Joe Biden exits the Beast – the president’s heavily armored stretch limousine – and makes his way into the Regal Lounge, a Black-owned barbershop in Columbia, South Carolina.

The space is cramped, but President Biden works the room like a pro. Customers and stylists alike stop everything to greet the surprise guest, here to campaign ahead of the state’s Democratic primary. A member of the Secret Service instructs a barber to put down his razor; after all, he’s cheek by jowl with the leader of the free world.

The setting, of course, is calculated. The largely Democratic Black vote is critical to Mr. Biden’s election prospects in November – as it was in 2020 – and Black men, in particular, have been peeling away from the president’s column.

Why We Wrote This

President Biden’s decades of experience have brought valuable perspective, supporters say. Yet the next president will face uniquely modern challenges. Is Mr. Biden’s age a liability or an asset? It may be both.

After a few minutes inside the Regal, we reporters accompanying Mr. Biden are escorted out. But the president stays inside for a full half-hour. This is the Biden way: More than just grinning for the cameras, he needs to shake every hand, pose for selfies, win people over one by one.

President Joe Biden greets a patron during an unannounced visit to the Regal Lounge barbershop in Columbia, South Carolina, Jan. 27, 2024.

“That’s where Biden is most comfortable” – engaging with the public, says former Republican Sen. Chuck Hagel of Nebraska, a friend of the president’s for 25 years. “He loves people.”

In many ways, Mr. Biden’s brand of politics is as old-school as they come. He has been a fixture in Washington since his first election to the Senate in 1972, and his approach can be seen as a relic of a bygone era, when respect and civility in public life were the norm, and the ability to work across the aisle and cut legislative deals was the name of the game.

Today, after 36 years as a senator from Delaware, eight years as vice president, and three-plus years as president, Mr. Biden faces the challenge of a lifetime: fending off likely GOP nominee Donald Trump amid rampant partisan dysfunction, growing isolationism, a crisis on the southern U.S. border, and an increasingly restive left. His job approval rating with the public is now consistently under 40%.

In his State of the Union message Thursday night, Mr. Biden will have his biggest opportunity before the November election to address a national audience – and woo back supporters. But it’s likely to take more than a prime-time speech to turn opinion around.

A man of the center?

Four years ago, Mr. Biden’s reputation as a moderate, experienced Washington hand who could restore a sense of normality after former President Trump’s tumultuous term helped him win the Democratic nomination and then the presidency.

But that image as a man of the center – able to not only bridge the two main parties but also keep his own side united – has been undercut by the realities of governing in this fractious time. Early in his term, he embraced many of the left’s priorities, going big on pandemic relief spending before touting efforts at deficit reduction. And while the economic picture has grown increasingly rosy, the verdict is still out, and a raft of issues from across the political spectrum – from inflation to the border to Israel – could be his undoing.

Joe Biden (right) holds his sons, Beau (left) and Hunter, during the Democratic state convention in 1972. With him are his first wife, Neilia (center), and Gov.-elect Sherman W. Tribbitt and his wife, Jeanne.

Mr. Biden’s ace is that he is tenacious. In his youth, he worked hard to overcome a stutter, a disability he has mostly beaten. He pursued the presidency for decades before reaching the mountaintop. He had to propose to his wife, Jill, five times before she said yes.

He will also do anything, it seems, to protect his family, including his troubled son Hunter, who faces multiple federal indictments on tax and gun charges and a congressional investigation into his business dealings. Republican-led House investigative committees have had the president himself in their sights, but so far have not presented evidence of an impeachable offense.

Now, much like when Mr. Trump asserted at the 2016 GOP convention, “I alone can fix it,” Mr. Biden is displaying a similar mentality. He beat Mr. Trump once and he can do it again, his words and actions suggest – even as the 81-year-old president faces growing questions about his stamina and sharpness.

An ABC News/Ipsos poll, taken right after a February special counsel report depicted Mr. Biden as a “well-meaning, elderly man with a poor memory,” found that a whopping 86% of Americans think Mr. Biden is too old for another term. Some 62% also think Mr. Trump, at 77, is too old. But while the former president also misspeaks regularly, his delivery and physical presence onstage are more robust.

“The visuals are hard” for Mr. Biden, says veteran Democratic strategist Peter Fenn, who has known the president since the 1970s.

Still, Mr. Fenn sees the younger version of the president shining through – a man who believes in his own problem-solving abilities and yearns for the old way of doing things.

Mr. Biden speaks at the South Carolina State Fairgrounds, in Columbia, Jan. 27, 2024.

“What Biden wants is a government that works, and that sense of normalcy and regular order,” Mr. Fenn says. “He just wants to set the table for the future – a return, in the next four years, of decency and respect for truth.”

Ultimately, there’s no denying a central paradox of the 2024 election. Mr. Biden is old enough to remember when Black Americans sat at the back of the bus, when the Cold War raged, when TV was in its infancy. And those years of experience have brought a valuable perspective on both how far America has come and where it needs to go, supporters say.

Yet the next president will face the most modern of challenges, from artificial intelligence to climate change. Is Mr. Biden’s age a liability or an asset? The answer may well be both.

Finishing the job

During the last campaign, Mr. Biden strongly suggested he would be a one-termer if he won.

“Look, I view myself as a bridge, not as anything else,” Mr. Biden said in March 2020, right after effectively clinching the Democratic nomination. “There’s an entire generation of leaders you saw stand behind me. They are the future of this country.”

He was referring to then-California Sen. Kamala Harris, New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, and Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, all viewed as potential running mates at the time. Vice President Harris got the nod, and today has even lower job approval ratings than Mr. Biden. Some analysts suggest that her weak political standing is one reason Mr. Biden felt compelled to run again.

President Joe Biden holds the hand of Vice President Kamala Harris as he speaks at a Black History Month reception in the White House, Feb. 6, 2024.

After special counsel Robert Hur declined to charge Mr. Biden for his handling of classified documents – but raised fresh questions about his memory – a CNN reporter reminded Mr. Biden that in December, he had said there are “probably 50” Democrats who could beat Mr. Trump.

“So why does it have to be you now?” the reporter asked.

Mr. Biden’s response: “Because I’m the most qualified person in this country to be president of the United States.” And, he added, to “finish the job I started.”

Ted Kaufman – a close friend of Mr. Biden’s and a decadeslong Senate aide – says he’s not surprised Mr. Biden is going for a second term.

“It’s not an ego thing,” says former Senator Kaufman, who was appointed to Mr. Biden’s Delaware seat for two years after his boss won the vice presidency. Rather, Mr. Biden’s thought process boiled down to this: “How would he feel if he didn’t run, and Trump got elected president? What would that be like in terms of his golden years, and how he lives out the rest of his life?”

That mindset permeated Mr. Biden’s thinking when he ran against Mr. Trump in 2020, and he feels it just as strongly now, Mr. Kaufman says.

Mr. Biden’s friend also points to a life marked with tragedies that have forged resilience. There was the car crash in 1972 that killed his first wife and baby daughter, leaving him as a single parent with two young sons; two life-threatening medical emergencies; the death of his son Beau, who was a rising political star in his own right; and his son Hunter’s addiction and legal problems.

Hunter Biden (center), accompanied by his attorney Abbe Lowell (at left), talks to reporters as they leave a House Oversight Committee hearing on Capitol Hill, in Washington, Jan. 10, 2024.

“What all that does to someone, in my experience, is it builds character,” Mr. Kaufman says. “I’m not saying all politicians lie and steal; that’s not been my experience. But he’s faced some incredibly difficult things, things that would daunt anyone else.”

Democrats say Mr. Biden has a strong record of accomplishments to tout. Despite enormous economic challenges coming out of the pandemic, a long-predicted recession never materialized, and January marked the 24th straight month with unemployment under 4%, which is considered full employment. Still, the sharp spike in inflation early on left many Americans feeling poorer, and the lingering effects could harm the president’s efforts to win back blue-collar voters.

Mr. Biden also points to student loan forgiveness and price reductions for some prescription drugs under Medicare as big wins. And he notes that infrastructure projects funded under the $1.2 trillion Bipartisan Infrastructure Law are underway, as are investments addressing climate change via the Inflation Reduction Act.

But there’s no denying a top political liability – the crisis on the southern border, where illegal crossings have averaged a record 2 million a year since Mr. Biden took office. Mr. Trump effectively killed bipartisan border legislation recently in the Senate by voicing his objection, leaving the president to address the issue without congressional help. Trump critics say the former president wants continued border chaos on Mr. Biden’s watch, rather than a solution.

Jose Luis Gonzalez/Reuters

Migrants seeking asylum in the United States gather near the border wall, as seen from Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, Jan. 22, 2024.

Mr. Biden’s wish list for a second term is long and ambitious – and focused on bringing down costs for Americans struggling to make ends meet. Highlights include federal money for child care, as pandemic funds dry up; an expansion of the reduction in some prescription drug costs to cover all Americans; and free prekindergarten and community college. To pay for this, Mr. Biden proposes raising taxes on wealthy people.

More broadly, the president’s campaign for a second term is centered on nothing less than the preservation of democracy – or what Mr. Biden calls “a battle for the soul of America.” Four years ago, he ran to defeat Mr. Trump and restore, as he likes to say, a sense of common national purpose. Today, those same goals hold, but with more overt fears expressed by some that a second Trump term could creep toward authoritarianism.

Perhaps Mr. Biden’s greatest unfulfilled promise from his 2021 inaugural was a pledge to restore national unity – beginning with a call to “treat each other with dignity and respect.”

Discontent on the left

Lately, much of the disunity has seemed to come from Mr. Biden’s own party. He is routinely confronted at public events by unruly left-wing activists over the United States’ handling of Israel and the war in Gaza, as well as climate change.

Some pundits have argued Mr. Biden needs a “Sister Souljah” moment – that is, he should publicly rebuke his party’s most strident wing as a way to reposition himself in the political center. In 1992, then-presidential candidate Bill Clinton took on Black rapper and activist Sister Souljah, helping to rebrand the Democratic Party as not a captive of the left. Sister Souljah had made comments on race that were widely deemed offensive.

But some who know Mr. Biden best scoff at the idea of him taking on left-wing protesters in that way.

“Come on, really?” says Mr. Kaufman. “You think Joe Biden’s going to be spooked by some of these demonstrators?”

Typically, when protesters disrupt his events, Mr. Biden waits for security to escort them out and then calmly resumes speaking. At times he expresses empathy.

Mr. Biden visits the John A. Blatnik Memorial Bridge that connects Duluth, Minnesota, to Superior, Wisconsin, March 2, 2022. His administration has announced nearly $5 billion in grants for similar projects.

“They feel deeply,” the president said at a campaign rally in January, after protesters opposed to U.S. support for Israel’s offensive in Gaza interrupted him about a dozen times.

Supporters say that by not engaging with protesters, he’s showing confidence in his position and a willingness to let the debate be fully aired. But Mr. Biden’s patience can have its limits, as another longtime friend suggests.

“There will come a time in the next eight or nine months where something will happen, and he’ll just say, ‘Enough,’” says Mr. Fenn.

With some top administration officials, protesters have become especially brazen. Since January, dozens of people have camped outside Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s home in suburban Virginia, demanding a cease-fire in Gaza.

Heather, a Muslim woman from Chicago who declined to give her last name, says she won’t vote for Mr. Biden. She cites the nearly 30,000 Palestinians in Gaza, many of them women and children, killed by U.S.-backed Israel since the war began.

“Many of the people in my social circle are totally disgusted with Biden,” says Heather, who drove 13 hours to join the Blinken encampment for a bit.

A successful reelection effort by Mr. Biden will depend on his ability to sew together many constituencies and convince them to turn out. For some young progressives, disillusioned over Mr. Biden’s strong support for Israel following Hamas’ attack on the Jewish state Oct. 7, the choice may not be Biden-Trump; it could be whether to vote third-party – or not at all.

Evolving views

Typically, Mr. Biden responds to the age question in two ways: “Watch me,” and then some version of, “With age comes wisdom.”

First lady Jill Biden attends a campaign event focusing on abortion rights in Manassas, Virginia, Jan. 23, 2024.

Indeed, looking back over his long career, there’s no question that Mr. Biden has evolved both politically and personally.

One example: He learned to stop being “handsy” with people – or “getting a little too close,” as a Biden friend put it. Like many male politicians of his generation, he was once known as a hugger and a backslapper, a habit that could make women in particular feel uncomfortable. But in 2019, as Mr. Biden prepared to run for president, aides had a sit-down with him and he changed his ways.

Another trait that Mr. Biden learned to correct was long-windedness. Democratic Sen. Chris Coons of Delaware, a one-time Biden intern who now holds the president’s old Senate seat, recalls stemwinders that could go on for an hour and a half. Today, Senator Coons says, Mr. Biden does less talking and more listening.

“He changed, fundamentally, as vice president and president,” says Mr. Coons, noting that before Mr. Biden became vice president, he hadn’t had a boss for 36 years. “He’s very disciplined – in meetings, in speeches, in engagement. He reads an enormous amount; he’s very present.”

That’s not to say meetings with Mr. Biden don’t often go long. But that’s because he wants everyone to have their say and invites debate, according to aides.

He also seems to have learned from past mistakes. Mr. Biden served as Senate Judiciary Committee chair during the 1991 Supreme Court confirmation hearing for Clarence Thomas, when allegations of sexual harassment by a former subordinate, Anita Hill, cast then-Judge Thomas’ confirmation in doubt and shined a light on the committee’s makeup: all white men.

The case of now-Justice Thomas and now-Professor Hill, both Black, set the politics of race and gender in sharp relief. And when Chairman Biden made a deal with Republicans that prevented four female witnesses from testifying on Ms. Hill’s behalf, that sealed Mr. Thomas’ confirmation. Years later, in 2019, as Mr. Biden prepared to announce his campaign for president, he called Ms. Hill to express regret. She said it wasn’t enough.

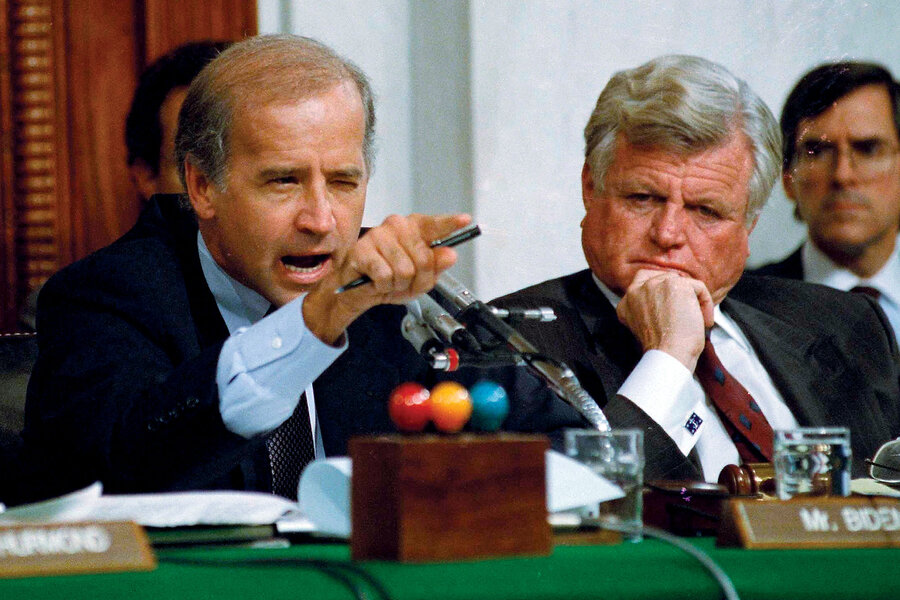

Then-Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Sen. Joe Biden points angrily at Clarence Thomas during his confirmation hearing for the Supreme Court, on Capitol Hill, Oct. 12, 1991. Sen. Edward Kennedy sits on his left.

But for Mr. Biden, and the nation, the lessons of the Hill-Thomas hearings reverberated. The election of 1992 became the “year of the woman,” with record numbers of women winning Senate seats. Today, Mr. Biden has made promoting women and people of color a centerpiece of his administration, including Vice President Harris. He touts a Cabinet that “looks like America,” with more women and people of color than any previous Cabinet. The Biden administration has seen more Black women confirmed to federal judgeships than any previous administration, including the first Black female Supreme Court justice, Ketanji Brown Jackson.

Eleanor Smeal, a longtime feminist activist who has known Mr. Biden since the 1980s, says he’s always been a champion for women. In the Anita Hill episode, she says, it was the Republicans on the committee who sought to discredit Ms. Hill’s testimony, not Mr. Biden and fellow Democrats. In 1994, she notes, Mr. Biden was a strong proponent of the Violence Against Women Act, which he has called his “proudest legislative accomplishment” as a senator.

“All I can say is, he has been very, very strong on legislation when it counted,” Ms. Smeal says.

She also calls Mr. Biden strong on women’s reproductive rights, despite his personal opposition to abortion as a devout Catholic. In 1994, as Judiciary Committee chair, he presided over passage of legislation guaranteeing access to reproductive health clinics.

Another past position Mr. Biden has backed away from was his support for the 1994 crime bill, which in 2019 he called a “big mistake,” with its overly harsh sentencing guidelines that disproportionately affected Black Americans.

“He gets it about race and racism,” says Democratic pollster Celinda Lake, who worked on his 2020 campaign. “He’s also very comfortable around LGBTQ rights and gender issues, which weren’t even on the radar for people in the 1990s.”

Ms. Lake credits Mr. Biden’s adult grandchildren, with whom he is close, for keeping him up to date on trends and social issues. In 2012, Mr. Biden was famously a step ahead of his boss, President Barack Obama, in voicing support for same-sex marriage.

His latest foray into modern culture came last month on Super Bowl Sunday, when his campaign joined TikTok after saying it wouldn’t over national security concerns. Campaign advisers have said they’re intent on “meeting voters where they are” – though, notably, the president’s risk-averse White House press team declined to make him available for a Super Bowl pregame interview for the second straight year.

In general, the Biden team has limited his availability to reporters, holding many fewer press conferences so far (33) than Mr. Trump in one term (88) and Mr. Obama in two (163). Mr. Biden’s habit of misspeaking in unscripted moments is nothing new. But the optics today are far riskier.

President Joe Biden walks off Air Force One upon arriving at Duluth International Airport in Minnesota, Jan. 25, 2024.

America’s role in the world

Mr. Trump is of the same generation as Mr. Biden, and neither man served in the military, each having received multiple draft deferments during the Vietnam War. But they have diametrically opposite views on America’s role in the world.

Mr. Biden’s worldview is centered on the internationalist tradition, defending freedom around the world, while Mr. Trump’s posture is that of an “America First” strongman ready to abandon traditional alliances, including NATO.

In his early Senate days, a young Mr. Biden served with many World War II veterans who instilled in him a reverence for military service, regardless of party affiliation. Later, he bonded with Vietnam War vets. The late Republican Sen. John McCain became one of his dearest friends, and today, Mr. Biden and former Senator Hagel remain close.

“When the World War II generation left the scene, in the House and Senate, that created an amazing vacuum,” says Mr. Hagel, who was secretary of defense under Mr. Obama. “I don’t think we even understood what we lost when we lost these people.”

Mr. Hagel says he’s still a Republican, “though I’m not sure why.” He plans to campaign for Mr. Biden. And he acknowledges that the president faces an extraordinary challenge over the Israel-Hamas war, including at home politically.

The former senator notes the importance of the Arab American vote in Michigan – a key electoral battleground state and home to the nation’s largest Arab community. Last month, top White House officials traveled to suburban Detroit to meet with Arab Americans and hear them out.

Mr. Biden’s deep devotion to the state of Israel, going back decades, remains one of those bedrock views that he’s having to weigh against the current state of affairs.

Mr. Kaufman, his longtime friend, explains the Biden love of Israel simply: “It’s because he’s Irish. The Irish have a concern for the underdog, especially Irish Catholics.”

Today, Mr. Biden himself appears to be an underdog in a campaign he describes in existential terms for the nation’s future.

But the race is still young.

Staff writer Caitlin Babcock contributed reporting from McLean, Virginia.

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : The Christian Science Monitor – https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Politics/2024/0304/Joe-Biden-faces-the-test-of-a-lifetime?icid=rss