Jessica Bearnot-Fjeld stands at her kitchen island, slicing green apples for an afternoon snack. Her two young children, just off the school bus, scan the cupboard for Nutella as a spread, but they come up short. No Nutella. “We ran out. Put it on the list,” Ms. Bearnot-Fjeld tells Tabitha, age 6.

Her son, Winfield, 8, reaches for the peanut butter. He’s in second grade at the same elementary school that Ms. Bearnot-Fjeld attended in this town of 4,000, to which she moved back last summer with her husband, a physician. Her sister is the school librarian and has two kids of similar age to their cousins.

Two families, four children. It’s a typical story of modern American family formation, of an ever-expanding population, each generation on average more affluent and living longer than the last.

Why We Wrote This

The decision to have a child is deeply personal. But individual choices have ripple effects. In the United States and beyond, declining birthrates are triggering societal shifts.

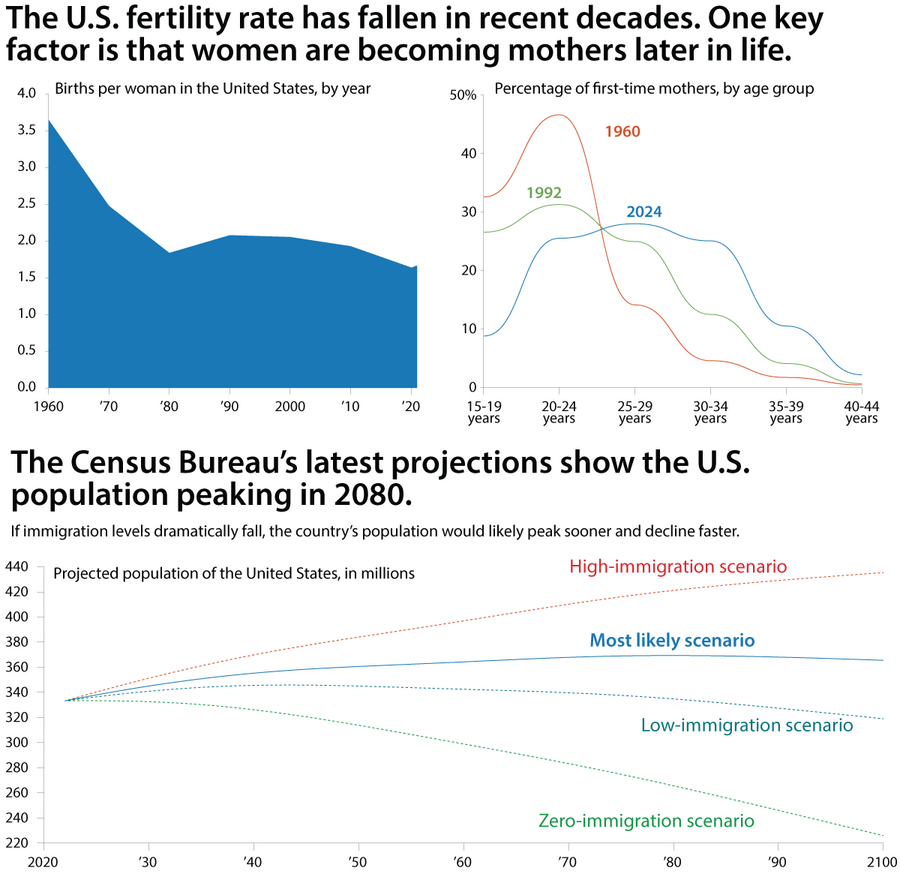

But Ms. Bearnot-Fjeld’s family size is not as average as it appears. In fact, it’s well above average for her generation, one born in the 1980s that came of age in a new century and ran headlong into the 2007-09 recession. Since then, birthrates have slumped by 20%, putting the United States on a path of population decline, similar to the dropping birthrates in other rich nations.

Of all the political and social debates roiling the country, the decline in childbearing may prove the most momentous and far-reaching, even if it doesn’t present as a crisis today. The topic is intensely personal but also shapes our collective future, one in which children are no longer as abundant and the voices of childless people matter more.

Simply put, women in the U.S. are having fewer children, whether by choice or by circumstance, or deciding not to have any at all. The reasons for the slowdown are complex and don’t yield easily to empirical analysis. Nor is it clear that pro-natal government programs can reverse the trend, given the modest effects of such policies in other countries grappling with low fertility.

Some experts blame the economic pressures on families and the uncertainty couples face when trying to budget for a growing family. “People are waiting for a good time to have a kid, and the good time never seems to come along,” says Sarah Hayford, the Institute for Population Research director at Ohio State University.

Others say these economic stresses, while real, don’t fully explain the slowdown in births, adding that changing social norms mirror what’s already happening in Europe and Asia. Hands-on, time-intensive parenting may be reshaping ideals of family size. And priorities have also shifted: In a 2023 Pew Research Center survey, most American adults said that enjoying their work ranked higher than having children in “living a fulfilling life.” Only 26% said having children was extremely or very important to them.

“Young people, as they move to childbearing age, are looking for something different in their life experiences than they did historically,” says Phillip Levine, an economist at Wellesley College who studies fertility rates. “People are making different choices.”

Lowest population growth since the 1930s

The effects of these choices are already being felt. In 2020, the decennial U.S. census recorded the second-lowest decade of relative population growth since the first census was taken in 1790. Only the 1930s, roiled by the Great Depression, saw a slower growth rate.

Had the U.S. birthrate stayed the same between 2007 and 2022, an additional 9.6 million children would have been born over that period, demographers estimate. Instead, these smaller cohorts will be the workforce that shoulders the fiscal burden of retirement by older generations. By 2028, 1 in 5 Americans will be age 65 or older.

The fall in births has also forced demographers to redraw projections. In 2012, the Census Bureau predicted the U.S. population, then at 313 million, would reach 420 million by 2060. Last year, the bureau released new projections in which the population would start to decline this century because of lower fertility rates unless immigration increases. Its new forecast for 2060 is 364 million, a shortfall of 56 million people, or more than the current combined populations of Florida and Texas. The current U.S. population is 336 million.

SOURCE:

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Census Bureau

|

Jacob Turcotte/Staff

Similar recalculations are happening globally: Analysts say the world population, currently 8 billion, may peak as early as the 2060s, then fall exponentially as families shrink. In fact, some population experts say global births per year already peaked in 2014 – and will never be as large again.

Some have cheered the prospect of population deceleration on a finite planet scoured by resource extraction, saying fewer children would allow wealth to be spread more evenly. Some climate activists embrace low population growth as a boon for the environment.

But the timing doesn’t add up for addressing climate change, given that emission cuts must happen now and be sustained to avert future catastrophic warming. “We’re not going from 8 billion to 4 billion in the next 30 years,” says Professor Levine.

Like most economists, Dr. Levine doubts that a shrinking population would help over the long run as much as one that is growing. An aging society with fewer working-age adults also faces a short-term squeeze in funding public health and pension programs.

Cars weave down Center Street in Brandon, Vermont, Feb. 5, 2024. While births across the country have been declining, Vermont has the lowest birthrate of all of America’s 50 states, according to the CDC.

To Lyman Stone, a demographer at the Institute for Family Studies, a conservative think tank, the strain on public finances distracts from more profound questions raised by falling birthrates. He worries about what a baby bust portends for personal and shared aspirations and about what happens to societies in an era of fewer children and generational detachment.

“My concern is what happens to us as people when we become a society of … foreshortened hopes in an area [childbearing] that is central to human life and human culture,” he says.

Balancing work and family life

Ms. Bearnot-Fjeld grew up as the eldest of four children. Her parents came from big families, and her cousins often came over, adding to the hubbub. “I remember we used to pick up the landline phone, and my dad would answer it, ‘Grand Central Station,’” she says. “It was a very happy, full life.

To her, four children seemed ideal. But life didn’t quite work out that way.

Ms. Bearnot-Fjeld studied poetry as an undergraduate, worked in publishing in New York, and then did a master’s in poetry before deciding to switch to law. At Columbia University, she met her future husband, a medical student. A year after their wedding, they graduated and moved to Boston for work. They bought a condo and began trying to have a baby.

Two years later, their first child was born. “I remember looking at Winfield as a newborn and being like, ‘You’re going to be a great big brother,’” she says.

Tabitha arrived in 2017. By then, the burdens of parenting while working full time had punctured their aspirations. The couple considered having a third, but then came the pandemic.

“It made it really challenging to think about having a third child,” says Benjamin Bearnot-Fjeld, who grew up as one of three boys in his family and, like his wife, aspired to have “multiple children” of his own.

“That’s the point at which we closed the books,” adds Ms. Bearnot-Fjeld.

In 1970, the average first-time mother was 21. Ms. Bearnot-Fjeld was 32 when Winfield was born. As more women enter professions requiring advanced degrees and training, childbearing has shifted to later in life, which usually means smaller families, even with fertility treatments becoming more available.

Marriages are also happening later, if at all. While not all children are born to married couples, most still are; marriage remains a strong norm for childrearing for both men and women. So declining rates of young-adult coupling and of marrying – only one in two adults are currently married, a record low – act as a drag on birth rates as couples wrestle with life choices. “It’s not just about what women want. Men are involved in this decision too,” says Professor Levine.

Another issue, says Brad Wilcox, who directs the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia, is that women report difficulty finding men who seem able or willing to be good parenting partners, particularly in lower socioeconomic circumstances. “In today’s culture, a lot of teenage boys and young men are floundering, both in school, in college and the workplace, and so that affects their appeal when it comes to dating and marriage,” he says.

Surveys show that young women still aspire to have, on average, between two and three children, a hope that may go unfulfilled due to timing. “The age at which you have your first kid is strongly predictive of whether you’re actually going to hit your goal,” says Mr. Stone.

An economy that rewards highly educated workers who earn modestly in their 20s isn’t conducive to them having large families, he says. “If the life timeline does not allow young people to achieve a stable life until they’re 34, there won’t be a lot of babies.”

Declining births and replacement rates

For Ms. Bearnot-Fjeld, moving to central Vermont has relieved some of the pressures that put a third child out of reach. Her mother, Carol, can take the kids after school. Her sister lives down the road. She still lectures at Harvard, with a biweekly teaching schedule, and works remotely in the Victorian house the couple rents from family friends. “I played here as a kid,” she laughs.

Carol Fjeld talks about her family during an interview with the Monitor Feb. 5, 2024, at her daughter Jessica’s home in Brandon, Vermont. Vermont has the lowest birthrate in the United States, according to the CDC.

While her two children put her above the U.S. average of 1.6 children per woman, in Vermont, she’s even more of an outlier. The Green Mountain State has the lowest birthrate of all: 45 births per 1,000 women of childbearing age (15 to 44 years old), compared with a national average of 56, and a high in South Dakota of 69 births.

To stay constant, a population requires an average of 2.1 children per woman, a ratio known as the replacement rate. Some two-thirds of people already live in countries at or below that level. In East Asia, Taiwan and South Korea are closer to one child than two.

Advocates for pro-natal policies say the U.S. could copy countries that invest more in childbearing since society has a collective interest in supporting parents, says Karen Guzzo, director of the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina. But such policies aren’t a fix for sliding birthrates. “We know there’s always a lag between economic and policy changes and when people feel them and acknowledge them,” she says.

Skeptics note that Scandinavian countries with generous child benefits and egalitarian parenting still have declining birthrates. Finland’s fertility rate has fallen by a third since 2010. And the kinds of programs debated in the U.S. Congress, such as expanded tax credits, pale when compared with incentives proffered to parents in Europe and Asia.

Still, Mr. Stone says fertility rates would be even lower without pro-natal policies in countries like South Korea, which recorded 250,000 births in 2022. At its current rate, its population would be halved to 24 million by the end of the century. “It’s the lowest in the world. It could go lower,” he adds.

Why the birthrates are falling

Inside a steakhouse in Hanover, New Hampshire, Jessica’s sister Kalle Fjeld scans the dinner menu. She just finished a 12-hour shift at the Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center where she’s in her third year of residency in the emergency department. Like her sister, Ms. Fjeld took a zigzag path to her career, including a post-college year teaching in France and a stint as a pastry chef, before starting medical school at age 27.

Baking is just a hobby now. That day, she woke at 4 a.m. and made scones to bring to work. Whenever she brings in food or sews a quilt for a co-worker, she hears a familiar refrain: “Oh, you’ll be a great mother.”

But Ms. Fjeld is single and has no plans for motherhood.

Kalle Fjeld, a resident physician at Dartmouth, poses at the farm where she boards her horse, Mr., Feb. 10, 2024, in Brandon, Vermont.

Her hours in the emergency department are long and can involve stressful, life-or-death decisions. When she has downtime, she likes to cook and ride her horse, which she stables an hour’s drive away. Where she lives, “it’s not easy to date,” she says.

Once she’s completed her medical training, Ms. Fjeld knows her work-life balance as a doctor will improve. Perhaps then, marriage and motherhood would be an option. But “investing the time needed to build on that now is a low priority for me,” she says.

Most young people don’t enter professions like medicine and law in which the traditional milestones of marriage, homeownership, and childbearing arrive later. Why, then, are birthrates falling among Americans at all income levels?

One reason, says Professor Guzzo, is that non-college graduates are adopting the same social norms – and scrolling the same social media feeds – as those trying to finish multiyear academic and professional training. Across the board, the message seems to be: Don’t have children until you’re ready and can provide a good life.

But they also see how much child care costs and are less likely to have paid parental leave or a solid career path, which can discourage starting a family. “Those are the folks I think we’re failing because [they] say, ‘I want to have children, too.’ But they don’t see a predictable future in which they will fulfill those prerequisites,” says Professor Guzzo.

Like her sister, Ms. Fjeld has halcyon memories of growing up in small-town Vermont and being part of a large family. When she does picture having children, she pictures two or more, never one.

She’s thrilled that her two sisters are raising their kids in Brandon so she can see them regularly. Of her siblings, she’s the only one not to marry. Her brother lives in Austin, Texas, with his wife, who is pregnant with their first child. Above all, she loves being an auntie, she says. “I get to have kids around me without having kids.”

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : The Christian Science Monitor – https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/2024/0327/US-parents-are-having-fewer-children-later.-What-it-means-for-society?icid=rss