Special counsel Jack Smith’s indictment of former President Donald Trump on charges that he attempted to subvert the 2020 election is a sweeping document that touches on the bedrock functions of American democracy. The indictment alleges the former president engaged in conspiracies to defraud the United States of lawful government, to corruptly obstruct the Jan. 6, 2021, Electoral College count in Congress, and to conspire against the people’s right to vote.

But one of the main themes twining through the document’s 45 pages is honesty – or rather, its alleged lack. Mr. Trump, the indictment states, spread lies that the election had been flipped by fraud and that he was the true victor, despite being told by aides and officials that his claims were untrue.

Why We Wrote This

In the most serious indictment yet against former President Donald Trump, jurors will have to decide whether he believed the election was stolen, or whether he intentionally lied about it.

Mr. Trump’s defense against these charges will likely rely in part on the insistence that he believed what he was saying, notwithstanding others’ objections, and that his actions were not corrupt. The case could thus hinge on a jury’s conclusions about the state of mind of a man whose career has often involved bombast and, at the least, a fondness for exaggeration.

“A key factor here is going to be the defendant’s knowledge and intent,” says Shane Stansbury, a senior fellow at the Duke University School of Law.

On New Year’s Day 2021, then-President Donald Trump called Vice President Mike Pence and berated him.

For days Mr. Trump had been pressuring Mr. Pence to use his ceremonial role at the upcoming congressional count of Electoral College votes to help overturn the 2020 election. But Mr. Pence was resisting, saying such a move was unconstitutional. Now he would not even support a lawsuit arguing that the vice president could reject or return a state’s votes.

“You’re too honest,” Mr. Trump said, according to the federal Jan. 6 indictment unveiled on Tuesday.

Why We Wrote This

In the most serious indictment yet against former President Donald Trump, jurors will have to decide whether he believed the election was stolen, or whether he intentionally lied about it.

Special counsel Jack Smith’s indictment of Mr. Trump on charges that he attempted to subvert the 2020 election is a sweeping document that touches on the bedrock functions of American democracy. The indictment alleges the former president engaged in three conspiracies with a crew of aides and advisers: one to defraud the United States of lawful government, another to corruptly obstruct the Jan. 6 Electoral College proceedings, and a third to conspire against the people’s right to vote.

But one of its main themes, twining through the document’s 45 pages, is honesty – or rather, its alleged lack. Four sentences in, special counsel Smith charges that for months after the election, Mr. Trump spread lies that the result had been flipped by fraud and that he was the true victor.

“These claims were false, and the defendant knew they were false,” states the indictment.

What follows is page after page in which prosecutors document specific instances in which Mr. Trump was warned by an aide or top official that particular fraud claims were untrue, and had been proved so, yet he persisted in publicly repeating them.

Mr. Trump’s defense against these federal charges will likely rely at least in part on the insistence that he continued to believe these claims, notwithstanding others’ objections, and that his actions were thus not corrupt at heart.

The outcome of crucial parts of the case could thus depend on a jury’s belief about Mr. Trump’s state of mind – a difficult judgment when it comes to a man whose career has often involved bombast, stubbornness, and, at the least, a fondness for exaggeration.

“Jack Smith knows a key factor here is going to be the defendant’s knowledge and intent, so he placed a lot of emphasis on the defendant’s knowledge and intent. There were whole sections devoted to that,” says Shane Stansbury, a distinguished fellow at the Duke University School of Law and a former assistant U.S. attorney in the Southern District of New York.

Special counsel Jack Smith arrives to speak about an indictment of former President Donald Trump, Tuesday, Aug. 1, 2023, at a Department of Justice office in Washington.

Why this case is unprecedented

Whatever the outcome of Tuesday’s indictment, its filing is likely to stand as a momentous event in the history of the American government.

It’s not the first criminal indictment against a former occupant of the Oval Office. Mr. Trump faces charges brought earlier this year in the New York borough of Manhattan related to hush money payments to a porn star. Nor is it the first federal criminal indictment against an ex-president. In June Mr. Trump was charged with mishandling of classified documents and obstruction, stemming from his retention of presidential records at his Mar-a-Lago estate following his exit from office.

But it is the first time an ex-president has been charged with alleged offenses that amount to an attempt to use their incumbency to illegally retain office. Previous presidents had all followed the example of President George Washington and participated in peaceful transfers of power.

“The charges alleged in the new indictment go to the heart of our democracy and are more serious than the indictments previously lodged against Mr. Trump in Manhattan or Florida,” says Chuck Rosenberg, a former U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, in an email.

The new case also presents more challenges than the Manhattan or Florida ones, Mr. Rosenberg adds, in part due to the fact that prosecutors will have to prove Mr. Trump acted intentionally.

Mr. Trump’s initial appearance in the case is scheduled for Thursday afternoon before a magistrate judge in federal District Court in Washington. In a statement, the former president slammed the case as “election interference.”

“Why did they wait two and a half years to bring these fake charges, right in the middle of President Trump’s winning campaign for 2024?” Mr. Trump said.

Inside an alleged weekslong conspiracy

The indictment focuses on two months, the period between the November 2020 election and the Jan. 6 Capitol riot. It describes in narrative fashion how Mr. Trump and six co-conspirators attempted a wide-ranging effort to keep him in office.

Besides putting pressure on Mr. Pence, Mr. Trump called various state officials to try to get them to improperly override their state vote totals, according to the indictment. He hosted a chaotic White House meeting where some attendees suggested seizing voting machines from around the country. He attempted to appoint a new attorney general to enlist the Justice Department in his efforts and then backed down when other Justice officials threatened to resign.

The indictment alleges that some attorneys associated with Mr. Trump helped organize slates of false Electoral College electors from key states, to give an impression of controversy over results where no evidence of election-changing fraud existed.

Mr. Trump insisted at the time, and still insists, that the election was stolen from him by widespread fraud. There is no credible evidence that fraud on that scale occurred in any state.

The Trump team filed numerous election lawsuits prior to Jan. 6 and lost virtually all of them. The indictment alleges that its efforts went far beyond that.

“Yes, if you are losing an election you can look into the legal options on what could or shouldn’t be done. But that’s ‘legal’ options. Jack Smith’s focus is on illegal stuff,” says Michael Gerhardt, a constitutional law professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law.

“Knowingly” – a key word to be weighed in court

Mr. Smith’s indictment also charges that Mr. Trump knew that the public statements he was making about electoral fraud to justify his actions were false. Vice President Pence, Attorney General William Barr and other top Justice officials, the director of national intelligence, officials at the Department of Homeland Security, and senior White House attorneys all told him so.

“In fact, the Defendant was notified repeatedly that his claims were untrue – often by the people on whom he relied for candid advice on important matters, and who were best positioned to know the facts – and he deliberately disregarded the truth,” states the indictment.

Immediately prior to the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, for instance, Mr. Trump made a number of “knowingly false claims,” in the indictment’s phrase, about election fraud.

He insinuated that 10,000 dead voters had voted in Georgia, for instance. Four days prior, Georgia’s secretary of state had told Mr. Trump this charge was false.

He asserted that there had been 205,000 more votes than voters in Pennsylvania. The acting attorney general and deputy attorney general had explained to him this was false.

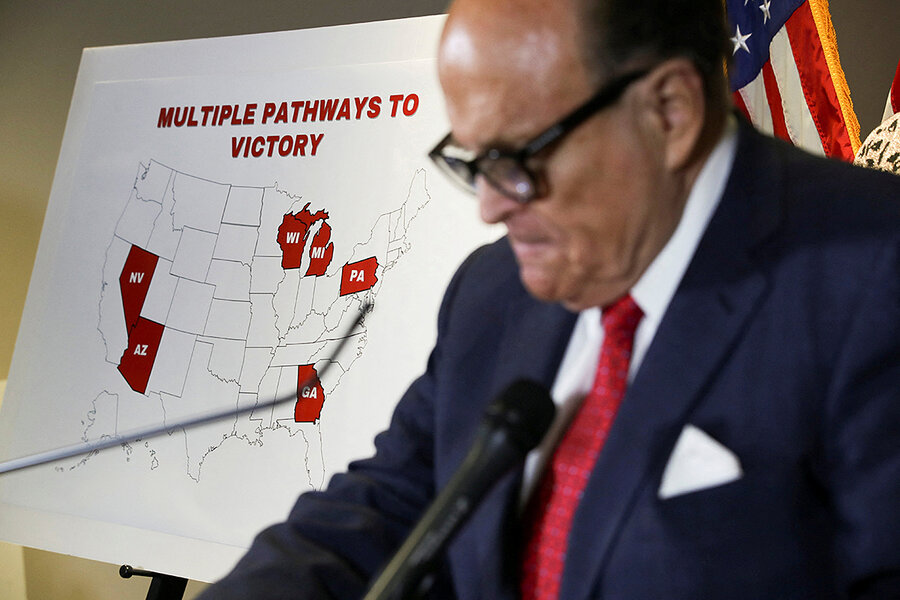

Jonathan Ernst/Reuters/File

Rudy Giuliani, personal attorney to U.S. President Donald Trump, stands in front of a map of election swing states marked as Trump “pathways to victory” during a Nov. 19, 2020, news conference at Republican National Committee headquarters in Washington.

Mr. Trump asserted there had been a suspicious vote dump in Detroit. His attorney general had explained to him this was false, and Mr. Trump’s chief allies in the Michigan Legislature, the House speaker and Senate majority leader, had publicly stated there was no evidence of substantial fraud in the state, according to the indictment.

Furthermore, Mr. Trump appeared to accept he had lost the election prior to Jan. 6, at least to some people. In a Jan. 3 meeting with top national security officials, the then-president agreed with Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley that no action needed to be taken on a particular matter, due to the impending change in administrations.

“Yeah, you’re right, it’s too late for us. We’re going to give that to the next guy,” Mr. Trump calmly agreed, according to the indictment.

However, this is the prosecution’s story of the case, of course. Mr. Trump’s lawyers may be able to frame these instances differently, pointing to others who had insisted to Mr. Trump that the cited instances of fraud really existed – and that the former president, eager to stay in office, grabbed at their views.

As to his agreement with General Milley, Mr. Trump might have had a fleeting moment of doubt, or just wanted to kick a decision down the road, according to National Review writer Jim Geraghty.

“A lot of this case depends upon the jury reaching a clear conclusion about what Trump was thinking and what he believed at particular times,” Mr. Geraghty writes.

Coming next: an expected indictment in Georgia

Thus the Jan. 6 case may be far from a slam-dunk prosecution.

But it is also likely that Mr. Trump has more indictments to come. In Georgia, Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis appears ready to file an election interference case against the former president for his actions pressuring election officials in her state. State charges could come in the next two weeks.

In January 2021, Mr. Trump famously called Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, a fellow Republican, and begged him to “find 11,780 votes, which is one more than we have, because we won this state.”

Tuesday’s federal indictment references this and other actions by Mr. Trump and his allies in the state. That does not preclude a Fulton County indictment, however, says University of Georgia law professor John Meixner, a former assistant U.S. attorney in Michigan.

“There won’t be traditional double-jeopardy concerns about dual charges, because the federal charges will in some ways be of a different nature than exactly what would be charged in Georgia, and the federal and state are also separate sovereigns where each can do what they choose,” says Mr. Meixner.

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : The Christian Science Monitor – https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Politics/2023/0802/At-heart-of-Jan.-6-case-Trump-s-state-of-mind?icid=rss