for their input and the views were split.

Some noted that the results were inconclusive for items that were only traced to materials recovery facilities, while others said that they were even brought there was a good sign.

Looking deeper, results could shed light on how certain items were treated.

On why the tea can ended at an incinerator, Prof Tong pointed out that it was unlikely to have been contaminated, as metal did not soil easily.

The Professor at NUS’ Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering thought it more likely that sorters at the materials recovery facility did not pick out the tea can as it looked different from the standard food or drink can.

“Maybe it’s non-standard, the materials recovery facilities, they would pick out what they know … when they see something that they don’t know maybe they will leave it rather than picking it out.”

In contrast, a metal mushroom can was more familiar, and so could have been picked out and sent for processing, the Prof said.

Even then, incineration plants would probably have sorted out residual metals through a magnet to avoid having them incinerated. This was done to keep the incineration process efficient, as more energy would have been needed to burn metals.

In fact, a cardboard piece that was placed in the same blue bin as the tea can remained at the materials recovery facility even as the tea can was sent for incineration.

To Prof Tong, this underlined the idea that contamination had not been the issue, especially since cardboard was more prone to contamination.

The cardboard was likely in good condition, and given that it was easily recognised, was picked out more readily for recycling, he said.

A metal can and an Apple Air Tag. (Photo: CNA/Try Sutrisno Foo)

His colleague, NUS Professor Rajasekhar Balasubramaniam, also pointed out that cardboard generally appeared the same, unlike metals which could come in different types, shapes and sizes.

“It’s much easier to deal with cardboard when it comes to recycling. It doesn’t involve sophisticated technology. All cardboard items can be recycled,” the Professor from the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering said.

“But metal cans, not everything can be recycled, only certain types of metal cans can be recycled due to the facilities that we currently have.”

As for the plastic vitamin bottle that was sent to the incinerator, Prof Tong felt that it could have been contaminated by hard to remove substances like oil.

It could also have been ruined beyond a recognisable shape through its journey, and so was not picked out.

Prof Balasubramaniam was “surprised” that two items went to incinerators.

Putting himself in the shoes of a consumer, he said: “I throw clean recyclable items into designated blue bins, with the expectation that the recyclable items will go to recycling facilities.

“So if the items do not go to recycling facilities, it’s beyond my control, I’m not responsible. So if by any chance those items end up being handled in incinerators I need to know why as a consumer committed to recycling.”

COMMINGLED BINS STILL THE WAY FORWARD?

Views on maintaining the status quo with commingled bins were split.

Convenience is the main rationale behind commingled recycle bins, and is the official reason why Singapore uses it in its National Recycling Programme.

“The commingled system is convenient for residents and facilitates recycling efforts as residents do not need to set aside additional space in their homes to store the different types of recyclables in separate receptacles,” NEA said of blue bins.

This lowered the barrier to recycling, said the agency.

Chairperson of the Government Parliamentary Committee for Sustainability and the Environment and MP for Nee Soon GRC Louis Ng held a similar opinion.

“I think … (we need) to tackle this not from an ignorance standpoint but from a convenience standpoint,” Mr Ng told CNA, adding there was already “significant awareness” on what can be recycled.

A simple way to reduce contamination, Mr Ng suggested, was to make things even more convenient – place a waste bin beside the recycling bin so that people throw their waste in the right bin.

Moving forward, new HDB blocks that have integrated recycling chutes beside waste chutes may reduce the problem of contamination, noted Mr Ng.

National University of Singapore’s Professor Tong Yen Wah speaking to CNA on Feb 7, 2024. (Photo: CNA/Try Sutrisno Foo)

STILL BETTER TO SEPARATE?

Others maintained that segregating waste at the point of collection could reduce contamination, pointing to countries that do the same.

Singapore Institute of Technology’s Senior Manager of Sustainability (Estates) Pek Hai Lin said separating the items would make them look neater, which would in turn encourage recycling.

“When a commingled bin allows for various different materials to be thrown into the same location, it might result in confusion and lowered trust or expectations that items within will be recycled, as it looks very messy,” said Ms Pek.

“This will increase the chances of people treating the blue bin like a regular bin, especially if it looks very messy and dirty, creating a vicious cycle of high contamination rates.”

Sorting the materials early would also save manpower, time, and resources.

She pointed out that initiatives by organisations such as Tzu-Chi Foundation have shown results. Contamination can be minimised if recyclables are sorted more intentionally, she argued.

“Perhaps the next step would be to look at how to mainstream this, like the blue bins,” she added.

Those who are for segregation often point to Japan and South Korea as examples of successful recycling narratives. Both have strict policies for sorting waste, with penalties for non-compliance.

That said, there are many factors contributing to a successful recycling culture, and Singapore might not be there just yet, Ms Pek noted.

The habit is cultivated from young in South Korea and Japan, she said, something Singapore could take heed from.

“Building segregated recycling habits with children from a young age, especially in schools, is more crucial to establishing proper education and action to further reduce the contamination rates in recycling bins in the long term,” she explained.

Recycling rates in countries that sort waste

Countries where sorting waste is mandatory often have higher recycling rates than Singapore.

South Korea has one of the highest recycling and composting rates – at 60 per cent – in the world, according to a 2022 New York Times article citing the World Bank.

Residents there are required to separate food, garbage, recyclables and bulky items into color-coded bags with fines for those who do not comply.

While residents in Japan are also required to sort recyclables, the recycling rate has remained at around 20 per cent throughout the past decade, according to data published by data platform Statista in 2023.

The Netherlands, which also sorts waste into categories that can be easily recycled, has a recycling rate of 56.8 per cent as of 2020, according to the European Environment Agency

Collapse

Expand

There was something else these countries had in common: Legislation.

Prof Tong said examples around the world have showed that when recycling was voluntary, consumers cared less where items went after placing them in recycling bins.

Making recycling a rule would not only ensure consumers practise it, but would help those in the business become more financially feasible.

“If you force everyone to recycle, then you have a lot more of it. Then if you have a lot more of it, then you can do multiple collections. Right now the collection companies, they don’t want to have separate trucks coming because they say it’s not worth it.”

The collection schedule results in blue bins overflowing in some estates.

Prof Balasubramaniam suggested that public waste collectors and material waste recovery facilities explore innovative solutions.

For example, if Singapore were to keep commingled bins, introducing smart blue bins that are capable of automatically sorting waste would make the process more efficient.

The government could also consider decentralising Singapore’s three materials recovery facilities and have them within communities instead, he said.

Not only do you cut down on carbon emissions from transportation, consumers would be closer to the process and hence more aware of how they contribute, compared to having the process “out of sight, out of mind”.

RECYCLE MORE BY RECYCLING LESS

Prof Balasubramaniam counter-argued that having so many different-coloured bins would litter an already-dense housing estate.

Even with the commingled system, there are a handful of separate bins for different materials. E-waste recycle bins take used electronics at some areas, reverse vending machines for drink containers, and textile recycling bins for used clothing, bags, and accessories. Even these have been subject to mess and unwanted items.

But imagine if there were to be even more bins, each catering to a material.

“Segregation reduces the risk of contamination but is not the long term solution as we cannot create an unlimited number of separate bins for each material,” Green Nudge’s Mr Heng said.

Unlike Ms Pek, he thinks that more bins would require more resources and manpower which could raise costs for consumers in the long run.

Mr Heng instead proposed segregating recyclables in a more controlled manner.

“If I would be really, really honest I would say then we should not recycle everything … do a restart and just say we just want to recycle this material or this material.”

For example, just recycle paper, or narrow down to a single kind of plastic item, such as plastic bottles.

The current system suggests that anything made of plastic can or could be recycled, which could be misleading, said Mr Heng.

“Focusing on these items minimises the ambiguity of what can be recycled and helps to shape both producer and consumer expectations of recycling,” he said.

He pointed out that the efficiency of the current process results in consumers forming the “fallacy” that items would be dealt with as long as they are thrown in the bin.

“I feel that what should be done is to slow down the process to allow people to appreciate what can or cannot be thrown out.

“Right now whatever I throw, even if I don’t know whether it’s correct or wrong, it will still be taken away. And there isn’t any feedback mechanism.”

In other words, “in order to recycle more, we may have to recycle less,” he summed up.

In the meantime, for those with the right attitude but with concerns about the current system situation, knowing that items ended up being recycled – in spite of them being mixed with unsuitable or contaminated trash – would likely go some long way in helping to raise Singapore’s recycling rate.

Mrs Wong is firmly in that camp: “I would feel better if I know that the time I take to pick out the recyclables are not wasted.”

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : ChannelNewsAsia – https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/focus-where-do-recyclables-end-you-place-blue-bins-4171776