The girl with the ponytail and overalls has four favorite sports.

“Fútbol, básquet, béisbol, y fútbol americano,” she tells her class in Spanish, seated in a circle on a rug.

A new teacher at Eagleton Elementary in Denver tells the class it will practice English tomorrow. But a cluster of kids can’t wait.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused on

In an election year where immigration is a top issue, how are public schools managing a sharp rise in students?

“¡Ahora!” they say, wanting to try now. New words trickle in through their ears and transform out their mouths. Fútbol becomes soccer. Béisbol turns into baseball.

This New Arrivals class, for English learners in kindergarten through third grade, is itself new. In January, soon after a migrant shelter opened nearby, the school of 212 students added another 125. Most come from Venezuela, where political and economic crises have caused millions to flee.

“When you have 17 kids in your classroom, and then the next day you have 35, you’re basically starting over,” says Janine Dillabaugh, the principal. Beyond academic support, she says, “we also have to attend to their social and emotional needs.”

In an era of historic migration globally and at home, many Americans rate immigration as a top policy issue ahead of the 2024 election. Yet like the United States itself, public schools have long welcomed foreign-born newcomers. Students in the U.S. have a right to a public education no matter their immigration status.

Districts of all sizes across red and blue states are finding that the sudden increase of new arrivals has challenged their current capacity. An increase in newcomer student enrollment after annual funding deadlines have passed, for example, has raised questions around staffing amid existing strains. Still, despite these challenges, many educators embrace an approach that sees these students as assets. They view these learners as multilingual contributors to their communities – and, one day, the economy.

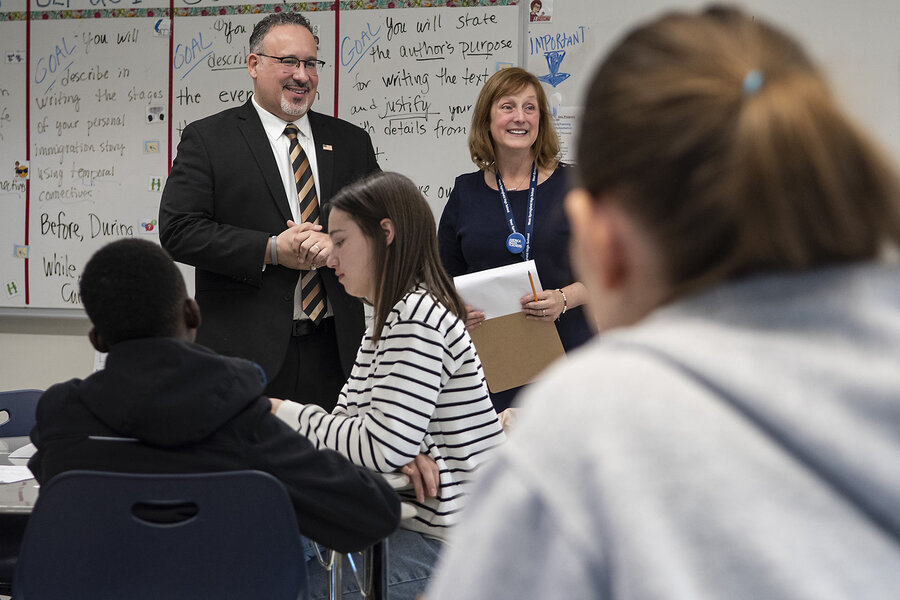

That was the thrust of Education Secretary Miguel Cardona’s message last month when he visited a high school in West Springfield, Massachusetts, which is experiencing similar growth. Of the school’s roughly 130 multilingual learners, around half enrolled throughout the current school year, though the district says many have since left the area due to high housing costs.

“We need to do more,” Secretary Cardona tells the Monitor. “The beauty is we have a lot of bilingual students in our classrooms. So how are we creating pathways for them to become the next teachers?”

Back in Denver, Ms. Dillabaugh, the Eagleton principal, says she’s seen the majority of these newcomers arrive “smiling and super excited and totally willing” to jump in.

That joy is evident in the New Arrivals class, where music signals a break. Students hop around in delight, high-fiving friends. The teacher gets a high-five, too.

Beyond a “crisis” narrative

Pandemic disruptions and reporting lags in enrollment data make quantifying newcomer students difficult. Among some 49.4 million students attending public schools during the 2021-2022 school year, the most recent federal data available, roughly 1 in 10 students were English learners.

In 1982, the Supreme Court ruled in Plyler v. Doe that states can’t deny students access to public elementary or secondary schools based on immigration status. The Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015 further defined equal access to quality education for English learners.

Schools, then, become the de facto entry point into American society for many of these children. That’s why experts emphasize the need to build community among students.

“Having them feel like they belong to school is important,” says Delia Pompa, a senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute.

Welcoming newcomers involves perception shifts, says Tania Hogan, executive director of the BUENO Center for Multicultural Education at the University of Colorado Boulder. Beyond a “crisis” narrative, she encourages schools to recognize possibilities.

Newcomers offer a “wonderful opportunity to learn a different culture, language, different perspectives,” says Dr. Hogan. For example, some students may have firsthand knowledge of rainforests or other topics taught in class.

Multilingual learners participate in an English class at West Springfield High School, March 14, 2024, in West Springfield, Massachusetts.

Justin Cohea, who teaches high school in Modesto, California, sees the beauty and difficulty of serving newcomer students daily. He recently observed how defeated a student looked when her bilingual aide was out. Not a fluent Spanish speaker himself, Mr. Cohea recognized that his support alone wasn’t enough.

But he also notices the bright spots. A group of students from different cultures congregated in his classroom during lunch last year, celebrating birthdays and sharing food from their native countries.

“It was really a special time,” he says.

Funding stressors

In communities welcoming an unexpected increase of newcomer students, however, the challenge often boils down to human capital.

Are there enough teachers to staff growing schools? What about bilingual aides or educators? And does the school employ counselors or social workers who can help children acclimate, particularly after trauma they may have endured?

The Department of Education has outlined $940 million, in the president’s budget proposal for fiscal year 2025, that would support English learners. (That would be a $50 million boost from the latest fiscal year.) The federal government has also reminded states that leftover pandemic aid can support immigrant students before a funding deadline this fall.

“It’s certainly not enough,” says Ms. Pompa of the Migration Policy Institute. Most district funding, however, typically comes from local and state dollars.

Newcomer students and multilingual learners are two distinct but overlapping groups, she says. In many cases, the funding approved is merely a “political kind of compromise,” and doesn’t account for recent arrivals.

Costs appear especially concerning to conservatives. The Heritage Foundation encourages states to pass legislation that would charge tuition for unaccompanied minors, as well as students whose parents are in the country unlawfully, to attend public school. That could relieve the “financial burden” on states and districts, says Madison Marino, a Heritage senior research associate. But the constitutionality of such legislation remains unclear.

“It’s the Biden administration’s unwillingness to secure the border,” says Ms. Marino, that’s created “mounting challenges for schools across the country.”

Families make up 39% of all Border Patrol encounters along the southern U.S. border since the fiscal year began in October. Some immigrant students enter the U.S. illegally. But many arrive with their families through lawful pathways, including the Refugee Admissions Program, which is rebounding after cutbacks during the Trump administration and pandemic.

Massachusetts is among the states trying to ease the burden on school districts by sending money their way. The state offers districts around $105 per day per eligible student housed in emergency shelter, with additional grants of $1,000 per student available. Many newcomers in West Springfield Public Schools are homeless.

Born in Peru to Haitian parents, Macarena, whose last name the Monitor agreed to omit for privacy, sleeps on a couch next to her 2-year-old brother in a hotel room without a kitchen.

The second grader, who glides between English and Spanish, has several favorite parts of school: homework, spelling, tests. Plus, “I have lots of friends to speak with me” and play hide-and-seek, she says. Her favorite English word, in fact, is “friends.”

U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona stands next to teacher Kelly Gilmore as he visits an English class for multilingual learners at West Springfield High School, March 14, 2024, in West Springfield, Massachusetts. Dr. Cardona met with students and teachers and led a roundtable discussion on career-connected learning with local leaders.

“Knowing more than one language is a superpower,” Dr. Cardona tells a class for English learners at West Springfield High School. “Raise your hand if you agree.”

They do. And when Dr. Cardona slips into Spanish, a boy in the back of the room smiles.

“Continue learning English, continue learning about one another, and continue to maintain your native language,” says Dr. Cardona, once an English learner himself. An American flag hangs behind him on the wall.

Solutions for staff and students

Getting students to that “superpower” status takes time, staffing coordination, and a little ingenuity.

The Springfield City School District in southwest Ohio has been grappling with this challenge after welcoming hundreds of children from Haiti in recent years.

The 7,400-student district employs five bilingual assistants who speak Haitian Creole and six who speak Spanish.

But bilingual assistants can’t do it alone.

District leaders have prioritized hiring educators who are credentialed to teach students who speak a different language. Even if not bilingual, they can deploy strategies to help newcomer students. Meanwhile, the district has partnered with Xavier University in Cincinnati to help existing teachers receive that credential.

“We’re just hoping that we can build the capacity in the toolboxes of our teachers that teach science and social studies and math to be as effective as they can be for the students that are sitting in their classrooms,” says Kaylin Hunsaker, coordinator of state and federal programs for the Springfield City School District.

Next year the district plans to go a step further by launching a dual-language program. Students in the kindergarten and first-grade pilot classrooms will spend part of the day learning in Spanish and the other half in English. In time, the district envisions the program expanding into other languages, Ms. Hunsaker says.

As a stopgap, some students and staff are called on to interpret in a newcomer’s native language. But advocates say that’s not a long-term solution.

“It is unfair to put that on the shoulders of another student or a school secretary or another educator,” says Keri Rodrigues, president of the National Parents Union.

At Herriman High School in Utah, senior Sebastian Panayides is one of those students stepping up – and willingly. As president of a school group called Latinos in Action, Sebastian joins fellow multilingual peers in classrooms throughout the district, where they tutor younger newcomers in English.

Originally from Venezuela, Sebastian says mastery of two languages makes him “feel way ahead of the game.” As an English learner he used to loathe language arts. Now he journals almost every day.

Sarah Matusek/The Christian Science Monitor

Marian Alvarez, a new student at Herriman High School in Herriman, Utah, sits in the library after school, Feb. 7, 2024.

He models a transformation attainable to others, like fellow senior Marian Alvarez. The soft-spoken aspiring actor admits her first week at the Utah high school was difficult.

“I would come home crying because I didn’t understand anything,” says the Venezuelan student.

“Eventually I started to get the hang of it, and I’m better now,” she says in Spanish after school. While making friends has been hard, she says teachers have been kind.

“I love school”

Approaches to serving newcomers differ by school and district. But education and immigrant experts generally agree staff should strive to learn about each student’s strengths, build programs to support their needs, and engage their families. One Las Vegas model emphasizes the well-being of the entire family, not just the student.

Jackie Valley/The Christian Science Monitor

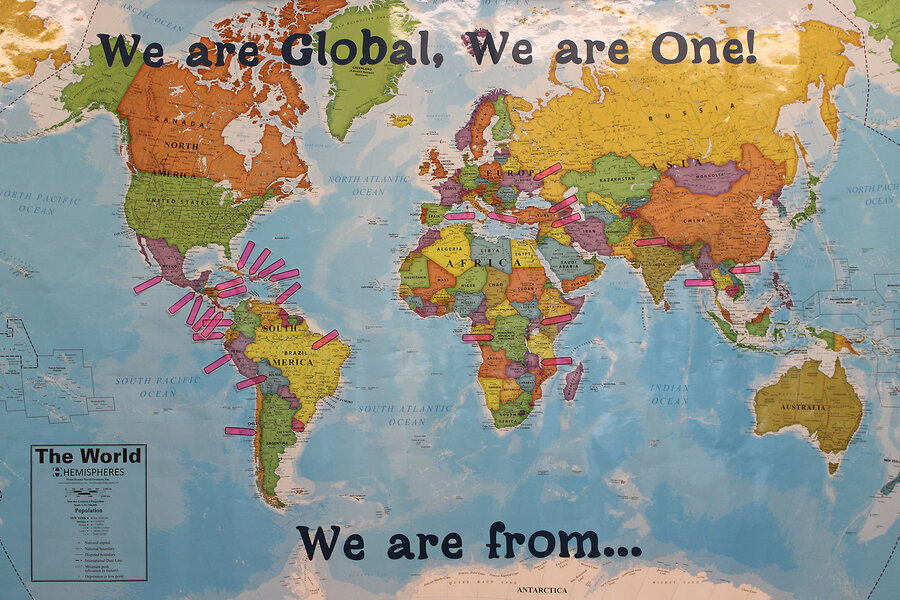

Students from Latin America, Africa, Asia, and Europe learn alongside each other at Global Community High School in Las Vegas. The school serves about 250 newcomer students, whose native countries receive an arrow on this map.

At Global Community High School, 250 students – from countries including Cuba, Mexico, Syria, and Thailand – sit side by side in classrooms as they acclimate to the U.S.

Across the street from the high school sits another modern, sleek-looking building. It’s the Clark County School District’s Family Support Center. The one-stop shop provides assistance with school registration, community resources, legal help, medical care, and adult English classes.

“We’re giving them that trust that they’re able to come,” says Astrid Silva, director of the district’s Undocumented and Immigrant Family and Youth Success Services, which is housed within the Family Support Center.

Likewise, immigrant parents have expressed gratitude for public schools, which they see as a stabilizing force in their children’s lives.

In Denver, one grateful parent, a Venezuelan asylum-seeker, recently found an apartment to rent with friends near Eagleton Elementary.

The mother, whose name the Monitor agreed to omit for privacy, says it’s important that her daughter continues kindergarten at the school after their stay at the nearby shelter ended. On their journey north via Mexico, the woman says her daughter survived a kidnapping attempt only after the child fell sick.

Sarah Matusek/The Christian Science Monitor

A Venezuelan asylum-seeker and her daughter in kindergarten reunite after school in Denver, March 11, 2024.

Afterward, her daughter “had become a little more rebellious. But now that she’s at school, it’s stopped,” she says in Spanish. “It seems she wants to communicate, above all, in English.”

And so her daughter does, once reunited with her mom on the sidewalk after school. She’s shy but offers a few words, just above a whisper.

In English, she says, “I love school.”

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : The Christian Science Monitor – https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Education/2024/0417/public-schools-education-immigration-southern-border?icid=rss