Rong Deng, researcher at UNSW and one of the report authors, tells PV Tech Premium that these five locations were chosen mainly due to historical PV installations and predictions that the waste stock will be high enough in these areas, but also because they are located near other recycling infrastructure as well.

Asked whether Australia has the capacity to handle current PV waste streams, Deng listed eight private companies that have already been active in the solar recycling space across New South Wales (NSW), Queensland (QLD), Victoria (VIC) and SA (South Australia):

PV Industries (NSW, VIC)

Solar Professional (NSW)

Elecsome (VIC)

Solar Recovery Corporation ((VIC, QLD)

Scipher Technologies (VIC)

Lotus Energy Recycling (VIC)

WA Recycling (WA)

Reclaim PV (SA)

Reclaim PV has gone bankrupt, but there are a few new market entrants not on this list.

Deng notes that Australian firms do not have access to Silicon Valley capital unlike California-headquartered company Solarcycle, which has made trailblazing progress in recycling technology with the recent ability to make brand new solar glass with 50% recycled content. However, some Australian firms are very well established having been active for even longer than PV Cycle, the longstanding collective take-back and recycling scheme for PV panels in Europe.

With no current legislation in Australia for when panels reach end-of-life, it remains a free market. However, a ‘Product Stewardship Scheme’, for which draft proposals have been published, is due to come in next year, which will make either the manufacturer or the large-scale asset owner financially liable for the end-of-life. The draft proposal includes legacy waste, which means that panels installed before the scheme will also be covered under the same rules.

The current missing link in Australia’s PV recycling is its lack of a specialist in solar panel material recovery. Existing recycling companies can delaminate modules, but the commodities are then sent to material recovery facilities that lack specialisation in PV laminates, thus potentially compromising value and output yield.

Australia is a huge reuse market

Explaining why panels are coming offline quicker than expected in Australia, the report notes that at the end of year 10, it is estimated that cumulatively 23% of modules installed in small-scale systems would be decommissioned, due to panel breakage, upgrading to more efficient systems and other motivations of the homeowners, while just 12% of modules in large-scale projects would be decommissioned by year 10.

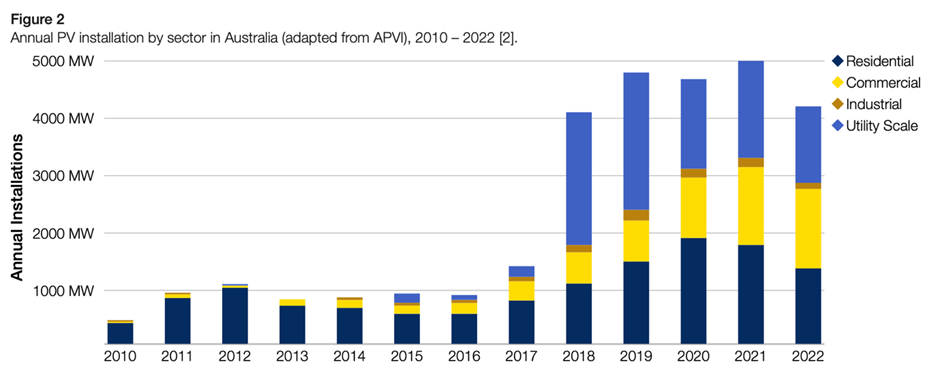

Moreover, Deng says that Australia’s market is mainly dominated by distributed rooftop systems, which were deployed very early in the global PV timeline, with many systems already 10-20 years old.

Historical installations of rooftop PV are far greater than large-scale in Australia (adapted from APVI). Credit: ACAP/UNSW

Historical installations of rooftop PV are far greater than large-scale in Australia (adapted from APVI). Credit: ACAP/UNSW

Having only kicked off in Australia in 2017, large-scale PV systems are not expected to see much repowering for some time. However, Deng says that some repowering occurs in response to extreme weather events, where the whole array is replaced.

In contrast, there are major drivers for homeowners to replace their old rooftop PV systems even if they are functioning well such as the rebate system only lasting 14 years and there being options to take on larger, more efficient, more reliable and longer-lasting modules for a low price at present.

“That’s why in 10 years, we see a very high percentage of decommissioning,” says Deng. “That’s also why we think Australia is a huge reuse market because many panels coming off are technically working.”

Warehouse, dumped or Africa

Without recycling infrastructure in place, end-of-life modules are currently either landfilled, stockpiled in anticipation of a future reuse solution, or exported to Africa, says Deng.

Recyclers charge around AU$10-20 (US$6.62-13.24) per panel plus AU$100-300 for collection depending on distances. Stockpiling requires a warehouse fee of just AU$0.50 per panel, while landfilling costs about AU$2 per panel.

Deng also notes that there is a group of private individuals collecting used panels by offering around AU$20-50 per module then facilitating the export of these panels to Africa for reuse.

“There is no evidence on the news that reports there’s a large proportion of decommissioned panels going to Africa, but that’s actually what’s happening,” Deng adds.

Urgent action needed

By 2030, the majority of waste solar panels are expected to concentrate in the major Australian cities of Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth, and Adelaide, with very little in remote areas. More than 80% of the decommissioned solar panels will come from small-scale distributed PV systems. However, from 2030 onwards, PV waste volumes are anticipated to grow faster in regional and remote areas as large-scale PV systems start to reach the middle or end of their lifecycle, according to the report.

It is recommended that the PV recycling industry in Australia begin with the major cities and then expand to regional Australia to reflect these trends.

A key section of the report also claims that initially, “the volume of end-of-life solar panels is expected to grow rapidly in New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland, which calls for immediate action by the industry to prevent landfilling”.

The cumulative volume of end-of-life solar panels is projected to reach:

280,000 tonnes by 2025

680,000 tonnes by 2030

1 million tonnes between 2034 and 2035

The cumulative volume of end-of-life solar panels in Australia is expected to reach 1 million tonnes by 2035, and the total material value from end-of-life solar panels is projected to surpass AU$1 billion.

Australian closed-loop PV recycling prospects

China has companies covering the entire PV supply chain in-country, with individual manufacturers working across all necessary inputs such as aluminium, glass, and ingots, for example, so its demand for recycled solar module material is much higher than in all other countries.

Australia, like most other countries, does not have a PV manufacturing and supply chain, which means that even though recycled materials such as glass, aluminium, silicon and silver can technically go back into PV manufacturing, there is no local capacity for such a use, says Deng. There is neither an end market nor a high demand for materials so the price for recovered material is low and that further drives down revenues from recycling.

“That’s the biggest challenge, but it’s difficult to overcome because that means we need to bring a lot of infrastructure for manufacturing to bring in the full value chain, which is huge,” Deng adds.

Last month, however, the Australian government made a major play in this arena by launching its Solar Sunshot programme, a AU$1 billion (US$650 million) investment to support the onshore building of ingots, wafers, cells, modules and “related components”, such as inverters and solar glass.

The Sunshot programme mirrors similar moves by other countries looking to have resilient solar supply chains such as the Inflation reduction Act (IRA) in the US, which has driven a boom in US PV manufacturing and allowed the likes of Solarcycle to work seriously on its recycled solar glass products.

Deng says that recycling should be one of the key components of the Sunshot Programme noting that it is a part of the supply chain that should not be overlooked just because it happens to be at the very end of the chain. She believes the programme will initiate some domestic recycling activity and players may start considering incorporating recycled content in their manufacturing processes, with the material feedstock available locally.

Asked if a closed-loop recycling environment is possible, Deng says it depends on the market price. At present, solar panel glass is reused to replace sand in concrete and, driven by very high sustainability criteria for construction in Australia, the construction industry pays a high price of around AU$100 per tonne for solar panel glass to lower its carbon footprint.

Traditional glass bottle recyclers have a huge amount of waste glass feedstock so there is no way to make money from used solar glass down this route.

Deng believes that if a solar glass manufacturer came online in Australia, it would pay a price even higher than the construction industry due to the special optical qualities of solar glass needed for PV modules

“If they are willing to pay more than A$100 per tonne, yes, the circular loop will exist,” she adds.

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : PV Tech – https://www.pv-tech.org/australias-pv-recycling-capabilities-need-to-develop/