A monthly overview of recent academic research about Wikipedia and other Wikimedia projects, also published as the Wikimedia Research Newsletter.

“How Wikipedia Became the Last Good Place on the Internet” – by reinterpreting NPOV and driving out pro-fringe editors

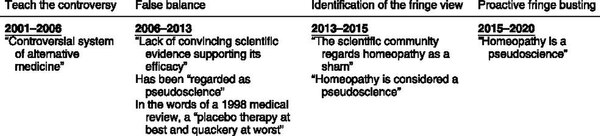

Development of the lead section of the homeopathy article, 2001-2020 (from the paper)

Development of the lead section of the homeopathy article, 2001-2020 (from the paper)

A paper[1] in the American Political Science Review (considered a flagship journal in political science), titled “Rule Ambiguity, Institutional Clashes, and Population Loss: How Wikipedia Became the Last Good Place on the Internet”

[…] shows that the English Wikipedia transformed its content over time through a gradual reinterpretation of its ambiguous Neutral Point of View (NPOV) guideline, the core rule regarding content on Wikipedia. This had meaningful consequences, turning an organization that used to lend credence and false balance to pseudoscience, conspiracy theories, and extremism into a proactive debunker, fact-checker and identifier of fringe discourse. There are several steps to the transformation. First, Wikipedians disputed how to apply the NPOV rule in specific instances in various corners of the encyclopedia. Second, the earliest contentious disputes were resolved against Wikipedians who were more supportive of or lenient toward conspiracy theories, pseudoscience, and conservatism, and in favor of Wikipedians whose understandings of the NPOV guideline were decisively anti-fringe. Third, the resolutions of these disputes enhanced the institutional power of the latter Wikipedians, whereas it led to the demobilization and exit of the pro-fringe Wikipedians. A power imbalance early on deepened over time due to disproportionate exits of demotivated, unsuccessful pro-fringe Wikipedia editors. Fourth, this meant that the remaining Wikipedia editor population, freed from pushback, increasingly interpreted and implemented the NPOV guideline in an anti-fringe manner. This endogenous process led to a gradual but highly consequential reinterpretation of the NPOV guideline throughout the encyclopedia.

The author provides ample empirical evidence supporting this description.

Content changes over time

First, “to document a transformation in Wikipedia’s content,” the study examined 63 articles “on topics that have been linked to pseudoscience, conspiracy theories, extremism, and fringe rhetoric in public discourse”, across different areas (“health, climate, gender, sexuality, race, abortion, religion, politics, international relations, and history”). Their lead sections were coded according to a 5-category scheme “reflect[ing] varying degrees of neutrality”:

“Fringe normalization” (“The fringe position/entity is normalized and legitimized. There is an absence of criticism”)

“Teach the controversy”

“False balance”

“Identification of the fringe view”

“Proactive fringe busting” (“Space is only given to the anti-fringe side whose position is stated as fact in Wikipedia’s own voice”)

The results of these evaluations, tracking changes over time from 2001 to 2020, are detailed in a 110-page supplement, and summarized in the paper itself for nine of the articles (Table 1) – all of which moved over time in the anti-fringe direction (see illustration above for the article homeopathy).

Editor population changes over time

To explain these changes in Wikipedia’s content over the years, the author used a process tracing approach to show

[…] that early outcomes of disputes over rule interpretations in different corners of the encyclopedia demobilized certain types of editors (while mobilizing others) and strengthened certain understandings of Wikipedia’s ambiguous rules (while weakening others). Over time, Wikipedians who supported fringe content departed or were ousted.

Specifically, the author “classif[ied] editors into the Anti-Fringe camp (AF) and the Pro-Fringe camp (PF)”. The AF camp is described as “editors who were anti-conspiracy theories, anti-pseudoscience, and liberal”, whereas the PF camp consists of “Editors who were more supportive of conspiracy theories, pseudoscience, and conservatism.”

To classify editors into these two camps, the paper uses a variety of data sources, including the talk pages of the 63 articles and related discussions on noticeboards such as those about the NPOV and BLP (biographies of living persons) policies, the administrator’s noticeboard, and “lists of editors brought up in arbitration committee rulings.” This article-specific data was augmented by “a sample of referenda where editors are implicitly asked whether they support a pro- or anti-fringe interpretation of the NPOV guideline.”

(Unfortunately, the paper’s replication data does not include this editor-level classification data – in contrast to the content classifications data, which, as mentioned is rather thoroughly documented in the supplementary material. One might suspect IRB concerns, but the author “affirms this research did not involve human subjects” and it was therefore presumably not subject to IRB review.)

“Referenda and Subsequent Exits” (Table 3 in the paper)

“Referenda and Subsequent Exits” (Table 3 in the paper)

Tracking the contribution histories of these editors, the paper finds

The key piece of evidence is that PF members disappear over time in the wake of losses, both voluntarily and involuntarily. PF members are those who vote affirmatively for policies that normalize or lend credence to fringe viewpoints, who edit such content into articles, and who vote to defend fellow members of PF when there are debates as to whether they engaged in wrongdoing. Members of AF do the

opposite.

The paper states that pro-fringe editors resorted to three choices: “fight back”, “withdraw” and “acquiesce” (similar to the Exit, Voice, and Loyalty framework).

The mechanism underlying these changes

The author hypothesizes that

The causal mechanism for the gradual disappearance is that early losses demotivated members from PF or led to their sanctioning, whereas members of AF were empowered by early victories. As exits

of PF members mount across the encyclopedia, the community increasingly adopts AF’s viewpoints as the way that the NPOV guideline should be understood.

To support this interpretation, the paper presents a more qualitative analysis of the English Wikipedia’s trajectory over time:

“Step 1: Rule Ambiguity” of the NPOV policy, which initially “allowed for inclusion of lower-quality sources, so long as they were attributed”

“Step 2: Clashes between Camps over Rule Interpretations”

“Step 3: Formation of a Power Asymmetry”

“Over the course of years, AF successfully shaped how to understand the practical application of Wikipedia’s NPOV guideline. These early victories gave AF an upper hand in editing disputes …” Here, the author highlights the role of ArbCom: “Two particularly important early arbitration rulings in the early years were the arbitration committee cases on climate change (2005) and pseudoscience (2006), which largely reaffirmed some viewpoints held by AF in those specific disputes and led to sanctions that primarily targeted prolific PF editors […]”

“Step 4: Reinterpretation of Wikipedia’s Rules”. Here, the author details various aspects, e.g.

an increased ability of “experienced editors […] to drive disruptive ‘newcomers’ away from Wikipedia and instill in newcomers’ certain understandings of how rules should be interpreted.” Also

Also, “the gradual development of a sourcing hierarchy—whereby some sources were deemed reliable, and others were deemed unreliable—created advantages for AF editors.” The 2017 ban of the Daily Mail is highlighted as a milestone, followed by deprecations of various other sources (Table 2).

“How Did the NPOV Rule Change” (figure 2 from the paper)

“How Did the NPOV Rule Change” (figure 2 from the paper)

The author also discusses and rejects various alternative explanations for “why content on the English Wikipedia transformed drastically over time.” For example, he argues that while “Donald Trump’s 2016 election, the 2016 Brexit referendum, and the emergence of ‘fake news’ websites” around that time may have impacted Wikipedia editors’ stances, this would not explain the more gradual changes over two decades that the paper identifies.

Fringe and politics

As readers might have noticed above, the author includes political coordinates in his conception of “fringe” (“more supportive of conspiracy theories, pseudoscience, and conservatism”) and “anti-fringe” (“anti-conspiracy theories, anti-pseudoscience, and liberal”). This is introduced rather casually in the paper without much justification. (It also puts the finding of a general move towards “anti-fringe” somewhat into contrast with some older research by Greenstein and Zhu. They had concluded back in 2012 that the bias of Wikipedia’s articles about US politics was moving from left to right, although this effect was mainly driven by creation of new articles with a pro-Republican bias. In a later paper, the same authors confirmed that on an individual level, “most articles change only mildly from their initial slant.”[2])

Even if one takes into account that the present paper was published in the American Political Science Review, and accepts that in the current US political environment, support for conspiracy theories and pseudoscience might be much more prevalent on the right, that would still raise the question how much these results generalize to other countries, time periods or language Wikipedias – or indeed topics of English Wikipedia that are less prominent in American culture wars.

Indeed, in the “Conclusion” section where the author argues that his Wikipedia-based results “can plausibly help to explain institutional change in other contexts”, he himself brings up several examples where the political coordinates are reversed and the “anti-fringe” side that gradually gains dominance is situated further to the right. These include the US Republican Party in itself, where “Trump critics [i.e. the “pro-Fringe” side in this context] have opted to retire rather than use their position to steer the movement in a direction that they find more palatable”, and “illiberal regimes within the European Union have gradually been strengthened as dissatisfied citizens migrate from authoritarian states to liberal states.”

As these examples show, the consolidation mechanism described by the paper may not be an unambiguously good thing, regardless of one’s political views. For Wikipedians, this raises the question of how to balance these dynamics with important values such as inclusivity and openness. But also, the paper reminds one that inclusivity and openness are not unambiguously beneficial either, by demonstrating how by reducing these in some aspects, the English Wikipedia succeeded in becoming the “last good place on the internet.”

See also a short presentation about this paper at this year’s Wikimania (where Benjamin Mako Hill called it a “great example of how political scientists are increasingly learning from us [Wikipedia]”)

Briefly

See the page of the monthly Wikimedia Research Showcase for videos and slides of past presentations.

Other recent publications

Other recent publications that could not be covered in time for this issue include the items listed below. Contributions, whether reviewing or summarizing newly published research, are always welcome.

“It’s not an encyclopedia, it’s a market of agendas: Decentralized agenda networks between Wikipedia and global news media from 2015 to 2020”

From the abstract:[5]

“This paper presents a media biography of Wikipedia’s data that focuses on the interpretative flexibility of Wikipedia and digital knowledge between the years 2001 and 2022. [….] Through an eclectic corpus of project websites, new articles, press releases, and blogs, I demonstrate the unexpected ways the online encyclopedia has permeated throughout digital culture over the past twenty years through projects like the Citizendium, Everipedia, Google Search and AI software. As a result of this analysis, I explain how this array of meanings and materials constitutes the Wikipedia imaginaire: a collective activity of sociotechnical development that is fundamental to understanding the ideological and utopian meaning of knowledge with digital culture.”

References

^ Steinsson, Sverrir (2023-03-09). “Rule Ambiguity, Institutional Clashes, and Population Loss: How Wikipedia Became the Last Good Place on the Internet”. American Political Science Review: 1–17. doi:10.1017/S0003055423000138. ISSN 0003-0554.

^ Greenstein, Shane; Zhu, Feng (2016-08-09). “Open Content, Linus’ Law, and Neutral Point of View”. Information SystemsResearch. doi:10.1287/isre.2016.0643. ISSN 1047-7047. ![]() Author’s copy

Author’s copy

^ Ren, Ruqin; Xu, Jian (2023-01-28). “It’s not an encyclopedia, it’s a market of agendas: Decentralized agenda networks between Wikipedia and global news media from 2015 to 2020”. New Media & Society: 146144482211496. doi:10.1177/14614448221149641. ISSN 1461-4448.

^ Zheng, Lei (Nico); Mai, Feng; Yan, Bei; Nickerson, Jeffrey V. (2023-07-03). “Stigmergy in Open Collaboration: An Empirical Investigation Based on Wikipedia”. Journal of Management Information Systems. 40 (3): 983–1008. doi:10.1080/07421222.2023.2229119. ISSN 0742-1222.

^ Jankowski, Steve (2023-08-12). “The Wikipedia imaginaire: a new media history beyond Wikipedia.org (2001–2022)”. Internet Histories: 1–21. doi:10.1080/24701475.2023.2246261. ISSN 2470-1475.

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : Hacker News – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Wikipedia_Signpost/2023-11-06/Recent_research