In the summer, Ubisoft released its first-ever ‘Canadian Impact Report’ to celebrate 25 years in the country.

The French gaming giant opened its inaugural Canadian studio in Montreal in April 1997, and Canada has been a big part of its business ever since. In fact, many of the company’s most popular franchises, including Assassin’s Creed, Far Cry, Rainbow Six, Splinter Cell and Prince of Persia, have been primarily developed at Ubisoft Montreal. With over 4,000 employees, it’s easily Ubisoft’s largest studio in the world.

It’s a distinction that isn’t lost on Chadi Lebbos, Ubisoft Montreal’s vice president of production.

“I’ve been at [Ubisoft] Montreal since the beginning — I was [one of] the first 40 employees. So I’ve seen the studio evolve, the studio change and the talents and expertise growing,” he says. “We started by shipping Playmobil games and we’re now doing Rainbow Six Siege, Assassin’s [Creed], Far Cry, etc. So yeah, we have come a long way. It’s been a fun, rocky road, let’s say — it’s really, really intense.”

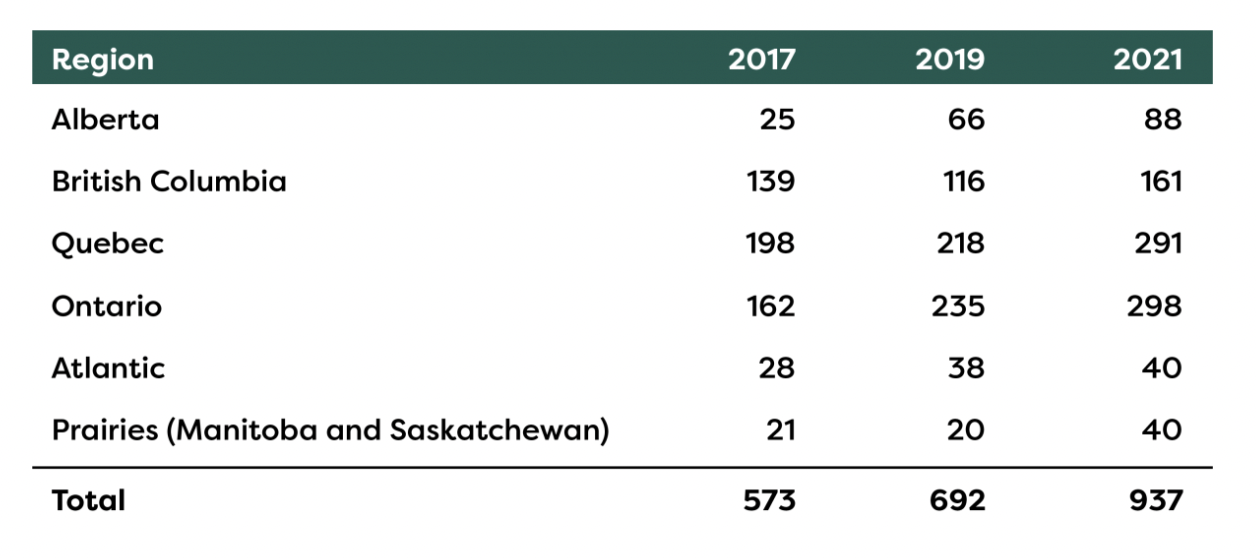

The breakdown of video game studios by province in 2021. Image credit: Entertainment Software Association of Canada

Today, Canada is the third-largest producer of games in the world, which is quite an achievement given our country’s size. Over $5.5 billion of Canada’s annual GDP comes from the national games sector and its roughly 1,000 studios. Of course, it wasn’t always that way.

“What’s interesting is that was kind of when video games were starting to become mature as an industry, even the first little bit. So we really followed that,” says Leslie Quinton, Ubisoft Montreal’s vice president of talent and vice president of communications.

“And as the studio has grown, now we have a whole campus — it used to be just one floor in this building. So I think it’s been a really interesting journey in that sense to kind of follow the different evolutions — the fact that now 49 percent of players are women and that the whole model has shifted so much. And we’ve been part of that growth all the way through.”

Lebbos adds that in 1997, the Montreal game development scene wasn’t anywhere near as saturated as it is today. “When we came into Montreal, there was [Dead by Daylight developer] Behaviour, and then there was us, and suddenly, the Montreal gaming scene started to really take its place.” Now, he notes, there are big names like Eidos Montreal (Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy), Warner Bros. Montreal (Gotham Knights) and EA Motive (this year’s Dead Space remake).

Ubisoft Montreal. Image credit: Flickr — Shuichi Aizawa

“It’s exploded all over. And it’s fun to see that because there’s a huge pool of talent within Montreal — within Canada, basically. And that comes from both the passion for games — for passion, for creativity, for arts, for culture — that is really present there, but also the fact that there are awesome universities that are doing amazing work in providing these talents.”

Part of that includes Ubisoft’s two motion-capture studios being located in Montreal and Toronto. This means that even games that aren’t being primarily made in Canada, like the Swedish team Ubisoft Massive’s Star Wars: Outlaws, still leverage the Canadian mo-cap technology. In particular, the star of the game is Venezuelan-Canadian actress Humberly González, while the narrative team is located at Ubisoft Toronto.

Even a comparatively smaller-scale Ubisoft title, like the just-released Assassin’s Creed Mirage, saw 13 studios in total contribute, including lead developer Ubisoft Bordeaux and the Montreal studio. Lebbos says it took a while to work up to these massive global undertakings, but they’re made possible thanks to a process called “distributed development” that involves “a lot of communication” and “clear mandates in order to be able to give autonomy” to each collaborator.

It’s also efficient in situations where one studio might have specialities that others can lean on. “If you have a game where you need to have animal companions, there are some studios that excel in that. So that part of the mandate will be carved out, ‘Here’s our needs, here’s the brief, here’s what we require.’ And then they’ll come back and say, ‘Here’s how you animate a dog, here’s an animated lizard’ or whatever.”

Ubisoft Montreal’s Far Cry 5 is one of several Ubisoft games featuring animal companions. Image credit: Ubisoft

Revealing more about the kind of work that goes into game development, as well as the people responsible for it, is what spurred the release of the Impact Report.

“A lot of the people who work here are equally gamers, as well as producers of games,” says Quinton. “And we wanted people to understand that all the social preoccupations of the rest of the world are present here as well, and that the cool thing is we actually have the tools to do something about them — that we can normalize certain behaviours in games, for example, that will lead to more green behaviour, or show more diversity.”

A big part of that, she says, is education.

“Games are such an important way of outreach. Because first of all, it’s the old statistic: one in three people around the world play games. So in other words, we’re already in your pocket in your home. And why would we not think about using that as a positive tool for reinforcing the kinds of behaviour and thinking that will contribute towards a more positive future?”

This includes teaching material in the likes of the free-to-play Rabbids Coding and premium Assassin’s Creed games, the latter of which offer modes like ‘Discovery Tour’ to let players learn more about historical settings. Discovery Tour is also sold separately from the games and is even available for use in schools for free as part of Ubisoft’s ongoing partnerships with universities and other institutions.

Discovery Tour for Ubisoft Montreal’s Assassin’s Creed Valhalla lets players explore historical Norway and England to learn more about Viking and Anglo-Saxon perspectives. Image credit: Ubisoft

“The idea is that it’s an interactive way of teaching history and making it relevant in a way that just reading it from a book doesn’t necessarily provoke because you can picture it yourself. So it has this amazing power of recreating this third space where people can both interact within an environment to really end up learning and with other people around them to create community,” she says. “That’s the other key component of games today, of course — the notion of the communities you create and the socialization. So learning through socialization, through fun, innovative ways — every teacher everywhere has always looked for new and interesting ways to reach their students, and games are such an important tool for that.”

She adds that the United Nations has even identified video games as one of the primary tools for social change. “That’s what they’re using to reach refugees — that’s what they’re using to reach various communities about social change and the environment.” It’s a far cry from the debates that surfaced around the time Ubisoft Montreal first opened about the so-called “dangers” of games. Lebbos also points out that something like Ubisoft Montreal’s Assassin’s Creed Unity can help preserve pieces of history like Notre Dame.

On a broader level, Quinton hopes that the Impact Report can dispel the perception that “people in gaming companies are always behind their screens.” She notes that developers enjoy being out in the community to clean riverbeds and parks, deliver food and more.

“There is such a commitment to not just being passive, which is something I really love about the gaming community. It really busts the myth, that kind of stereotype of the person who’s antisocial,” she says. “We are involved with art. We have a partnership here in Montreal with an organization that uses our building to display art for free. We have artists and residents whom we support. There are just no limits.”

Lebbos says many people also start in other fields, like law, and want to break into the gaming industry, and Ubisoft has initiatives — which will be communicated publicly in the future — to support that. The idea is that in the years since Ubisoft started in Canada, there’s now so much potential — and interest — in making games.

“Technology has been democratized by many external companies [like] Apple, and this has also helped the games to be democratized as a really a social medium, where it’s like TikTok, it’s like Instagram, it’s your grandma playing on her phone. We have all these genres coming together around one medium that is the video game industry.”

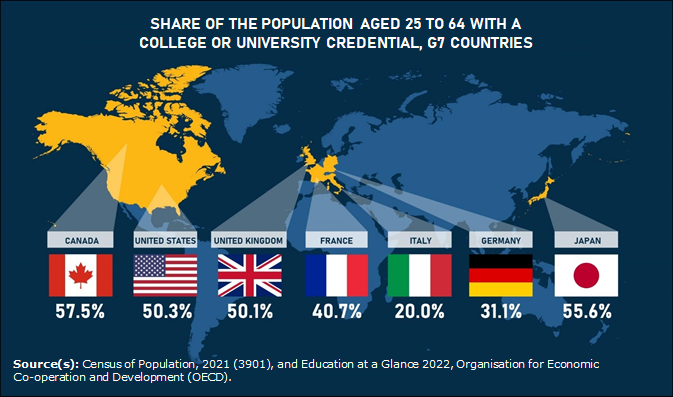

Of course, the Impact Report also helps illustrate the size and talent of Canada’s gaming industry. Part of that comes down to lucrative tax incentives in Quebec and other provinces, but Quinton believes it boils down to Canada itself being significantly educated and creative.

“I would say across Canada, maybe particularly in Montreal, there’s a high level of creativity,” she says, citing everything from Cirque du Soleil and the Toronto International Film Festival to the Moment Factory and Ubisoft’s own Montreal-based Hollywood production VFX team, Hybride.

“This is an environment that breeds an interesting blend of those two things that need to come together for games: the creative side and the technology side. So that is a particular advantage that we have in Canada. There’s a lot of great art in every sense in Canada and when you bring that together with the high-level education — technology — it’s the perfect recipe for for games to flourish.”

“This is an environment that breeds an interesting blend of those two things that need to come together for games: the creative side and the technology side. So that is a particular advantage that we have in Canada. There’s a lot of great art in every sense in Canada and when you bring that together with the high-level education — technology — it’s the perfect recipe for for games to flourish.”

“And for the number of companies which we also work with that are way more on the culture aspect, we do brainstorm sessions just to be able to push their ideas so everything is gelled together. And even if we come from different backgrounds, the medium, which is the art — it could be the game, it could be a video, it could be a VR experience — it’s what really unites us,” adds Lebbos.

“We kind of punch above our weight, Canada, if you think about our population, in terms of our involvement in those kinds of high-level entertainment things. So the idea is that we definitely have this capacity in Canada. Maybe we’re too ‘Canadian modest,’” Quinton muses with a laugh. “We’re too humble!”

Image credit: Ubisoft

>>> Read full article>>>

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source : MobileSyrup – https://mobilesyrup.com/2023/10/17/ubisoft-vice-president-interview-25-years-in-canada/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=ubisoft-vice-president-interview-25-years-in-canada