In King Charles III’s new official portrait, the monarch is depicted amid a sea of red with a butterfly near his shoulder. Its debut sparked discussion around the world: Was the striking color meant to be about his legacy? A statement about the Crown’s past? Is maximalism a ploy to distract his subjects?

Speculation abounds, but this reaction is nothing new. As long as portraits and images have existed, they’ve been created with purpose and symbolism, inviting controversy and trouble.

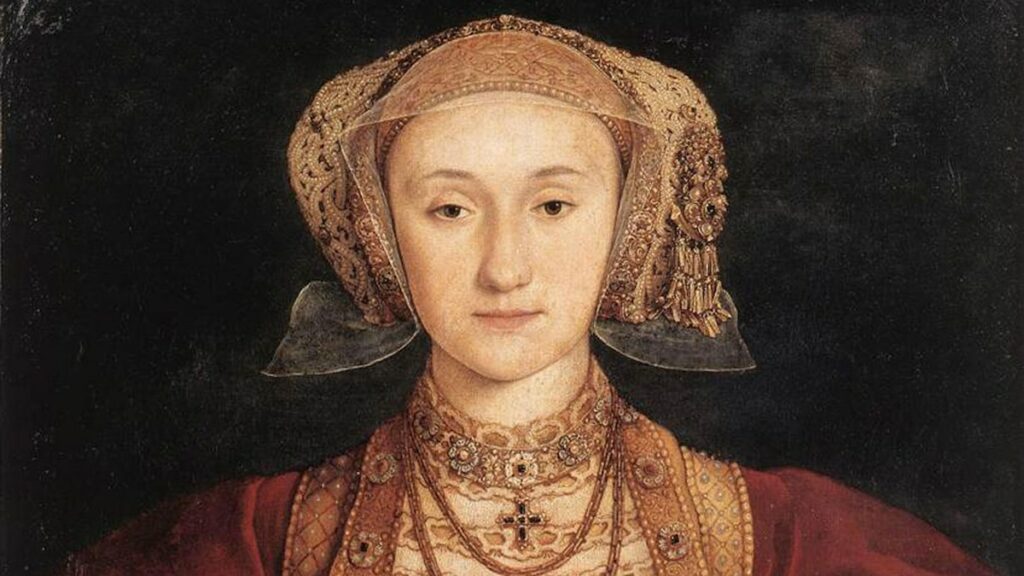

Anne of Cleves

The portrait j painted of Anne of Cleves purportedly helped convince Henry VIII of England to marry her, his fourth wife, on January 6, 1540.

In 1539, Henry VIII dispatched an entourage to the Duchy of Cleves (in modern Germany) to meet with Anne’s brother, Duke Willhelm. In need of a political ally, Henry was eager to marry Wilhelm’s sister but wanted to see what his future bride looked like. Alongside the famous Holbein portrait, Henry’s advisor Thomas Cromwell was told Anne was beautiful and the King was told she was ideal for bearing him more children given her “convenient age, healthy temperament, elegant stature… and other graces.”

When Anne arrived in England, Henry was anything but pleased. “She is nothing fair. Her person is well and seemly, but nothing else,” he said, apparently adding he wouldn’t have married her at all had she not made the trip to England and if he didn’t fear she would marry one of his enemies.

While he did marry Anne, their marriage lasted only a few months. Because their marriage was never consummated, it was annulled on July 9, 1540.

Winston Churchill

Visitors admire Karsh’s portrait at the Hungarian National Gallery.

Photograph by Ritter, ullstein bild, Getty Images

It’s perhaps the most famous photo ever taken of Winston Churchill, and it’s one that sparked the prime minister’s anger. While Churchill was in Canada in 1941, photographer Yousuf Karsh was given one opportunity to take a picture of the British statesman.

According to Karsh, “Churchill’s cigar was ever present. I held out an ashtray, but he would not dispose of it.” Karsh walked back to his camera and waited for Churchill to take the cigar out of his mouth willingly.

After several moments, Karsh, “stepped toward him and, without premeditation, but ever so respectfully, I said, ‘Forgive me, sir,’ and plucked the cigar out of his mouth. By the time I got back to my camera, he looked so belligerent he could have devoured me. It was at that instant that I took the photograph.”

The photo ultimately captured Churchill in a moment that defined him for the ages.

Abraham Lincoln

In this print, the head of Abraham Lincoln is superimposed on the figure and background of an earlier print by A.H. Ritchie of John C. Calhoun.

Composite Print by William Pate-Courtesy Library of Congress

It took a century to reveal the famed portrait of Abraham Lincoln from 1852 wasn’t actually the 16th president of the United States. Amid modern discussions about photo manipulation by artificial intelligence, the portrait of Lincoln offered perspective on how easily an image can be changed.

Lincoln’s head, as it turns out, was affixed to the body of John C. Calhoun, one of the biggest pro-slavery champions in mid-19th-century American politics. As Harold Holzer, co-author of The Lincoln Image: Abraham Lincoln and the Popular Print, explained, “the John C. Calhoun portrait that morphed into a Lincoln portrait, flowing robes and all, Unionist replacing secessionist” was among the many “such prints [that] elevated Lincoln to the status of American deity.”

Leopold I

Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor (1640-1705), is depicted in this painting by Benjamin von Block in 1672.

Photograph by Pictorial Press Ltd, Alamy

While it’s not as apparent in many of the portraits of Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor, as it is in those of his kinsmen, the Habsburg ruler did have the jaw for which his family is known: now known as prognathism, the lower jaw sticks out in an extreme underbite.

Instead of highlighting what may have been an unpleasant physical feature (which has long been attributed to inbreeding), portraits of Leopold present him as somewhat glamorous and distinguished.

There are distinct aspects of Leopold’s appearance that are difficult not to notice. His big brown hair cascades down his shoulders, immediately leading the eye down to the mouth of the late 17th-century ruler. His plump, crimson lips in the portrait by Benjamin von Block are also set off by the red background and cape draping around him. Try as he might, von Block couldn’t hide all of Leopold’s features that earned him the surname “Hogmouth.”

Napoleon

Jacques-Louis David’s first version of Napoleon Crossing the Alps.

Photograph by Artepics, Alamy

Using an image of a ruler for propaganda didn’t start with Napoleon Bonaparte, but his artistic panegyrist, Jacques-Louis David, may have mastered the craft. His painting, five versions of which were made between 1801 and 1805, all feature Napoleon upon a noble steed in full general garb pointing up and onward. The cloak upon his shoulders changes from painting to painting, as does the color of the horse, but the glorification of the emperor as he crosses the Alps remains consistent.

Napoleon Crossing the Alps drew upon artwork associated with the likes of Peter the Great, evoking his military prowess with one glance. Napoleon refused to pose for the portrait, telling David, “no one knows if portraits of great men are likenesses: it suffices that genius lives.” In the end, Napoleon was right. The legacy of his achievements has undoubtedly mixed fact and myth, ultimately influenced by the work of artists like David.

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : National Geographic – https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/portraits-controversy-charles-churchill-lincoln-napoleon