On the 50th anniversary of the Endangered Species Act, I am thinking about extinction and what that means for a creature, a living being, to vanish from existence. Say their names: great auk, passenger pigeon, Carolina parakeet, Steller’s sea cow, Caribbean monk seal, Great Plains wolf, Puerto Rican long-nosed bat, Maryland darter, Utah lake sculpin, Labrador duck, heath hen, Bachman’s warbler, Xerces blue butterfly, Wyoming toad, and Panamanian golden frog—all extinct beginning in the 1800s to present.

Imagine an individual animal or insect or plant—alone—reaching, wandering, wondering, if they are the last of the living members of their kind. Certainly, they must know, sense, or fear this fact. What must it be like to surrender to one’s isolation by way of howl or cry or flight or bloom to attract a response, a glimmer or glint of kin?

Grief is part of extinction that when understood parallels love.

The Sixth Extinction is upon us. It is true, species extinction has been a natural part of the Earth’s evolutionary history, as evidenced with the disappearance of dinosaurs in the Cretaceous Era, 65 million years ago, to the extinctions of the great megafauna such as mammoths and mastodons in the late Pleistocene Era who inhabited the last ice age some 10,000 years ago. But scientists today report an accelerated loss of biodiversity 1,000 times faster than the natural rate of approximately one to five species annually.

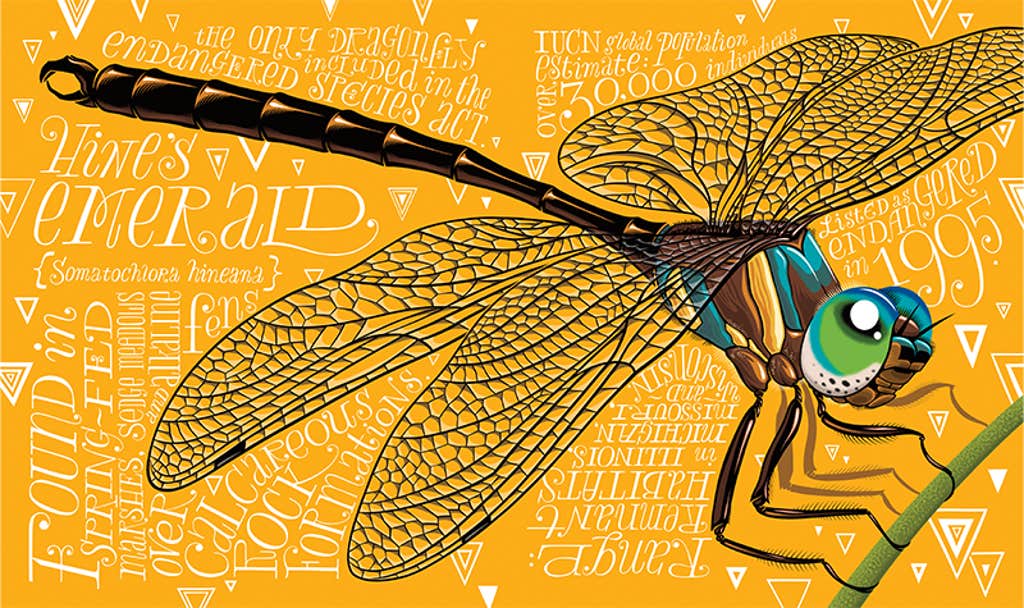

Now on the brink of extinction in North America are the red wolf, wood bison, grizzly bear, black-footed ferret, California condor, ocelot, Florida manatee, northern fur seal, loggerhead turtle, green sea turtle, giant sea bass, Oregon spotted frog, O‘ahu tree snail, rusty-patched bumblebee, Hine’s emerald dragonfly, Kirtland warbler, Eskimo curlew, wood stork, willow flycatcher, North Atlantic right whale, beluga whale, and elkhorn coral.

Loneliness inhabits my body as I whisper the names of the extinct and endangered, something better to do in a circle as ceremony, as we pay our respects and contemplate their lives together. How are we to survive without our companion species on Planet Earth? We are not above them or below them—but side by side—fellow creatures caught in a web of uncertainty in this era of the Anthropocene where our human footprint lands heavy on the Earth.

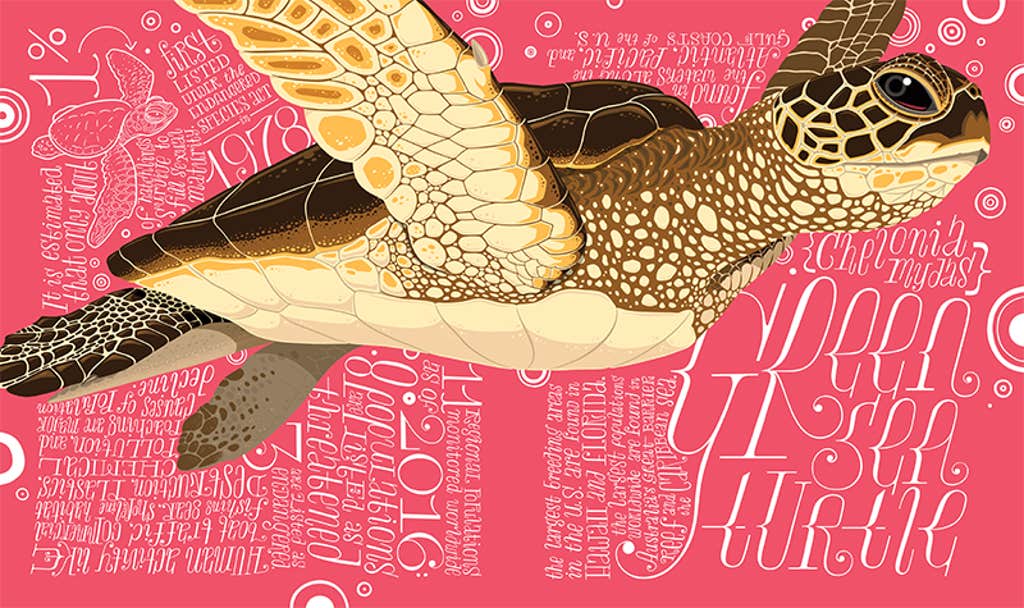

GREEN SEA TURTLE: (Chelonia mydas) Found in the waters along the Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf coasts of the U.S. Human activity like boat traffic, commercial fishing gear, shoreline habitat destruction, plastics, chemical pollution, and poaching are major causes of population decline.

GREEN SEA TURTLE: (Chelonia mydas) Found in the waters along the Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf coasts of the U.S. Human activity like boat traffic, commercial fishing gear, shoreline habitat destruction, plastics, chemical pollution, and poaching are major causes of population decline.

Grief is part of extinction that when understood and witnessed becomes an emotion that parallels love. When the last Rabbs’ fringe-limbed tree frog died in the care of the Atlanta Botanical Gardens on September 26, 2016, I wept. I had visited the Atlanta Botanical Gardens that year and knew the single remaining member of this species, tenderly named “Toughie,” was holding on—his call penetrated the walls of the Gardens—but there was never a call back in response. He was an Endling.

Today, over 1,400 species appear on the Endangered Species list under the jurisdiction of the United States Fish & Wildlife Service, all part of the Endangered Species Act signed into law on December 28, 1973, by President Richard M. Nixon.

President Nixon wrote, “This legislation provides the Federal Government with the needed authority to protect an irreplaceable part of our natural heritage—threatened wildlife.” Just before putting his pen to paper to seal this landmark act, he said, “Nothing is more priceless and more worthy of preservation than the rich array of animal life with which our country has been blessed.”

The Endangered Species Act was introduced in the United States House of Representatives and the Senate by Congressman John Dingle and Senator Mark Hatfield. It passed the House in an overwhelming majority with only four opposing votes. The Senate vote was unanimous. Hard to imagine in this current period of political divisions; harder still to imagine this act of compassion for all living beings remains intact despite previous polarizing times. It is a testament to the moral vision adopted by Congress with a collective commitment to the continuing health of vulnerable species and securing a livable future of all generations—winged, hoofed, scaled, and rooted.

Today, over 1,400 species appear on the Endangered Species list.

Fifty years since its inception, there has been a gradual erosion of the Act. In 1978, when a three-inch perch known as the snail darter was listed as an endangered species, it collided mightily with the Tennessee Valley Authority’s construction of the Tellico Dam. The Endangered Species Act halted the project. This was more than David taking on Goliath. This was a tiny fish swimming in the way of a monstrous water project. The spotted owl in the forests of the Pacific Northwest was threatened by wholesale clearcuts during the 1990s, igniting the timber wars between loggers and environmentalists. Lines were drawn. Violence threatened environmental activists choosing to live in the upper canopies of redwood trees as a protest. Trees were spiked to teach anyone with a chainsaw a lesson: “Hands off old-growth forests.” Any sort of amiable agreement was at loggerheads. Thankfully, solid legal ground was held for both the spotted owl and snail darter, and their endangered status was upheld by science and the courts. In time, solutions were sought through arduous negotiations discussing issues and process. Common ground was eventually found, and in some cases, even consensus.

During the terms of presidents Ronald Reagan and George Herbert Bush, amendments were made to the Endangered Species Act including the formation of a “God Squad” comprised of federal arbiters appointed to balance the common good of capitalism with the survival of a species. It, too, was not without its controversy and contentions. In the American West, where states like Nevada and Utah have a higher percentage of public lands (owned by the federal government) than private lands, a “sagebrush rebellion” ensued, still alive as witnessed by the Bundy standoff at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in 2014. The fight over the rights of private landowners and the rights of the federal government to oversee and protect threatened species continues. The battle between ecology and economy persists, but the Endangered Species Act of 1973 endures.

How do we place a monetary value on what one wild life is worth—let alone the value of a species’ right to continue when weighed against the perfection of adaptive evolution over time? Do we gauge it through dollars per board feet, or the millennial standing of a redwood forest? Do we approve one more golf course in the desert, or act on behalf of a community of threatened Utah prairie dogs in times of drought? How do we balance the health of a declining grizzly bear population against the wealth of private landowners in a state like Montana and with a desire for a second or third home in Paradise Valley? Respect, restraint, and accommodating the rights of other species continue to butt up against the individual dreams and desires of humans.

RED WOLF: (Canis rufus) Once found throughout the Southeastern U.S. Causes of its near-extinction in the wild include shooting, poisoning, roadside fatalities, habitat destruction, and interbreeding with coyotes. The killing of red wolves reintroduced to federal and state lands in North Carolina has thwarted recovery efforts.

RED WOLF: (Canis rufus) Once found throughout the Southeastern U.S. Causes of its near-extinction in the wild include shooting, poisoning, roadside fatalities, habitat destruction, and interbreeding with coyotes. The killing of red wolves reintroduced to federal and state lands in North Carolina has thwarted recovery efforts.

The International Union of Concern for Nature (IUCN) has a “red data book” that is the gold standard for the “global extinction risk status of animal, fungus, and plant species.” It is known as the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, established in 1964 and updated continuously. We know, through shared science from governments around that world, that biodiversity is on the decline. In 2022, the IUCN has registered more than 142,500 species on the Red List, with more than 40,000 species threatened with extinction: 41 percent of amphibians, 37 percent of sharks and rays, 34 percent of conifers, 33 percent of reef building corals, 26 percent of mammals, and 13 percent of birds. The breakdown is sobering.

Why should we care? We care because we have co-evolved with the living world of animals and plants and fungi and corals and multitudes of microorganisms, many that have never been seen or defined or categorized or named. “The great majority of species of organisms—possibly in excess of 90 percent—remain unknown to science,” the venerated scientist E. O. Wilson wrote before his death in 2022. He also coined a word, biophilia, to mean “the inborn affinity human beings have for other forms of life, an affiliation evoked, according to circumstance, by pleasure, or a sense of security, or awe, or even fascination blended by revulsion.” We care because it is in our deepest nature to live and learn and evolve from the life that surrounds us.

We imitate animals through dance and song and stories. In ceremonies, their skins are donned; in fashion, we wear their prints and feathers; in art, we draw them, paint them, and sculpt them, making masks to honor them; and in every religious tradition animals from snakes to lions to locusts and doves we reference them, we fear them, we worship them and bow. They are our teachers, our mentors and guides capable of portending our future because they were here to meet us when we arrived. “Men are born human. What they must learn is to be animal,” says ecologist Paul Shepard. “If they learn otherwise it may kill them, and kill life on the planet.”

If the Endangered Species Act itself has been protected for the past five decades by the passionate research of scientists and the savvy of committed lawyers with the flexed muscle of grassroots organizations, I believe what is being called forth in the 21st century is the strength of our collective will—fierce and direct. As David Lamfrom, Vice President of Regional Programs at the National Parks Conservation Association, says, “Our opening position now must be ‘No more.’” No more compromises on the survival of grizzly bears, wolves, and wolverines. No more “taking” (a euphemism for killing) of prairie dogs and development in the critical habitat of black-footed ferrets and burrowing owls. No more draining of precious wetlands where scores of threatened species are making their last stands. No more apathy on our part. No more wondering what we can do when the Endangered Species Act needs heart-fires of support when Congress will inevitably move again to threaten the Act’s beautiful, shimmering teeth of accountability in the name of justice for all.

“Right now, in the amazing moment that to us counts as the present, we are deciding, without quite meaning to, which evolutionary pathways will remain open and which will forever be closed,” writes Elizabeth Kolbert in The Sixth Extinction. “No other creature has ever managed this and it will, unfortunately, be our most enduring legacy.”

How do we place a monetary value on what one wild life is worth?

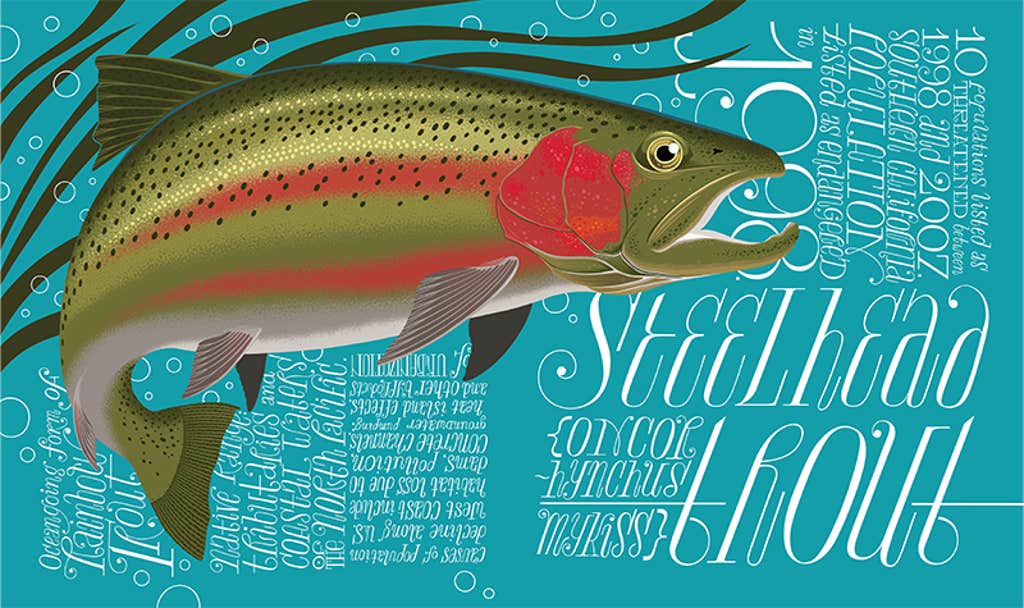

The illustrations here are by Allen Crawford. He has created an illustrated celebration of the Endangered Species Act, vibrant and instructive by featuring 80 vulnerable species. He is a visionary artist who not only cares about the survival and sustaining grace of the “more-than-human world” but has chosen to put his gifts to use with the intention of inspiring us to care more deeply and act more consciously on behalf of these vulnerable creatures.

Some of the creatures are critically endangered. Some are threatened. Perhaps as you come to know their stories, you will be moved to seek out an endangered or threatened species that lives close to you, learn their natural history and give them not only your attention, but your devotion. Or maybe you know of a species in your state or a particular ecosystem that needs federal protection. You can support a specific species campaign addressed to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to nominate newly threatened plants and animals to be concerned for protection under the Endangered Species list. Advocates in the Northern Rockies are working to upgrade the status of the wolverine from a “species of concern” to “threatened.” The Endangered Species Act is an act of love that asks for our engagement, each in our own way with the gifts that are ours in the places we call home. Learn their names. Speak their names. Remember their names. Act.

As a child, I watched the men I loved in my family lift their high-powered rifles and shoot one prairie dog after another and another for fun, and then walk away. They called them “pop-guts.” On the way back to our camp, I stepped over their small blood-soaked, blown-apart bodies left in the matted grasses of their prairie dog town. And then, a single prairie dog raised her head out of a burrow and stood up and faced me. I froze in place, unable to avoid her gaze. She disappeared underground. On that day, I made a vow, short of standing in front of my father’s rifle, that I would be their ally. I have tried to keep that vow.

STEELHEAD TROUT: (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Oceangoing form of rainbow trout found in the tributaries and coastal waters of the North Pacific. Causes of population decline along the U.S. West Coast include habitat loss due to dams, pollution, concrete channels, groundwater pumping, heat island effects, and other byproducts of urbanization.

STEELHEAD TROUT: (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Oceangoing form of rainbow trout found in the tributaries and coastal waters of the North Pacific. Causes of population decline along the U.S. West Coast include habitat loss due to dams, pollution, concrete channels, groundwater pumping, heat island effects, and other byproducts of urbanization.

I graduated from high school in 1973, the same year the Endangered Species Act was signed into law. At that time only 3,300 Utah prairie dogs remained in 37 isolated colonies in the state of Utah. Due to political pressure from ranchers and developers, they were not listed on the original Endangered Species list. Prairie dogs were seen as vermin.

In 1977, I lobbied the Utah legislature as a graduate student in education from the University of Utah. I had created a Utah prairie dog curriculum for the Salt Lake City school district. At the State Capitol, I was met with incredulity and disdain by representatives who insisted on calling prairie dogs “varmints.” The Speaker of the House handed me a recipe for “Prairie Dog Stew.” Finally, in 1984, the Utah prairie dog was added to the Fish & Wildlife’s Endangered Species list and remains on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

In 2000, in a special millennial issue of The New York Times Magazine, the Utah prairie dog was featured as one of 10 species most likely to become extinct by the next millennium. Their fate was to become a ghost species. I wrote a book on prairie dogs. Every month I sent a picture of prairie dogs in different poses (one with a helmet and bazooka) to friends at The Utah Nature Conservancy, a playful nudge for protection. Did any of these gestures make a difference? It made a difference to me. This was my wild promise that became a vow I made to the lone Utah prairie dog who survived my family’s massacre.

What is the difference between a promise and a vow? A promise is “a specific declaration or assurance that one will do a particular thing or that a particular thing will happen.” A vow is “a solemn promise”—a deepening gesture that one makes with one’s whole being. Both are nouns. But what if we see them as verbs, as actions that grow out of a commitment?

A promise becomes giving one’s word—“assuring someone that one will definitely do, give, or arrange something; undertake or declare that something will happen.” A vow is an open-ended commitment over time that moves into the realm of a sacred obligation—“dedicated to someone or something, especially a deity.” If one believes, as I do, that the Divine resides in all living things, then there are many gods among us, in a myriad of shapes and sizes and forms.

Perhaps you have often felt yourself watched. Perhaps you were right.

–Helen Mort, The Illustrated Woman

Whether it is a wolf lodged deep inside our psyches or a mite invisible to our eyes, each species encompasses a life honed to perfection over millions of generations. Our wild promise within the Endangered Species Act, to protect and keep safe threatened and critically endangered species from extinction, can become a vow of action. What I have learned from spending time in Utah prairie dog towns is that community matters. These communal animals watch out for each other. Each member of a colony has a carefully communicated role to play.

Could they be watching out for us, as well? By caring for their own kind, prairie dogs simultaneously create an environment where other species can thrive. They are a keystone species that other species rely on for their survival. Where prairie dogs dwell other species dwell, also—including black widow spiders, pronghorn antelope, burrowing owls, badgers, meadowlarks, and rattlesnakes. Each species fulfills their ecological niche. Diversity equals stability. Prairie dogs continue to teach me, we are nothing without community in all its magnificent and infinite variety.

Do we approve one more golf course in the desert?

We, too, are threatened. Endangered species are showing us now that we are not immune from the perils of climate collapse. The issues affecting endangered species, such as habitat destruction from extreme weather, to drought, to fires, are inextricably linked. My friend Becky Duet and her family, who are Cajun, have lived in the bayous of Louisiana for generations. They lost their home in the summer of 2021 to Hurricane Ida. The eye of the hurricane split in two, something they had never seen. There was no momentary calm—what came instead were 190 miles per hour winds that threatened their lives and blew apart their town of Galliano. Her husband Earl, a renowned shrimper in the area, lost his way a decade ago as the grasslands and waterways he once knew by heart disappeared to erosion. Now the maze of shrimping in the bayous has been lost to open waters. Louisiana loses one football field of soil every hour. The Duet family now belongs to tens of thousands of climate refugees who see what is happening and are sounding the alarm, but not enough of us are listening, watching, and bearing witness to a world transformed.

Our ignorance and arrogance are threatening life on the planet as we continue to live as though nothing has changed, as though our reliance on fossil fuels has no consequences, as if holding fast to our beliefs that we have the right to drill for more and more oil at greater and greater cost to the Earth and its inhabitants will make it right.

HINE’S EMERALD DRAGONFLY: (Somatochlora hineana) The only dragonfly included in the Endangered Species Act. Found in spring-fed marshes, sedge meadows, and alkaline fens over calcareous rock formations in Illinois, Michigan, Missouri, and Wisconsin.

HINE’S EMERALD DRAGONFLY: (Somatochlora hineana) The only dragonfly included in the Endangered Species Act. Found in spring-fed marshes, sedge meadows, and alkaline fens over calcareous rock formations in Illinois, Michigan, Missouri, and Wisconsin.

This is not a homily, this is a fact: Our relentless drive to protect our American lifestyle while we continue devouring the sacred sites of endangered species for our own short-lived additions is our pathology. This will be our undoing. Respect and restraint will be our healing. Our unconscious and conscious acts of killing must be transformed into intentional acts of reverential vigilance. Animals are leaving us. Plants and fungi are offering us their medicines so that we might see more clearly with greater understanding, our place in the wholeness of things. Native bees continue to pollinate wildflowers and grace us with honey even as their populations plummet. On hands and knees, we would do well to take the humble stance of an animal and remember who we are, where we belong, and what our responsibilities to those with whom we share this planet must become and why.

I often return to these lines from the prose poem “Dead Seal near McClure’s Beach” written by Robert Bly—the poem that made me care. His words about a seal dying from spilled oil held a mirror up to my own complicity in the suffering of animals:

. . . goodbye brother, die in the sound of waves, forgive us if we have killed you, long live your race, your inner-tube race, so uncomfortable on land, so comfortable in the ocean. Be comfortable in death then, when the sand will be out of your nostrils, and you can swim in long loops through the pure death, ducking under as assassinations break above you. You don’t want to be touched by me. I climb the cliff and go home the other way.

We can write a different ending to the stories of critically endangered species and all the miraculous creatures large and small whose populations are in decline. Their lives are in our hands. A new ending is possible once we begin to love and live differently. ![]()

Terry Tempest Williams is an American writer, educator, and conservationist. Her award-winning books include Refuge, When Women Were Birds, The Hour of Land, and Erosion: Essays of Undoing. She lives in Castle Valley, Utah.

Allen Crawford is the illustrator of Whitman Illuminated: Song of Myself. He and his wife, Susan, are proprietors of the design/illustration studio Plankton Art Co. Their illustrations are on permanent display at the American Museum of Natural History’s Milstein Hall of Ocean Life. His work has appeared in numerous publications including The New York Times, Orion, and Art in America. He lives in Mt. Holly, New Jersey.

Copyright © 2023 by Allen Crawford. Illustrations reprinted with permission from Tin House. Introductory essay copyright (© 2023 by Terry Tempest Williams. Reprinted with permission from Tin House.

Lead illustration: IVORY BILLED WOODPECKER: (Campephilus principalis) Proposed delisting due to extinction in 2021. Status under review: recent evidence suggests its possible survival.

Get the Nautilus newsletter

Cutting-edge science, unraveled by the very brightest living thinkers.

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : Nautilus – https://nautil.us/i-am-thinking-about-extinction-355377/