Miniature toy soccer players pose in a cluster in the living room, limbs frozen midstride. Like her son’s figurines, Gabriela feels stuck, too.

The Venezuelan asylum-seeker and her teenage son have made it this far, to a one-bedroom apartment in Denver. But the journey to bring him here, to seek critical medical care, meant leaving two other children behind.

As a lesbian, Gabriela is also fleeing harassment; she says her brother was killed for trying to defend her. Yet a sense of security still eludes her here. Without family or many friends in Denver, and no permission to work legally, she’s behind two months of rent.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused on

Record crossings at the southern border are increasingly affecting northern cities. In Denver, the needs of new migrants test the ability of public and private sectors to respond.

Gabriela, who arrived in July, says she expected life in the United States to be tough. “But I didn’t know the magnitude of how difficult it was going to be,” she says in Spanish.

As record-high migration along the U.S.-Mexico border continues to make news, so do cities receiving migrants to the north, like Denver, overwhelmed by a crisis of logistics over the past year. Migrants, too, are often overwhelmed. After the ordeal of crossing America’s southern border, declared by the United Nations as the deadliest land migration route in the world, their precarious journeys endure on the other side.

Whether U.S. border authorities should be releasing migrants who entered unlawfully, ahead of far-off court dates, is under fierce debate. Once migrants arrive, however, their basic needs are testing the benevolence and bandwidth of local governments, nonprofits, and strangers. Amid the challenges, stakeholders are taking steps toward trying to stabilize the situation, raising the question of what sustainable support could look like in an era of record displacement globally.

“We have to be realistic about the fact that people are going to keep migrating,” possibly at high levels, says Elizabeth Jordan, director of the Immigration Law & Policy Clinic at the University of Denver Sturm College of Law.

“The solution is not going to be just closing the border and pretending like people aren’t there,” she adds. “They’re going to be desperate enough to keep coming.”

Sarah Matusek/The Christian Science Monitor

Miniature soccer players pose in the living room of Gabriela, a Venezuelan asylum-seeker, who came to the United States this year in search of protection and medical help for her son. “I’m not a woman who gives up easily,” she says at her apartment in Denver, Oct. 14, 2023.

Despite her hardship, Gabriela, who like others interviewed preferred not to publish her full name for privacy reasons, has been given a hand. After a brief stay with a friend who recommended Denver to her, Gabriela and her son stayed in a shelter for a few weeks. She also found a local group, SOS Venezuela-Denver, whose donation helped pay for her apartment’s water and electricity – utilities that weren’t always reliable back home. Gabriela says she’s also hopeful about the medical attention her son has received.

As the asylum-seeker says, “I’m not a woman who gives up easily.”

Public response

Unlike New York City, which has received five times as many migrants since 2022, Denver has no right-to-shelter policy obligating the municipality to provide a bed for every migrant in need. The city keeps the locations of its migrant shelters undisclosed and hasn’t seen major protests.

Earlier this month, a girl with two French braids wriggles in her chair in a conference room-turned-migrant reception center. At the city-run site in Denver, adults sit quietly, heads bent over phones, waiting for next steps. Here they’re offered temporary shelter or transportation to the destination of their choice.

Helmed by a Democratic mayor and home to some 700,000 residents, the city and county of Denver has served around 26,000 migrants since December, when tracking began. The city’s appeal this fall to the state for use of the National Guard was declined, reportedly due to the absence of an emergency declaration, though the state sent other personnel and has provided funding.

Still, adequate staffing, shelter space, and funding remain concerns, says Jon Ewing, spokesperson for Denver Human Services. Earlier this month, the city set new rules on the amount of time migrants can stay in temporary shelters. Meanwhile, the city is reviewing proposals from potential vendors to contract out its migrant response, reports Axios. The Federal Emergency Management Agency reports awarding the city around $10 million since May.

The Mile High City, meanwhile, reports spending more than $29 million since late 2022 on its migrant response. But by the end of this year, the city government could spend up to $39 million, according to an estimate by the Common Sense Institute, a Colorado think tank that supports free enterprise. These ongoing costs could eventually imperil other financial priorities or increase the cost of city governance, says its recent report.

Looking for work – and workers

Complicating the scope of needs is the fact that many arriving migrants aren’t eligible for work permits.

Those who submit asylum applications wait months before obtaining authorization to work. Though President Joe Biden has offered a temporary legal status to certain Venezuelans already here, which opens the door to lawful work, individuals such as Gabriela still must navigate the process to apply.

Colorado, meanwhile, reports two job openings per every unemployed person in August, though it’s unclear how those open jobs match arriving migrants’ skills. The new arrivals “have skills and talents that Colorado needs,” says a spokesperson for the Colorado Office of New Americans in a statement. “However, without employment authorization, they are unable to enter the formal labor market and fill Colorado’s great need for workforce.”

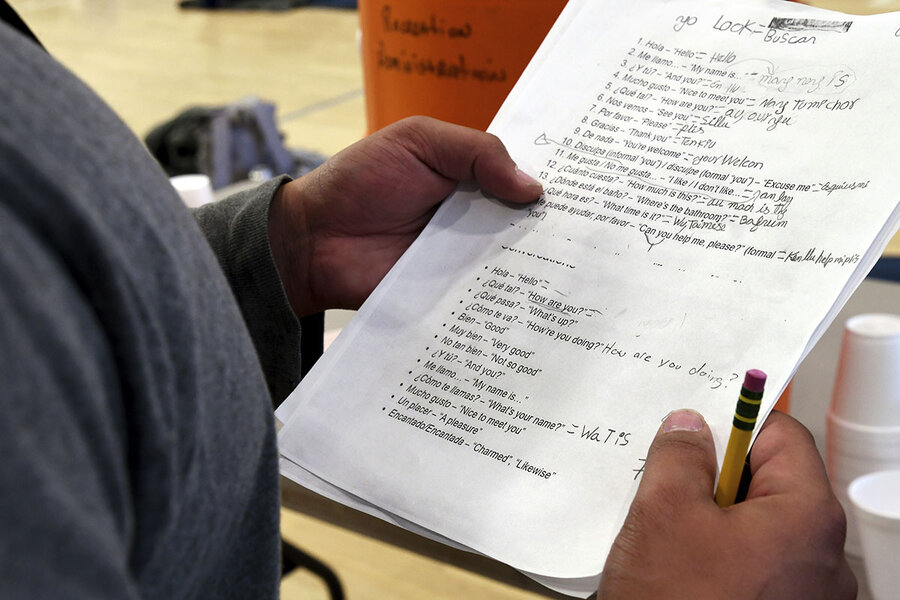

A migrant studies English at a makeshift shelter in Denver, Jan. 6, 2023.

As long as migrants aren’t authorized to work, Denver will need more federal aid to support them, said Mayor Mike Johnston, three months into his first term.

“We think if you bring someone into the country and tell them they can’t work, there’s no choice but to either encourage them to break the law, or to make them survive on public subsidy,” the Democrat told CNN. “We think neither of those are good options.”

Separately, the mayor who campaigned on homelessness aims to “house” 1,000 unsheltered individuals by the end of the year. But now some migrants are also ending up on the street.

Some nearby counties have been cautious about – or opposed to – following Denver’s lead, citing capacity, public health, and safety concerns. That includes neighboring Douglas County, which passed a resolution this month stating it was not a “sanctuary jurisdiction” for migrants. One Latino county commissioner, a Republican, frames it as a “message of compassion.”

“We’re aware of the humanitarian crisis,” says Abe Laydon, who chairs the board of commissioners in Douglas County. Still, he adds, “it’s not humane to welcome individuals into a community without a plan,” especially with winter ahead.

Overburdened systems

Asylum-seekers themselves, like Abdoul from Senegal, understand their vulnerability.

“Some days we don’t even have something to eat, because we don’t have money,” says Abdoul, one of an unknown number of West Africans who’ve arrived in the Denver metro area this year. He doesn’t want to steal, he says in the Wolof language through an interpreter, but just “be able to work and provide for myself.”

Denver’s scramble to accommodate these newcomers belies a reality long known to border towns: Federal failure to reform U.S.-Mexico border policy is felt farther north.

U.S. immigration enforcement depends on the capacity of several federal agencies – including those detaining, deporting, and processing individuals in backlogged immigration courts, says Ariel Ruiz Soto, senior policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute in Washington. Those systems are strained.

The Biden administration’s attempts to manage migrant arrivals, he says, “will always be contingent on the capacity to implement those policies.” That oftentimes requires congressional funding and support, he adds, which is not always there.

Republican governors, meanwhile, have exerted their own political will. Texas Gov. Greg Abbott has publicized the state’s charter of migrant buses to multiple Democratic-led cities, including Denver. Still, some migrants plan to pay their own way, and some arrive by plane.

Joy McCalister (left) and Stevi Soles serve soup to a migrant at a makeshift shelter in Denver, Jan. 6, 2023.

“They’ve helped me a lot”

No matter how migrants arrive, local nonprofits have played a key role in their reception.

At a food bank just west of Denver, a migrant from Venezuela adds groceries to her cart as the child on her hip grips a banana. A friend’s son nearby makes monkey sounds while playing peekaboo.

“They’ve helped me a lot, since we don’t have stable work,” the Venezuelan says of the nonprofit. “My husband works, but he doesn’t work every day.” Life here is a far cry from the country they left, under political and economic crisis.

Here at the Action Center in Lakewood, adaptation has been key since COVID-19. Pre-pandemic, the nonprofit averaged around 70 to 90 household visits per service day. That swelled to around 200 to 300 during the pandemic, and recently to more than 300 a day – coinciding with more migrants arriving in the state.

To meet the growing need, the center, which offers services beyond food, is seeking more Spanish-speaking volunteers and recently hired two more bilingual staff members.

“We don’t do everything that people need, because no one agency can do everything that people need,” says Laurie Walowitz, director of programs. “But we like to be that connector … to other places that are designed to serve very specific needs.”

Other migrants have found momentum with Centro de los Trabajadores Colorado, also known as Centro Humanitario, which supports workers.

In a red-brick building used by the center in downtown Denver, a few dozen people listen to Norys Castillo. The coordinator of the center’s community economic development program explains how to sign up for English classes offered to members in person and online.

“I recommend in person as much as possible,” she tells them in Spanish. The room seems to murmur in agreement.

A couple from Venezuela, Johana and Jean Carlos, sit among the crowd. Through the nonprofit, Johana recently completed a cleaning course, Jean Carlos one in sustainable building. They say they’ve started to receive work in the mountains.

“I want to make a difference,” says Jean Carlos, who had a construction company and wants to start a business here. Also, he adds, “not depend on the government.”

In Aurora, Denver’s neighbor to the east, a Mauritanian named Mamoudou also wants to work with his own two hands. One bears a scar from back home, when he was injured by police, he says.

With a U.S. Air Force baseball cap, Mamoudou explains that he followed a route popularized by Mauritanians through word-of-mouth and social media – first by flying to Turkey, then Latin America, then continuing north to cross the U.S.-Mexico border by foot. He left behind a life of activism fighting for human rights and the end of slavery, whose ugly legacy in Mauritania still endures. Mamoudou says he knows such injustice firsthand, including working for a lighter-skinned man who never paid him.

By this February, he knew he had to leave. That’s when police took his friend, a fellow activist, to jail and beat him to death, Mamoudou says, speaking in Pulaar through an interpreter. When Mamoudou protested, he says he was brutalized by police.

“I just thought to myself … I have to leave here, because I might get killed.”

After he was processed by border officials, Mamoudou came to Colorado to meet a family member, with whom he’s living here.

“I just want to be able to have a better life, and then live in peace,” he says. But navigating even basic tasks is difficult, such as knowing how to call up a lawyer to seek help with his asylum application. For newcomers, he says, “there’s a lot of things that we don’t know how to do.”

And yet, as more individuals like Mamoudou arrive, nonprofit legal aid groups report that they’re already stretched to capacity.

Sarah Matusek/The Christian Science Monitor

Rafael and Yuletsy, a couple from Venezuela, have found fellowship at a Christian church. It feels “like a family,” says Yuletsy, after the Spanish-language service in Lakewood, Colo., Oct. 15, 2023.

“We just don’t have the resources to meet the need. … I think it’s a funding issue,” says Emily Brock, deputy managing attorney of the children’s program at the Rocky Mountain Immigrant Advocacy Network. In immigration court, when dealing with civil cases, immigrants aren’t entitled to a government-appointed attorney.

“We need to be moving towards universal representation for people in immigration proceedings,” says Ms. Brock. Access to due process is important, she adds, as “the implication of their asylum applications are life-or-death situations.”

Day labor assistance

In Aurora, the Dayton Street Day Labor Center has also been overwhelmed, says Mateos Alvarez, the executive director. Before last fall, the nonprofit had primarily served Central Americans and Mexicans.

Without tracking by jurisdictions beyond Denver to confirm, Mr. Alvarez estimates that hundreds of new migrants have shown up looking for work near his muraled building over the past year in Aurora, many from Mauritania like Mamoudou. It took a few weeks to figure out where they were from, much less what they spoke.

As new arrivals without work authorization land on Aurora streets, Mr. Alvarez has observed they’re displacing other day laborers who’ve relied on that work for years. He’s also concerned that more idling outside for extended periods of time will become a public health issue, as people move “from a place of hopefulness to one of despair.”

Still, the advocate does what he can, such as offering a safe space and food to new migrants like Abdoul Aziz, a welder also from Mauritania.

Grateful for the outreach, the asylum-seeker says, “If I get married and I have a kid, I will name him Mateos,” after Mr. Alvarez.

Helping hands

Other individuals are lending a hand, sometimes through houses of worship.

Haydee Rodríguez recalls her own challenge of integration in the late 1990s as a new immigrant from Mexico. Moved to help, she’s driven migrants who’ve arrived at bus stops to a shelter, bought them underwear and socks, and organized additional donations through her Christian church in Lakewood. Members offer rides to migrants who want to worship there.

“They need clothes. They need shelter. They need empathy, more than anything,” she says at the Spanish-language Sunday service.

Yuletsy and Rafael, a couple from Venezuela, count their blessings. Ms. Rodríguez helped them find an apartment to rent.

Though they left loved ones back home, the Colorado church is “like a family,” says Yuletsy, at a post-service lunch where tacos are piled onto plates. Her partner agrees.

“Even if it’s just an hour or two, it feels good,” says Rafael. Here for less than a year, the pair have begun to pay it forward. They drop off food and clothes to a shelter where fellow migrants stay.

Their gestures reflect a view held by Mr. Ewing, the Denver spokesperson, on the promise and limits of generosity in the area.

“It’s full of good people,” he says. Still, “we can’t do this alone.”

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : The Christian Science Monitor – https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/2023/1030/Amid-migrant-increase-newcomers-and-Coloradans-adapt?icid=rss