PAX Unplugged 2023 —

Tabletop is bigger than ever. What’s it like trying to get your game out there?

Kevin Purdy

– Dec 23, 2023 1:00 pm UTC

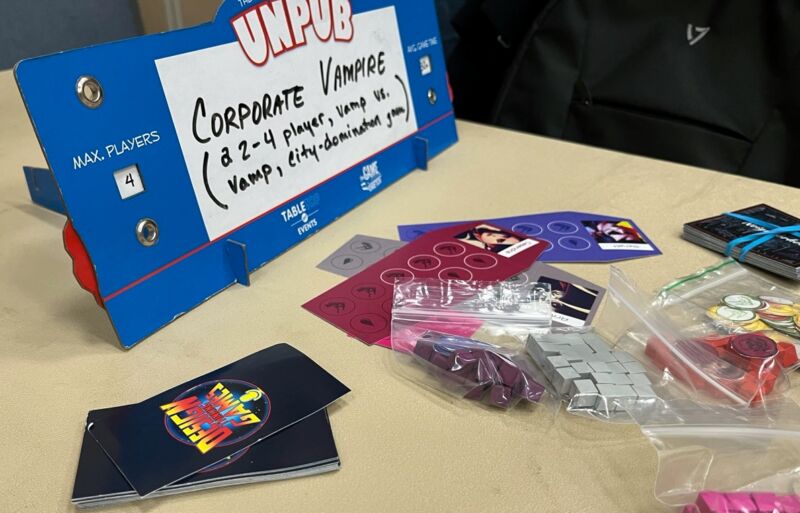

Enlarge / Given only this sign, and a glimpse of some pieces, a constant stream of playtesters stopped by to check out what was then called Corporate Vampire.

Kevin Purdy

“You don’t want Frenzy. Frenzy is a bad thing. It might seem like it’s good, but trust me, you want to have a blood supply. Frenzy leads to Consequences.”

It’s mid-afternoon in early December in downtown Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Convention Center, and I’m in the Unpub room at PAX Unplugged. Michael Schofield and Tim Broadwater of Design Thinking Games have booked one of the dozens of long card tables to show their game Corporate Vampire to anybody who wants to try it. Broadwater is running the game and explaining the big concepts while Schofield takes notes. Their hope is that after six revisions and 12 smaller iterations, their game is past the point where someone can break it. But they have to test that disheartening possibility in public.

I didn’t expect to spend so much of my first PAX Unplugged hanging around indie game makers. But with the tabletop industry expanding after some massive boom years, some Stranger Things and Critical Role infusions, and, of course, new COVID-borne habits, it felt like a field that was both more open to outsiders than before and also very crowded. I wanted to see what this thing, so big it barely fit inside a massive conference center, felt like at the smaller tables, to those still navigating their way into the industry.

Here are a few stories of parties venturing out on their own, developing their character as they go.

How much vampire influence is too much?

Corporate Vampire (or “CorpVamp”) has been in the works since summer 2022. The name came from an earlier, more Masquerade-ish idea of the game, in which you could take over a city council, build blood banks, and wield political influence. But testing at last year’s Unplugged, and the creators’ own instincts, gradually revealed a truth. “People really like eating other people,” Schofield says.

Along with input from game designer Connor Wake, the team arrived at their new direction: “More preying, more powers that make players feel like mist-morphing badasses, more Salem’s Lot, less The Vampire Lestat.”

By the end of the weekend, they’ll have taken up a playtester’s naming suggestion: Thirst. But for now, the signs all say CorpVamp, and the test game is a mixture of stock and free-use art, thick cardboard tiles, thin paper tokens, glossy card decks, generic colored wooden cubes, and a bunch of concepts for players to track—perhaps too many.

Hand-cut tokens and make-do squares for an early version of Thirst.

Kevin Purdy

The way CorpVamp/Thirst should go is that each night, a vampire wakes up, loses a little blood, then sets out to get much more back by exploring a Victorian city. In populated neighborhoods, a vampire can feast on people—but doing so generates a board-altering Consequence, such as roving security guards or citizens discovering bodies. Vampires accumulate victims and hypnotize them for Influence, depending on who the victims are (“Judge” versus “Roustabout,” for example), turn them into “Baby Vampires,” or simply keep them as blood stock. You win by accruing victory points for various misdeeds and achievements.

One player, who told the designers that a different game’s play-test saw him “break the game in 10 minutes,” seemed bothered by how Consequences can be triggered by a single player’s actions but affect all players. Another has a hard time keeping track of the tokens for influence, movement, and blood, and when to move them on and off the board. That’s called “mess testing,” Schofield tells me, and he’s working on it. Some things will be easier to learn and use when the pieces have better designs and materials. But the CorpVamp team can’t jump to that stage until the mechanics are locked down.

As that group finishes a test, another group sits down immediately, having stood nearby to ensure their chance. Schofield and Broadwater won’t lack for players in their three-hour slot. That tells the team there’s “evidence of a market,” that their game has “stopping power” and “shelf value,” despite its obscurity, Schofield says. But there’s lots of work still to be done in alpha. “The costs of powers are too high, the powers aren’t badass enough [emphasis his], and the tactile movement of placing cubes and flipping tokens isn’t quite right,” he later tells me.

After more iterations and some “blind” play tests (players learning, playing, and finishing the game without creator guidance), the game will be in beta, and the team will get closer to pinning down the look and feel of the game with illustrators and designers. Since their schedules only afford them roughly three hours of dedicated collaboration time every week, they lean on what they’ve learned from their product-oriented day jobs. “Frequent iterations and small feedback loops will iron things out,” Schofield says. “Process wins.”

Then they can “enjoy the problems of production and distribution logistics.” After that, “We’ll sell copies of Thirst at the next PAX Unplugged.”

Kevin Purdy

“Don’t do miniatures for your first version”

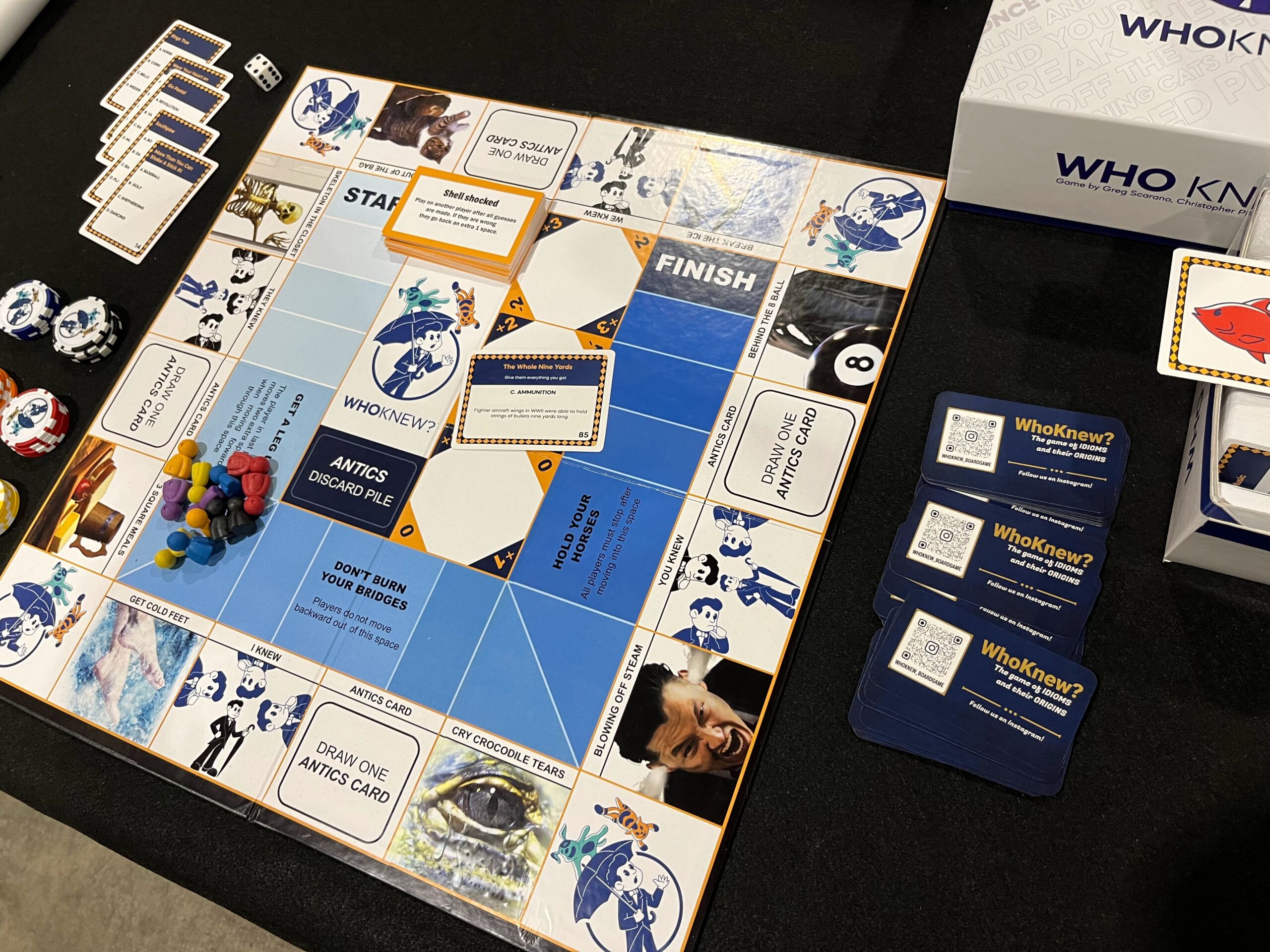

I played a few different games at PAX Unplugged that were at various stages before publication. One called WhoKnew? was on its second year at the conference. The first year was simply designer Nicholas Eife tagging along at a friend’s booth, bringing only a piece of paper and asking people who wandered by if they thought a trivia game based on the origins of idioms would work. This year, there was an actual table and a vinyl sign, with an early-stage board and trivia cards laid out.

I drew the phrase “The whole nine yards” and I chose “British Artillery” as its origin. Eife congratulated me (The length of a Vickers machine gun’s ammo belt as the origin of the phrase is far from a solved matter, but I will not concede my point.) I asked the designer what state the game will be in next year. “I guess we’ll have to see,” he said, displaying the slight grin of a person working entirely within their own timeline on a purely passion-driven project. It was almost uncomfortable, this calm, patient demeanor amidst the murmuring chaos of the show floor.

An Indie Game Alliance member demonstrates “Outrun the Bear” at the IGA booth at PAX Unplugged 2023

Indie Game Alliance

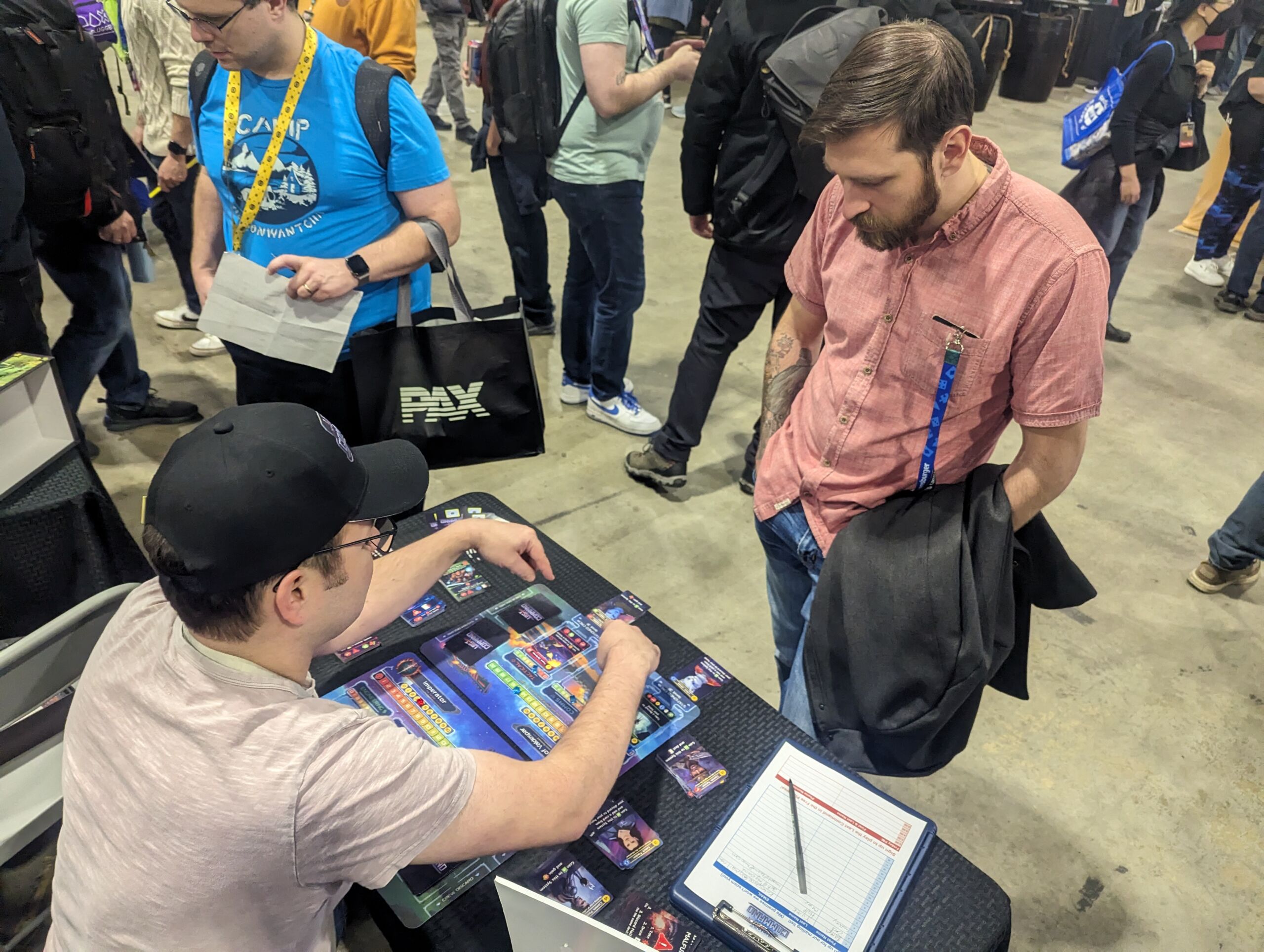

Perhaps looking for a less idyllic counterpoint, I asked Matt Holden, executive director of the Indie Game Alliance, what it’s typically like for new game makers. For a monthly fee, the Alliance provides game makers with tools typically reserved for big publisher deals. That includes international teams for demonstrating your game, co-op-style discounts on production and other costs, connections to freelancers and other designers, and, crucially, consulting and support on crowdfunding and game design.

Holden and his wife Victoria have been running the Alliance for more than 10 years, almost entirely by themselves. At any given time, the Alliance’s 1,800-plus current and former members have 30-40 Kickstarters or other crowdfunding campaigns going. Crowdfunding is all but essential for most indie game makers, providing them working capital, feedback, and word-of-mouth marketing at the same time. Holden can offer a lot of advice on any given campaign but has only one universal rule.

“Don’t make miniatures for your first version of your game, no matter how big your campaign is getting. Just don’t do it,” Holden said, then paused for a moment. “Unless you worked for a company that made miniatures, and you’re an expert on them, then go ahead. But,” he emphasized, “miniatures are where everyone gets stuck.”

Has the burgeoning interest in tabletop and role-playing changed how indie games get made, pitched, and sold? Holden thinks not. The victories and mistakes he sees from game makers are still the same. Games with unique and quirky angles might have more of a chance now, he said, but finding an audience is still a combination of hard work, networking, product design, and, of course, some luck.

An IGA member demonstrates Last Command at PAX Unplugged 2023

“I can’t tell somebody what’s going to guarantee their [crowfunding] campaign works. Nobody can,” Holden said. “But you do enough of them, and you see the things that the campaigns that work, and those that don’t, have in common.”

Patience would seem to be one of them. As I sat talking to Holden at the Alliance’s booth, game demo volunteers gently interrupted to ask for advice or the whereabouts of some item for their table. Putting in the time at conventions, game stores, and friends’ tables, testing and demonstrating, is critical, Holden said, and it’s a big part of what the Alliance helps newcomers coordinate.

I later traded emails with Eife of WhoKnew (a title that also seems to be in flux). He was eager to tell me that, after two weeks of conventions, including PAX Unplugged, the feedback and enthusiasm “gave us that boost of confidence and the desire to push.” So he and his team “put our nose to the grindstone and immediately started making corrections and changes.”

I realized, at some point over that weekend, that I’d been holding onto an idea about board game success that was dated, if not outright simplistic. I’d held out the story of Klaus Teuber’s four years developing Settlers of Catan as the paradigm. He had worked, reportedly unhappily, as a dental technician, tinkering with the game in his basement on nights and weekends, dragging new copies upstairs every so often for his family and friends to test. One day, it was successful enough he could quit messing with people’s teeth.

There were, I would find out, a lot of paths into developing a modern tabletop experience.

Cassi Mothwin, working the +1EXP booth at PAX Unplugged 2023

Cassi Mothwin

Page: 1 2 Next →

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : Ars Technica – https://arstechnica.com/?p=1992547