Mona Lisa is the world’s most famous painting by Leonardo da Vinci. It was painted between 1503 and 1519 and now hangs in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

Scientists have been poring into Leonardo da Vinci’s writings and artwork in quest of hints because of the aura of mystery surrounding the paints and pigments in his studio. Many works of art from the early 1500s, such as the “Mona Lisa,” were painted on wooden panels that needed a substantial “ground layer” of paint before any additional artwork could be added.

New analyses published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society show that his taste for experimentation extended even to the base layers underneath his paintings.

Using high-angular resolution synchrotron X-ray diffraction and micro Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, scientists analyzed an exceptional micro-sample from the ground layer of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Surprisingly, samples from the “Last Supper” and the “Mona Lisa” indicate that Leonardo may have experimented with lead(II) oxide, causing a rare substance called plumbonacrite to form beneath his works of art.

Scientists have discovered that whereas other artists frequently employed gesso, da Vinci experimented by applying thick layers of lead white pigment and by incorporating lead(II) oxide. This orange pigment gave the paint above particular drying properties. On the wall underneath the “Last Supper,” he used an identical technique, departing from the conventional fresco method in use at the period.

Victor Gonzalez and colleagues intended to use modern, high-resolution analytical methods on small samples from these two paintings to study these distinctive layers better. They performed their analyses using X-ray diffraction and infrared spectroscopy techniques. They determined that the ground layers of these artworks not only contained oil and lead white but also a much rarer lead compound: plumbonacrite (Pb5(CO3)O(OH)2).

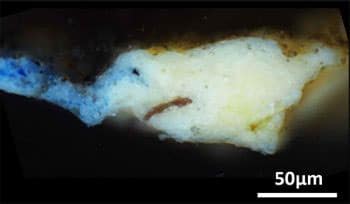

This tiny fleck of paint, taken from the “Mona Lisa” is revealing insights into previously unknown steps of the artists’ process. Credit: ACS

This tiny fleck of paint, taken from the “Mona Lisa” is revealing insights into previously unknown steps of the artists’ process. Credit: ACS

Even though it had been discovered in later Rembrandt paintings from the 1600s, this substance had previously yet to be seen in Italian Renaissance artwork. Because plumbonacrite is only stable in an alkaline environment, it is likely to have resulted from a reaction between lead(II) oxide (PbO) and oil. In most samples recovered from the “Last Supper,” intact grains of PbO were also discovered.

Although lead oxides were frequently added to pigments by painters to speed up the drying process, this method has not been empirically verified for works by Leonardo da Vinci. Even though PbO is now recognized as very harmful, the researchers who went through his papers only found references to it when discussing skin and hair cures. These findings show that lead oxides must have been on the ancient master’s palette and may have contributed to the creation of the works of art we know today, even if he may not have recorded it.

Journal Reference:

Victor Gonzalez, Gilles Wallez, Elisabeth Ravaud, et al. X-ray and Infrared Microanalyses of Mona Lisa’s Ground Layer and Significance Regarding Leonardo da Vinci’s Palette. Journal of the American Chemical Society. DOI: 10.1021/jacs.3c07000

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : Tech Explorist – https://www.techexplorist.com/mona-lisa-revealed-another-secret/75423/#utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=mona-lisa-revealed-another-secret