Your subscription makes our work possible.

We want to bridge divides to reach everyone.

Subscribe

Lynn Williams of the United States (left) takes the ball as Portugal’s Catarina Amado watches during the Women’s World Cup Group E soccer match between Portugal and the U.S. at Eden Park in Auckland, New Zealand, Aug. 1, 2023.

August 2, 2023

The Women’s World Cup 2023 is underway in Australia and New Zealand, and it’s smashing television viewership and ticket sales records.

FIFA, the organizer of the World Cup, says fans have already bought nearly 1.7 million tickets to the games, and corporate sponsorship is surging. More eyes are focused on the biggest event in women’s soccer than ever.

But fans and observers are again asking why the world’s best women players should be awarded so little compared with those on the men’s teams.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused on

The FIFA Women’s World Cup is setting records for viewership and ticket sales. Yet as our charts show, women players lag far behind men in pay, a gap that some nations are trying to address.

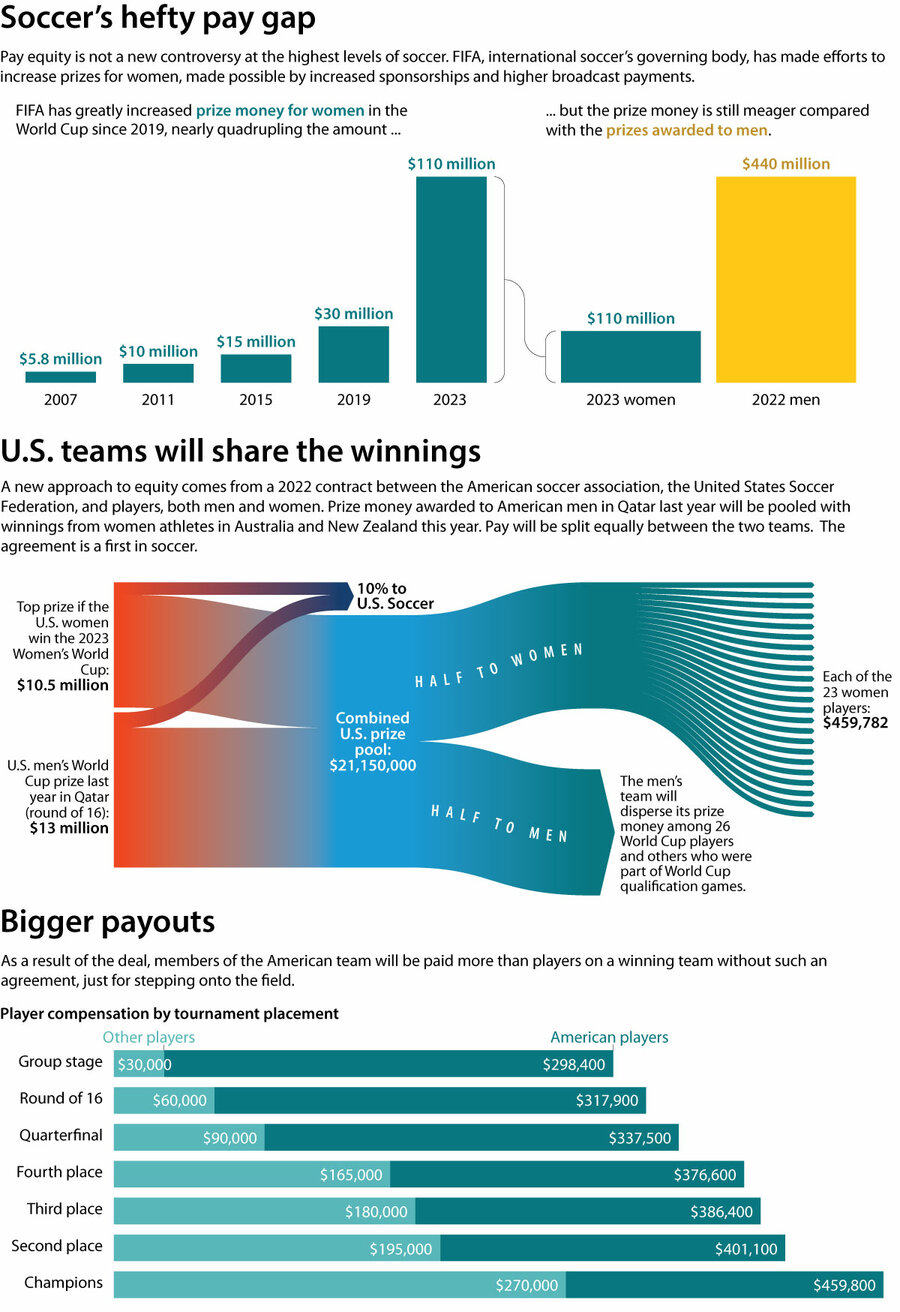

This year’s prize pool totals $110 million, a giant increase from $30 million in 2019 but a far cry from the men’s 2022 World Cup trove of $440 million.

SOURCE:

FIFA, New York Times

|

Jacob Turcotte/Staff

Unhappy with this imbalance, American players from both the men’s team and world champion women’s team reached a deal last year with the United States Soccer Federation, the sport’s national governing body, that makes compensation for athletes fairer. Under the new deal, men and women will pool their winnings and split them 50-50.

FIFA pays prize money to each country’s soccer association, not directly to players. Many countries’ associations pay players per the terms of negotiated labor contracts. But about two-thirds of teams do not have such contracts, leaving their soccer associations to disburse prize money as they see fit. Athletes have complained about late and missed payments, and unfair compensation. The average salary for Women’s World Cup players worldwide in 2022 was $14,000. Earlier this year, FIFA promised to ensure each woman in the tournament was paid at least $30,000 but admitted in June that it could not guarantee national associations would distribute the money in that way.

Some national federations, such as those in Australia and Japan, have made their own collective bargaining agreements intended to improve pay for women athletes, and others, such as Denmark’s, offer player bonuses. But the majority of players in this year’s tournament will not benefit from such agreements and are subject to FIFA’s pay structure.

FIFA says it will aim for pay parity for the 2026 and 2027 men’s and women’s World Cups. Until then, deals like this may be the best way to ensure that prizes for the top tournament are distributed equitably.

You’ve read of free articles.

Subscribe to continue.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Mark Sappenfield

Editor

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn’t possible without your support.

Unlimited digital access $11/month.

Already a subscriber? Login

Digital subscription includes:

Unlimited access to CSMonitor.com.

CSMonitor.com archive.

The Monitor Daily email.

No advertising.

Cancel anytime.

Dear Reader,

About a year ago, I happened upon this statement about the Monitor in the Harvard Business Review – under the charming heading of “do things that don’t interest you”:

“Many things that end up” being meaningful, writes social scientist Joseph Grenny, “have come from conference workshops, articles, or online videos that began as a chore and ended with an insight. My work in Kenya, for example, was heavily influenced by a Christian Science Monitor article I had forced myself to read 10 years earlier. Sometimes, we call things ‘boring’ simply because they lie outside the box we are currently in.”

If you were to come up with a punchline to a joke about the Monitor, that would probably be it. We’re seen as being global, fair, insightful, and perhaps a bit too earnest. We’re the bran muffin of journalism.

But you know what? We change lives. And I’m going to argue that we change lives precisely because we force open that too-small box that most human beings think they live in.

The Monitor is a peculiar little publication that’s hard for the world to figure out. We’re run by a church, but we’re not only for church members and we’re not about converting people. We’re known as being fair even as the world becomes as polarized as at any time since the newspaper’s founding in 1908.

We have a mission beyond circulation, we want to bridge divides. We’re about kicking down the door of thought everywhere and saying, “You are bigger and more capable than you realize. And we can prove it.”

If you’re looking for bran muffin journalism, you can subscribe to the Monitor for $15. You’ll get the Monitor Weekly magazine, the Monitor Daily email, and unlimited access to CSMonitor.com.

Read this article in

https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Society/2023/0802/At-Women-s-World-Cup-a-growing-focus-on-fairness-in-pay

Start your subscription today

https://www.csmonitor.com/subscribe

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : The Christian Science Monitor – https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Society/2023/0802/At-Women-s-World-Cup-a-growing-focus-on-fairness-in-pay?icid=rss