![]()

ABOUT CALIE

MISSION STATEMENT

EVENTS BOARD

NATIVE NEWS

Publishing Corner:

ROY COOK NEWS BLOG

THE INDIAN REPORTER

TRIBAL BLOGGERS

Indian Community:

TRIBAL COMMUNITY

PROFILES

SOARING EAGLES

Science & Wonder

ASTRONOMY PORTAL

KID’S CLUBHOUSE

Indian Heros:

VETERAN COMMUNITY

MEDALS OF HONOR

CODE TALKERS

FAMOUS CHIEFS

HISTORIC BATTLES

POEMS ESSAYS

SPORTS-ATHLETES

MISSION FEDERATION

FAMOUS INDIANS

California Indian Art:

MISSION BASKETS

RED CLAY POTTERY

ETHNOGRAPHIC ART

CAVE ART

MUSIC

CALIE Library:

FEDERAL Resources

HEALTH & MEDICAL

INDIAN BOOK LIST

HISTORICAL Documents

CALIF ED DIRECTORY

Academic Financial Aid:

SCHOLARSHIPS

GRANTS & FUNDING

Tribal Governments:

TRIBAL COURTS

SOVEREIGNTY

SOCIAL SERVICES

TRIBAL DIRECTORY

Indian Gaming:

INDIAN CASINO FORUM

JOBS BOARD

CONTACT CALIE

LINKS

SITE MENU

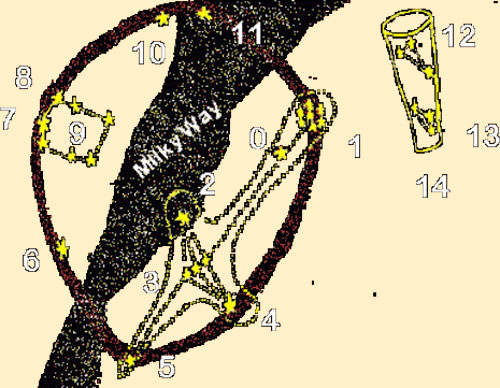

NATIVE AMERICAN INDIAN Stars Charts

by Roy Cook, Opata-Oodham, Mazopiye Wishasha: Writer, Singer, Speaker

Summer is a great time to look to the stars. Many times at night, when the air is still in the desert or we are on a high place elsewhere, it seems we can almost touch the stars. Some say all that we need to know is in the sky above us if we just take the time to SEE and not just look. Sacred Above, X , Sacred, Below. How many stars are there in the sky? How many stories about the stars are there? There are many Tribal stories that explain and/or include the stars. We will look to four tribal stories: from the West, East, South and North.

Where I am from, Southern Arizona, these things are best done in sets of four. Traditionally the Oodham watch the stars and when the Pleiades cross the sky in one night that is the proper time for story telling. These nights are the longest of the year. The stories are told for four nights. Traditionally by groups of two, one telling the story and one assisting him. There is an often-told Tohono O’odham story that describes the Milky Way as spilled tepary beans a coyote stole and dropped as he ran away.

Some stories can only be properly told at night or in certain seasons. To do otherwise would be telling stories in the offseason and that would jeopardize the supply and growth of plants. To do so would be offensive to the roots of the upright people and the root people would go away and never come back. We have always respected those roots. Look to the sky and we will start with the Southern California region we are in now, Ipai-Tipai, Kumeyaay land.

Cinon Duro (Hokoyel Mutaweer), Mesa Grande Ipai, years ago said: In the beginning, there was no form or shape. The Sky-Power Father and Earth Mother, Sinyohauch, gave issue to two sons: Tuchaipa, the first born, and Yokomatis, the younger. The brothers created man, the sun, the moon, and the stars. First, they sent the sky up by blowing tobacco into the air. The Creator, Tuchaipa, made hills and valleys, which had low places for water to pond up. He took mud from the ground and made the first man and first woman. The Indians were made first, then other people. The people walked to the east in darkness until he made light for them. Tuchaipa was poisoned by a frog, who was angry that he was made so ugly and that people were laughing at him. During the time he was dying, he taught people about their world. When he died, he departed through Pamu (in the mountain foothills of San Diego near Ramona) to San Diego Bay, went along the beach, and then into the water where he disappeared. As he stepped through the countryside, his footprints left impressions on the mountains and rocks. When he was thirsty, he marked a bowl-shaped area in a rock, and this filled with water. He left these marks, which are still there today, so that his children would see evidence that the Creator had been there and had traveled from the mountains to the ocean.

Diegueño ground paintings as including the native universe, including the sun, new and old moons, and celestial objects as well as landmarks, such as Santa Catalina Island, the Coronado Islands, San Bernardino Mountain, and the Cuyamaca peaks. Also observed in a ground painting is a rock in the ocean (Coronado Islands), Viejas Mountain, San Jacinto Mountain, a mountain east of Picacho Mountain, and other nearby locations. Depending on the village, different landmarks are shown in the painting, indicating highly localized and varied perceptions of the native landscape. All, however, include the ocean. The origin stories involve emergence from the ocean; one of the twins (see above) was blinded by the salt water.

Ground Painting, made by Manuel Lachuso, an old man of Santa Ysabel. He had forgotten the precise location of the milky way, sun, new moon, and old moon, so they are omitted. He made no mention of toloache mortars.

1.—Atoloi, witch mountain on an island, identified by the informant with Coronado Island.

2.—Nyapukxaua, mountain where people were created.

3.—Wikaiyai, San Bernardino mountain.

4.—Axatu, Santa Catalina island.

5.—Awi-, rattlesnake.

6.—Etcekurlk, wolf.

7.—Xatca, Pleiades.

8.—Namul, bear.

9.—Nyimatai, panther.

10.—”Cross star”.

11.—Sair, buzzard star.

12.—Xawitai, grass or blue garter snake.

13.—Xilkai-r, red racer snake.

14.—Awiyuk, gopher snake.

15.—Watun, “shooting” constellation.

16.—Amu, mountain-sheep, three stars of Orion.

17.—Spitting hole, diameter about 8 inches.

18.—Horizon, forming the visible limits of the earth.

Also documented is this Ground Painting made by Antonio Maces and Jo Waters, old men at Mesa Grande.:

1, 2, 3.—Kalmo and witu-rt, toloache mortar and pestle.

4, 5.—Awi-, rattlesnake.

6.—Xatatku-rl, milky way.

7.—Amut kwaptcurpai, world’s edge.

There is some doubt as to the correct color for this figure.

8.—Halyaxai, new moon.

9.—Halya, full moon.

10.—Inyau, sun.

11.—Hatapa, coyote.

12.—Sai-r, buzzard star.

13.—Crow.

14.—Halturt, black spider.

15.—Katckurlk, wolf.

16.—Amu, mountain-sheep, Orion.

17.—Hatca, Pleiades.

18.—Awi–ni-l, black snake.

19.—Awl-yuk, gopher snake.

20-23.—Mountains.

Recently noted by ‘Jr’ Cuero: The social, and cultural significance of this ground painting for a geographical territory predating the beginning of the Late Period is linked with the existence of a cycle of songs that describe the same circle boundary. According to Harry Paul Cuero, Jr., speaker Tipai and traditional singer, the circle corresponds with both creation narratives and a major cycle of traditional songs they called the Lightning Songs (possibly the songs of Chaup, a supernatural being associated with ball-lightning and who travels above the ground (Waterman: 342)). Paul Cuero, Jr. knows two Elders who sing the Lightning Songs. He has himself on occasion helped out in their singing. The Lightning Songs record the social and cultural relationships with Tribes on the other side of the Ipai-Tipai circle/boundary, such as the Mojave, Cocopa, and Cahuilla.

Harry Paul Cuero, Jr. said that the Lightning Songs describe geographical locations as seen from the perspective of the air, beginning in the northeastern desert area (to the right of the San Bernadino Mountains), and moving south, following the circle boundary. He recalled that one site the songs described was the well-known tidal plume near Ensenada, Mexico.

Other coastal locations are mentioned, including Catalina Island. The songs also describe social interactions with different groups. Unnamed tribes living on the other side of the northern boundary are described in the songs, and the Cahuilla are mentioned as living near to the San Bernardino Mountains. Describing various kinds of interactions with the Cahuilla, the songs’ descriptions ultimately return to the northeastern desert area where they began, describing relationships with other desert Tribes near the former Lake Cahuilla. Luiseno groups are not mentioned in the Lightning Songs, and both San Jacinto and San Bernadino Mountain are north of present-day Luiseno territory.

The first songs in the Lightning cycle are in the Mojave language, then in Cocopa, and finally in the Tipai language. Other song cycles describe how the Mojave and Cocopa nations were placed on earth at the time of creation, and their social and cultural relationship to one another: the Mojave are younger than the Cocopa, and both are younger than the Tipai.

The Tipai are culturally mature and responsible for instructing the other Tribes in ceremonial practices given to the Tipai at the area called Guatay, in English “Big House” in Pine Valley, near Viejas and El Captain Reservations.

When the world was new, there were few stars in the sky and corn was the staple of the Cherokee people. One morning, an elderly couple discovered that a giant spirit dog has been eating their cornmeal during the night. The next time he appears, the people jump out from hiding, beating drums and shaking rattles, and chase the dog into the sky. As he flies away, cornmeal drops from his mouth and becomes the stars of the Milky Way, called Gil’liutsun stanun’yi, or “the place where the dog ran” in Cherokee.

Lakota star knowledge legends: Big Dipper, Orion’s Belt, Seven Council Fires, Fallen Star, Lakota constellations winter sky mythology, Devil’s Tower, Harney Peak, magpie, Greek’s Betelgeuse Pleiades buffalo in the stars, Black Hills legend and Lakota astronomy

The Lakota constellations are visible in the winter sky, and they reflect Lakota mythology. A notable aspect of that mythology is that every event and object on earth has a correspondent in the sky.

To the Lakota, the stars of the Big Dipper signify the Seven Council Fires. One story tells of a Lakota woman who went to the sky to marry a star, then fell to her death from a rope of braided timsila ‘turnip’ stems as she was trying to return to her village on earth through a hole in the constellation. Even as she died, her child was born, and Fallen Star became the hero of many Lakota myths associated with the stars.

There is a star grouping in the southern sky. It depicts a brother and sister who climbed a low hill at Fallen Star’s urging to avoid a pursuing bear. Fallen Star (a voice of power) made the hill rise, taking the children out of reach of the bear, who clawed futilely up and down its sides. The scoring from its claws can still be seen in what is called today as Devil’s Tower in Wyoming.

Another story recorded in the stars is the story of Wicincala Sakowin (seven girls) camped near what is now called Harney Peak. Over seven days, each was taken off to the sky by an eagle. Fallen Star defeated the bird and returned the girls to earth but left their spirits in the sky.

In the Lakota star field, Tayamnicankhu (Orion’s Belt) is the spine of a bison. The Tayamnitucuhu is the bison rib structure (Greek’s Betelgeuse and Rigel) in that constellation. The six-star cluster Pleiades in what the Greeks saw as the constellation Taurus, is the bison’s head and Tayamnisinte (Sirius) is the tail.

Those stars and others low on the winter sky also depict Ki Inyanka Ocanku (a racetrack) surrounding He Sapa (the Black Hills.) Black Hills is the heart of everything that is. On this racetrack course, all the birds and animals raced four times around the Black Hills. The winner would decide if humans would remain on earth or would be swept away by the Thunder Beings.

The race was won by a bird, the long-tailed, black-and-white magpie, a creature viewed as only slightly better than a pest species by most people today. It should be held in higher regard; the magpie decided that humans could stay. Its great gift to mankind is memorialized in Lakota astronomy.

You might keep that in mind, if you are at ceremony and the Thunder Beings drop in for a visit!

Back to the CALIE Space Portal.

![]()

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : Hacker News – https://www.californiaindianeducation.org/science_lab/indian_stars.html