History remembers Genghis Khan in two distinct ways: a ruthless conqueror and founder of the largest contiguous empire to ever exist. In 1206 Genghis Khan achieved what many other conquerors could not by bringing all the Turco-Altaic peoples of the Mongolian Plateau under his authority. Subduing these people, known as “those who live in felt tents,” was only the beginning. The first great khan of the Mongol Empire was a military genius who drove his armies to expand territory, adapt rapidly, and fight with endurance.

Genghis Khan’s empire continued to spread across Asia, sweeping away preexisting states. In the east, the Mongols destroyed the kingdoms of the Jurchen and the Tangut in modern-day China, while to the west they crushed the Khitan and the Khorāsānians of Transoxania in Central Asia. The latter had defied the Mongols by providing refuge for traitors and nomads fleeing their forces.

(She was Genghis Khan’s wife—and made the Mongol Empire possible.)

In 1223 the Mongols planned to conquer the Turkic herdsmen of the far western plains north of the Caspian Sea and the Black Sea. Genghis Khan relocated two of his best generals, Jebe and Subutai, from Persia, which he was in the final stages of conquering, to the Eurasian steppe. There Jebe and Subutai led 20,000 soldiers against the last remaining nomadic herders, the Cuman-Kipchak.

As soon as he heard of the imminent Mongol attack, Köten, the leader of the Cumans, asked for help from Kyivan Rus, a vast East Slavic state formed at the end of the 10th century around its capital, Kyiv. The Slavs and Cumans assembled a combined army of 80,000 men.

The Mongols, seeing they were outnumbered, gambled on deception. Subutai marched to meet the Slav-Cumanian army with 2,000 poorly equipped horsemen under orders to feign panic and flee. The ruse fooled the defending forces, who rode for nine days in close pursuit of the “panicked” Mongols. When they reached the Kalka River, near present-day Mariupol in Ukraine, Jebe and the rest of the Mongol army were waiting for the Slav-Cumanian army and crushed them. This was the first Mongol victory on European soil.

Postponed plans

The incursion into Europe was, however, an isolated one. The Mongol generals were ordered to redeploy and join Genghis Khan in his conquest of northern China some 3,700 miles away. The mission would drag on for several years. It wasn’t until 1235 that Ögödei, Genghis Khan’s son and successor, ordered a new offensive westward. Ögödei wanted to subdue the Cuman people and their allies once and for all.

(The Great Wall of China’s long legacy.)

Ögödei had taken over as great khan upon Genghis Khan’s death in 1227. He assembled an army of 100,000 horsemen, a much bigger force than his father had mustered 12 years prior. Although this army was led by chiefs from the four branches of the imperial family, military leadership formally fell to Subutai, who by then was an old man.

Ögödei, Genghis Khan’s son and successor, in a portrait.

Album

Subutai, shown in a 16th-century Chinese drawing, led the campaign that destroyed the armies of Europe.

AKG/Album

Ögödei employed Batu Khan, one of Genghis Khan’s grandsons, to lead the push westward across Europe in 1235. The Mongols entered through the upper Volga region and defeated the forces of the Cuman, the Alan, and the Bulgar peoples. Then they attacked Kyivan Rus again. At the end of 1237, the first great Russian fortress, Ryazan, fell after a six-day siege.

Batu Khan and his forces swept through the cities of Kyivan Rus. They fell one after another, including Kyiv, which was conquered at the end of 1240 after a nine-day siege. Known for incorporating the military knowledge of their captives, the Mongols employed Chinese siege engines as well as flammable liquids and gunpowder—the first time such techniques had been used in Europe.

(Who were the Mongols?)

Conquests and slaughter

European sources recorded that the Mongols massacred the inhabitants of each city they conquered, only leaving alive those they could use as forced labor. Thirteenth-century historian and eye-witness Thomas of Spalato (Split, Croatia) wrote in Historia Salonitana that in one town they left “nobody to piss against a wall.” The Cumans suffered devastating losses—more than 100,000 people. The Mongols allegedly calculated the figure by slicing an ear off each of the dead enemy soldiers and counting them up. As had happened almost two decades earlier, Köten, the Cuman leader, eluded Subutai’s sword and escaped. This time, Köten and some 40,000 survivors found refuge at the court of Hungary’s king, Béla IV, who held power from 1235 to 1270.

Slavery in Europe

The Mongols take captives from Galicia and Volhynia in an engraving from a 1488 Hungarian chronicle.

Bridgeman/GTRES

One of the effects of the Mongol conquests was an increase in the Eurasian slave trade. When cities were defeated, the Mongols either massacred the inhabitants or sold them into slavery. Like livestock or foodstuffs, people were seen as a valuable commodity in the Golden Horde, the Mongol state created by Batu Khan that became a major provider of enslaved labor. People enslaved by the Mongols were sold in major slave markets that supplied Mediterranean ports with people destined for domestic service, sex work, or military service. Some were valued as elite for their jobs, military knowledge, or status prior to captivity.

From his base in southern Ukraine, Batu Khan sent a letter to Béla warning him of what would be in store if he didn’t hand over the Cuman fugitives: “For it is easier for them to escape than for you, since they are without house and move about in their tents, and so may perhaps be able to escape. But as for you, who dwell in houses and have fortresses and cities—how will you evade my grasp?”

King Béla IV, leader of the Mongol resistance, in a 21st-century statue by Peter Gáspár in Banská Bystrica, Slovakia.

Azoor Photo/Alamy/ACI

However, King Béla didn’t bow to Batu Khan’s threat. Giving protection to the Cumans allowed him to present himself as an exemplary king. Sheltering the Cumans went hand in hand with assimilating them into Hungarian culture and converting them to Catholicism. Béla then requested military aid from other princes with a view of creating a capable army. This was attractive to Béla because it would be independent of the Hungarian feudal lords, with whom he was at odds.

The Hungarian people, on the other hand, feared the ire that the Mongols threatened and were much less favorable to the Cumans. Eventually, a mob whipped up by members of the Hungarian aristocracy managed to lynch Köten. After the assassination, Köten’s warriors fled south and west, destroying numerous Hungarian villages as they went.

If Béla expected solidarity from the other states, he was soon disappointed. The king tried to persuade Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II to send troops, even offering to become a vassal state. The Holy Roman Empire was a large confederation of states and smaller political entities, which made its leader Europe’s most powerful sovereign. Frederick II denied Béla’s request for help and praised the warlike qualities of the Mongols, who in his eyes were “tough, broad, sinewy, strong, bold, fearless, incomparable archers, and ready to defy any danger at a signal from their commander.”

Béla turned to the church, also imploring Pope Gregory IX to help and warning that if Hungary fell, nothing would stop the Mongol advance on Europe. The pope did proclaim a small Crusade against the Mongols, but no substantial forces were ever dispatched. The only firm commitment Béla obtained came from his cousin Henry II the Pious, the Duke of Silesia and High Duke of Poland, who was one of the most powerful lords in the region.

(Discover our Hungary travel guide.)

Unstoppable advance

Batu Khan and Subutai then organized one of the most effective and brilliant offensives in military history. Mongolian forces were divided in three units, each one advancing from Ukraine at the same time but taking separate routes toward their targets. They would break into European territory almost simultaneously at two points around 450 miles apart.

Apocalyptic visions

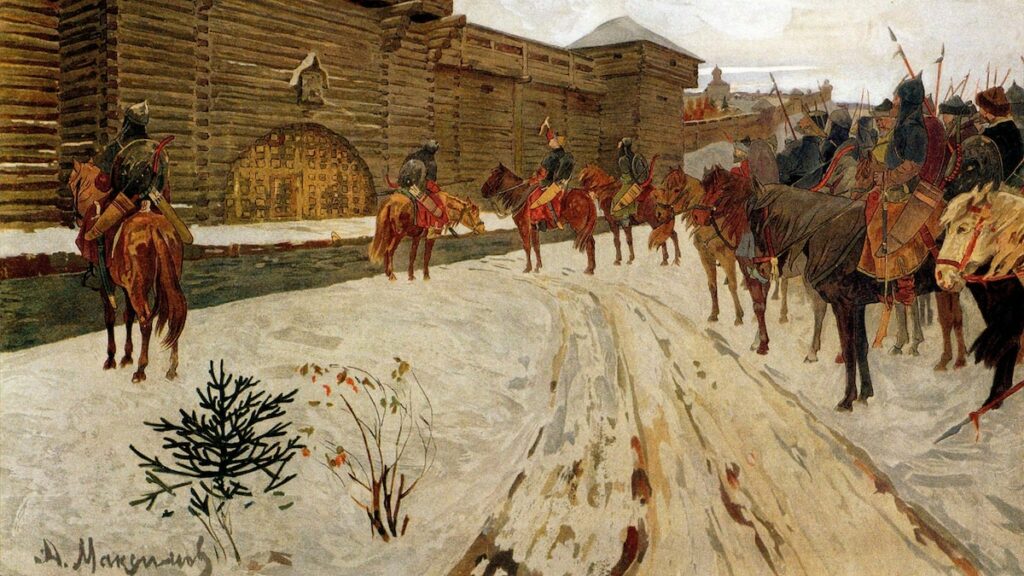

A Mongol army, featuring a horseman with a bow, rushes to conquer a Slavic city.

Getty Images

The lightning-speed expansion of the Mongol Empire shocked Europeans, prompting both bewilderment and horror. Lurid rumors proliferated about them: The Mongols were barbarians; they shunned religion; they ate the flesh of human beings. In actuality, the Mongols were not cannibals and were tolerant of their captives’ religions. While cruel in conquest, the Mongols were skilled warriors in battle, using their equestrian and archery skills to great advantage. But in 13th-century Europe, the popular imagination began to link the Mongols as a force of evil described in the Bible: Gog and Magog, who battle at the end of days. This apocalyptic lens explains why the term Tatars (or Tartars), previously used for nomadic peoples of west-central Russia, was extended to include the Mongols; in antiquity, hell was also known as Tartarus. In 1241 Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II wrote he hoped the Mongols would be “driven down to their Tartarus—ad sua Tartara Tartari detrudentur.”

The first column of 20,000 Mongols advanced through southern Poland. On April 9, 1241, they clashed with the coalition of Poles, Moravians, and Knights Templars assembled by Henry II. The battle took place outside the city of Liegnitz (today’s Legnica, in southern Poland).

Organized in raiding parties who communicated with each other by flags and whistling arrows, the Mongols made several feint attacks and false retreats that disoriented Henry’s forces. The attackers also used dense black smoke to confuse the heavy cavalry and leave the infantry undefended. The Mongols scored a key victory at the Battle of Liegnitz. Henry II was killed, and the Mongols hoisted his severed head around on a spear for weeks.

After defeating a European coalition at the Battle of Liegnitz (in modern Poland) in 1241, the Mongol armies paraded around the city with the severed head of the defeated Henry II of Silesia, shown in the 1451 manuscript Freytag’s Hedwig Codex.

WHA/Album

It looked like the next target would be the kingdom of Bohemia. Its king, Wenceslas I, offered last-minute support to his brother-in-law Henry II but had to return to protect Bohemia when he heard about the disastrous defeat at the Battle of Liegnitz. To his surprise, the Mongols didn’t continue their advance westward. After wiping out the Hungarians’ Polish allies, the Mongols turned south to rejoin the main body of the army, which had by then advanced into the heart of Béla IV’s Hungarian kingdom.

Two days after victory at Liegnitz, Batu Khan crushed the Hungarians at the Battle of Mohi (near modern Muhi), decimating European forces. The win, scored on April 11, 1241, used a brutal maneuver called the nerge, a hunting tactic consisting of encircling a large area on horseback and corralling prey into an ever shrinking circle. Once the Hungarian army was contained, Batu Khan’s forces could easily dispatch them.

Hungarian cavalry vainly attempt to repel a Mongol attack on a bridge over the Sajó River at the Battle of Mohi on April 11, 1241, in a miniature from a 13th-century French manuscript.

Album

It’s estimated the Hungarians lost more than 10,000 men (the Mongols allegedly filled nine sacks with severed ears) at Mohi. The Mongols’ superior battle skills at war enabled them to keep annihilating their enemies. Béla managed to escape and, together with his Cuman guard, traveled first to Austria and then south through Croatia, Serbia, and Albania. A Mongol detachment launched after him, but Béla evaded them by hiding on a small island off the Adriatic coast.

(This Austria-Hungarian ‘workaholic’ emperor was hiding a tumultuous private life.)

After Mohi, the Mongols sacked the Hungarian capital, Strigonium (today called Esztergom). Hungarian resistance held out for nine months west of the Danube, but the cold winter caused the river to freeze, allowing the bulk of the Mongol army to cross and ultimately reach Vienna. Then, just when they seemed to have the total conquest within their grasp, the advance halted and the Mongols retreated.

Mongol helmet made of iron strips from the 15-16th century

MMA/RMN-Grand Palais

What caused their sudden retreat in spring 1242 has been a matter of debate. Some sources attributed it to the death of the great khan Ögödei in December 1241. Both Batu Khan and Subutai would have been required to return to Karakorum, Mongolia, to participate in the election of a new leader. Some historians are skeptical that they could have learned of their leader’s death so quickly and point to other reasons, such as the weather. A drastic drop in temperatures and the scarcity of pasture for Mongolian horses could have caused tactical issues for their armies.

Recent archaeological research has revealed that the Mongol army suffered larger numbers of casualties during the Hungarian offensive than previously reported. These heavy losses may have convinced the Mongol generals to retreat to conserve their numbers.

The Golden Horde

Batu Khan did not abandon his conquests in Europe. In southern Russia he established a Mongol state, known as the Golden Horde, on the Cuman steppe. It would expand to rule lands from the Carpathian Mountains in eastern Europe to Siberia. Batu established his capital at Sarai along the lower Volga, although scholars still debate the city’s exact location.

(Kublai Khan did what Genghis could not—conquer China.)

The Golden Horde reached its peak in the early 14th century, when Islam became its official religion. The state collected tribute from peoples across eastern Europe, Asia, and the Middle East and grew wealthy through trade in the Mediterranean. Everything seemed poised for continuous growth until the Black Death struck in 1347.

The plague greatly weakened the Golden Horde’s hold over its dominions. In 1359 civil war erupted and lasted for decades. Eventually, widespread unrest, division of rule, and border disputes undermined Mongol control. The Golden Horde went into decline and local powers slowly regained control, as the last vestiges of the Mongol invasion slowly faded.

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : National Geographic – https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/mongols-empire-conquest-europe